Around this time every year, as the weather warms and the burden of spring classes starts to take its toll, the bougie and largely complacent population of my small liberal arts college finds a socially charged catalyst to ignite a campus-wide discussion on “uncomfortable” topics. Don’t take my tone as disparaging – often times, these conversations have promoted crucial, interesting and eye-opening revelations, strengthening our student body as a whole as we learn more about each other, our commonalities and our differences. This year, however, the catalyst and the ensuing debate left much to be desired: after hiring Chance the Rapper for our spring concert, a controversy flared over his use of the word “faggot” in one of his more widely known hits (“Favorite Song”). Again, this isn’t to dismiss the concerns and anxieties of the student body – the college has an obligation to respond to cultural currents and its not unreasonable to expect our entertainment committee to pick a performer that appropriately embodies our mutually shared political and social attitudes. But at the end of the day, as I absorbed the dialogue and reflected on the situation, I couldn’t help feel like it all boiled down to a largely privileged set of undergraduates trying to tell a rapper what he could and could not say.

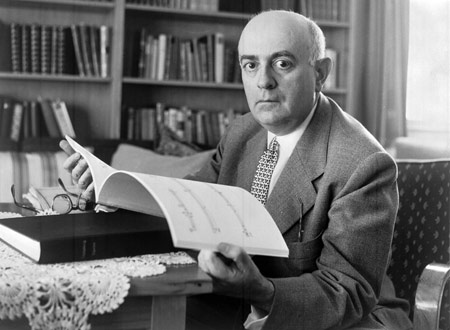

Rap is often pretty confrontational in nature. The lyrics confront us, the beat confronts us, and if the rapper’s anyone worth listening to, the flow and energy confront us, too. This is what excites me so much about my favorite rappers, and it’s where I feel, despite the enormous historical, cultural and intellectual chasm, that the musical philosophy of Theodor Adorno manifests in the contemporary era. Adorno is one of the pillars of “critical theory”, that esoteric branch of political philosophy that seeks to redeem and revitalize Marxism for modern times (namely, after the failure of the communist project in Russia). Adorno’s body of work is enormous and his intellectual contributions to the Western canon are profound. But he interests me most for his work dedicated to music. Adorno styled himself a sort of philosophical music critic, and sought to understand the music of his era (early 20th century art music) in terms of its reflection on society, on the brutality of bourgeoisie domination (it’s Marxism, remember) and the ways music can awaken and shape society. For Adorno, powerful atonal music, full of dissonance and uncomfortable moments, could awaken its audience to the brutality and contradictions of the world around them. Such music was said to have a critical stance towards society. In other words, harmony and consonance, those beloved tools of Bach and Mozart, were bourgeoisie trifles. Dissonance and discord are the weapons of a Marxist utopia.

Unfortunately, and unsurprisingly, he limited this analysis to the music of privileged bourgeoisie white men, composers like Schoenberg and his disciples. He reviled “light” music, the sort of tunes one would hear on the radio – this music was according to Adorno “illusory”, and served only to mask the ways in which capitalism dominates our lives. Famously, and perhaps tragically, he had a special hatred for Jazz. Jazz, he argued, pretended to have a critical stance, but was too rigid in form and predictability to actually function the way Schoenberg’s music did. Critics of Adorno have responded to his revulsion of jazz in a number of ways. Some argue he was too immersed in classical music to take jazz on its own terms. Others contend what he meant by jazz was that dweeby, awful knock-off music early century Germans thought was jazz (cf. the operetta “Johnny’s Jazz Band” for a real bizarre treat). And of course, there’s always that racial issue as well. But whatever his motivations, Adorno missed out big: jazz can be (and often is) as critical as the most discordant, ear-shattering atonal works. And so, I argue, can hip-hop, especially the music being made today by rising and established stars such as Danny Brown, Schoolboy Q, Kendrick Lamar, Killer Mike – even Ab Soul on a good day. Adorno would probably have reacted with shock and abhorrence at the sound of this music. But, just as with jazz, he would have missed the big picture.

Rap music is primed to reveal the contradictions of capitalist domination and unveil the myriad of ways in which we oppress one another, even though it involves lyrics. Adorno felt that vocal music faced an uphill battle to be critical because it was too representational: in order for music to reveal the contradictions of capitalism, he argued, it had to deny all representational semblance, and be the sonic equivalent of abstraction for the visual arts. Vocal music is by default expressive and representational, so how can it fulfill this criteria? The lyrics of rap however are more than merely representational. The medium is relevant: they’re not singing or talking, they’re rapping, a method of musical delivery than over the recent decades has confirmed in its subject matter an intimate, personal quality that does more than deliver words – rap delivers the truth of structural conditions and the forces that have shaped the rapper’s own life. A soprano singing an aria does her best to imbue the libretto with as much musical and personal expressive force as she can, but when Danny Brown delivers a verse he’s sending out the essence of Danny Brown. He’s not just representing, he’s presenting, and what’s he’s presenting are the structural forces and societal limits that left him to deal drugs, fight thugs on the way to buy groceries and yearn to escape his home town.

Adorno says that critical music jars the listener: an audience to an atonal string quartet yearns for pleasing consonances, the II-V-I resolutions of tonal harmony, but they get only unresolved dissonance. This tension, Adorno claims, awakens them to the ways in which bourgeoisie domination creates contradictions and brutal, unresolved societal dissonances. Underground (and increasingly, mainstream) rap often has the same function: you might want to hear about love, friendship, concord and all the other pleasing consequences of bourgeoisie indulgence. But Schoolboy Q shows you a perverted notion of what wealth and luxury are, outside the typical middle class framework. Ab Soul challenges the authoritative forces we take for granted around us constantly (if you can take him seriously, which I recommend at least trying). Danny Brown reminds us, in the age when hip hop artists insist on rapping about their cars, jewels and women, the bleakness and hopelessness he barely escaped to be on a stage (check out “Fields” and “Scrap or Die” for the most raw, revolutionary tracks on his acclaimed album XXX). And Chance the Rapper in “Favorite Song” reminds us of the societal conditions than tolerate and often condone homophobic, ultra-masculine attitudes. Middleclass bourgeoisie audience may not like any of this – but that’s the damn point. We live in a society rife with contradictions, and we need music that constantly reminds us that these contradictions exist and aren’t improving anytime soon, especially if we refuse to let those on the lesser end of these contradictions tell us about their lives themselves, no matter what words they use.

So would Adorno get down to Bruiser Brigade and dip to “Druggies wit Hoes”? Definitely not – the great irony of his work is the privilege he accords to the bourgeoisie intellectual tradition at the expense of the cultures and aesthetics he sought to redeem through Marxism. But that’s okay: his message resonates across the decades, down into the grungy underground clubs where my favorite rappers got their starts. Rap music shouldn’t be about you hearing what you want to hear, what affirms your comfortable existence. It’s about other people’s voices, other people’s experiences, manifested hopefully in the grimiest, dirtiest, most musically exciting ways. Does this mean when the proletariat finally seizes the means of production, they’ll be blasting not Schoenberg’s atonal opera but “Collard Greens”? I wouldn’t be mad. ▩