The Marsh Girl and the Sexy Men of Where the Crawdads Sing

The blockbuster book and film tapped grand Southern themes—and cashed in on a post-feminist fantasy

Where the Crawdads Sing | By Delia Owens | G.P. Putman’s Sons, 2018 —> Where the Crawdads Sing | Directed by Olivia Newman | Hello Sunshine, 3000 Pictures, 2022

Where the Crawdads Sing hit cinemas in summer 2022, earning a mighty $137 million at the global box office, matching the commercial success of the novel (with over 15 million copies sold to date), and proving the world has an insatiable appetite for the whodunnit-thriller-romance-drama. While Crawdads may be generically confused, book and film share the same narrative beats, and attempt to tap grand themes of prejudice and alienation in the mid-century U.S. South.

They tell the story of Kya Clark, the “marsh girl” of Barkley Cove, whose once proud, slave-rich family fell into poverty in the North Carolinian swamps. As each member of the family peels away, Kya is left to fend for herself and build a life set in defiance against society at large. Though both versions position Kya as fiercely individualistic and liberated from the norms of mainstream society, they lumber unwittingly into worn concepts of what it means to be a woman. Fascinated with nature and equipped with rudimentary survival skills, Kya claws her way into adulthood only to be torn between two archetypal men: Tate Walker, sensitive son of a local fisherman, and the brash, stud athlete Chase Andrews.

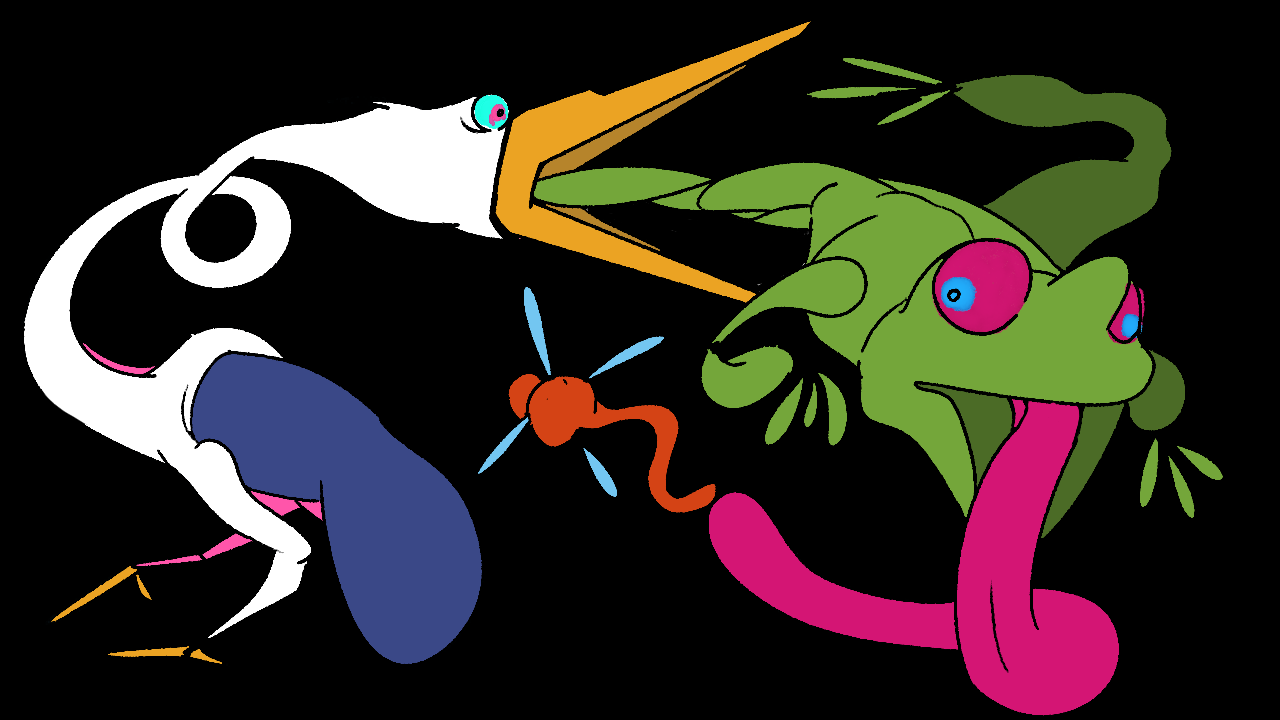

Delia Owens’ novel flits between parallel narratives. The first takes place in the “present” of 1969, when Chase, Barkley Cove’s star quarterback, has been murdered under mysterious circumstances that suggest Kya is the killer. The second takes place during Kya’s childhood and explores the pain of her mother’s abandonment, the freedom associated with the death of her abusive father, and her reliance on animals and plant-life for sustenance and concealment from the outside world. Alone in a shack far from the nearest town, Kya walks barefoot through her swamp, hides from strangers in the brush, and builds an impressive collection of specimens and drawings of local wildlife.

The novel frames its human dramas within a wild and natural milieu. Throughout, we’re treated to poetic and scientific descriptions—smoldering dawns, hunkering bullfrogs, skies swirled with sycamore leaves alongside talk of genus, bone wear, and mating rituals—all of which charge Kya’s world with charm and wonder. A self-proclaimed “tangle-haired, barefoot mussel-monger,” she barters or hunts for most of her food, and only participates in the world of laws, ownership, and capital when compelled by others. In rejecting the consumer society operating a few miles up the coast in Barkley Cove, Kya cultivates a bountiful existence on her own terms, free from the quotidian concerns of school or the 9-5 working life. And yet, eyeing the meager means and basic living conditions that bring her freedom and joy, the cove’s white inhabitants see her as less, a subordinate social Other. They indulge in prejudice for prejudice’s sake, calling her “swamp trash” and feeling justified in doing so.

Like Harper Lee’s To Kill A Mockingbird, Crawdads operates from the perspective of a young female protagonist in the South living in an overtly racist society, and leads up to an all-deciding court case. Yet, despite clear resonance between Kya’s low social status and the civil rights struggles that characterized the time and place, the book never seriously looks at how race shapes the setting. Kya associates with the Black bait shop owner Jumpin’ and his wife Mabel out of necessity, trading fishing catch for essentials likes gas and grits. Yet the marsh girl and the Black occupants of the cove find no common cause. Whatever possibilities for racial solidarity lie latent here, Owens never draws them out to useful effect. Instead, the latter half of the novel focuses on Kya falling for and obsessing over Chase and Tate, the young white men of the cove and brood of the very people who despise her.

Olivia Newman’s film adaptation of Where the Crawdads Sing bundles the entirety of the novel’s 1969 segments—in which local police investigate Chase’s murder—into the first ten minutes of screentime. The story only begins once Kya (Daisy Edgar-Jones) is put on trial, narrating her life story in voiceover from her jail cell.

From the beginning, the film is mired in an over-polished aesthetic, its soft-toned cinematography suggesting a comfortable, rosy and unimpeachable past, scrubbed of the civil rights struggle that defined it. The aesthetic extends to the characters: note the perpetual, laundry-ad cleanliness of Kya, for example, a girl who lives alone in a swamp. With a frock for every occasion, her outfits evoke an Abercrombie summer catalogue, whitewashing her poverty and life outside of civilization, and meshing awkwardly with the novel’s lightly anti-consumerist themes.

The animals and plants that inject some measure of vitality into the book are afforded precious little screentime. Though Kya sketches the wetland wildlife around her, we sense no true listening or seeing. Instead, she lives for men—Tate and Chase (Taylor John Smith and Harris Dickinson), giving over to them her time, attention, and body. Rare is the shot in the middle 70 minutes of the film where Kya is not seen gazing longingly at or daydreaming about one of them. By spending less time studying the plants and animals that enrichen Kya’s world, the film reduces the story to a pairing of romance and courtroom drama clichés.

Much like the novel, the film plainly echoes aspects of To Kill A Mockingbird. But bare-faced gambits, like the visual reference to Robert Mulligan’s 1962 film adaptation when Kya’s lawyer Tom Milton (David Strathairn) grandstands in an Atticus Finch-evoking white suit, don’t land. Such allusions align Kya with Mockingbird‘s Tom Robinson, a Black man falsely accused and on trial for rape. While the presumption of the accused’s innocence that comes part and parcel with this parallel is a sly misdirection on Newman’s part, it nonetheless feels tasteless to use the vocabulary of popular cinema to conflate Kya’s murder trial with a touchstone civil rights tale.

To the film’s credit, Jumpin’ (Sterling Macer Jr.) and Mabel (Michael Hyatt) transcend the characters of Owens’ novel, which depicts them as infantilised and subservient. Macer Jr’s performance in particular confers intelligence and grit, disguised but not absorbed by the deferential qualities of the character Owens wrote.

Both versions of Crawdads position their protagonist at odds with the conventions of the period setting. But the conceit is hard to take seriously. The independent female protagonist, who has grown up on the fringes of society, is beset by a regressive naïveté and all-consuming desire for young men.

This characterization parallels other contemporary female-led films and books, like the Twilight and Fifty Shades series, continuing a post-feminist trend in popular media which portrays feminism as having been “achieved” while blithely embracing dated gender stereotypes. Novel and film alike waste their shared premise, trading the potential for a story in which an outcast woman seizes control of her own existence and rallies against baseless prejudice, for a story about an obsession with young white men.

Crawdads doesn’t interrogate desire; it rolls over and accepts it. Fiercely independent, Kya has grown up away from mid-century gender stereotypes, where women are expected to be submissive, dependent, and easily influenced. Yet, for the majority of both film and novel, when not immersed in studies of plants and animals, she is crippled by an oscillating desire for Tate and Chase, succumbing to an outdated notion that single women must be consumed by the want of male attention. Somehow, free from society’s influence, Kya conforms to the aforementioned stereotypes and more, as if it’s a woman’s essential nature to crave pretty dresses and make-up, and to swoon over headstrong young men who offer them boats, picnics, and tumbles in the long grass.

The drift into Twilight and Fifty Shades territory demonstrates a cynical desire to land the same demographic, but why so many are compelled towards long-term fixations on vacuous stories is merely a matter of repetition. Audiences have been primed for these texts by a barrage of media over the past 30 years deploying seemingly feminist premises as window-dressing for retrograde stories. It’s an aesthetic of subversion, but it bolsters the status quo. ▩