The Arab World’s New, Dubious YouTube Radicals

In the last decade, the revolutionary energy of millions has been extinguished—replaced by a new, pseudo-revolutionary form of political engagement.

E

very August 14th, veterans of the Arab uprisings remember the Raa’ba Al-Adawiya massacre, which took place in a suburb of Cairo in 2013. Raa’ba Square had been a protest zone for more than six weeks, recalling Tahrir Square in January, 2011. In Raa’ba, the supporters of President Mohamed Morsi, most of whom were Muslim Brotherhood members but also other Egyptians hailing mostly from the outskirts of Cairo and impoverished parts of the country, called for restoring “legitimacy.” This meant reversing the coup d’état which the General Abdel Fattah el-Sisi led the previous July, with support from mostly well-off Egyptians and liberals. That August 14th, law enforcement under el-Sisi swept in to clear the camps, and in the process killed at least 800 people.

The unrest had begun in Tunisia, where protests in 2011 felled a dictator, emboldening Egyptians who believed the regime of Hosni Mubarak favored the rich and left the poor behind. These protests fragmented the capitalist class, a minority of whom wanted Mubarak’s son Alaa to inherit his father’s post. Mubarek could not survive the division of the ruling class; he had to leave after 18 days, and a military council assumed control over Egypt. In June 2012, a candidate for the Muslim Brotherhood, Mohamed Morsi, was sworn in as a democratically elected president.

He didn’t last long. Much of the public felt Morsi, committed to the Brotherhood, failed to rule on behalf of all Egyptians. Spurred by the military, a movement called tamared—sedition—insisted on the immediate termination of Morsi’s tenure. Though the tamared movement emerged from a genuinely popular coalition, it was seized on by reactionary forces who wanted to restore the old order. Those reactionary forces invested in el-Sisi, who was Morsi’s defense minister. With the coup, el-Sisi defeated the Brotherhood, and he proceeded to silence members of the anti-Morsi coalition who had made it possible for him to mount his coup in the first place. el-Sisi’s support now comes mostly from the two rich Gulf sheikdoms, Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates.

The Muslim Brotherhood played a confusing role in these processes. It did not support the revolution until it was clear that Mubarek would soon be ousted. And amid much of the turmoil, the Brotherhood remained cautious, lest it anger the military. Yet after the Raa’ba Al-Adawiya massacre, el-Sisi outlawed the Brotherhood, squashing his political rival. In the wake of anonymous attacks on police stations, el-Sisi classified the Brotherhood as a terrorist entity, and effectively froze all its activities, whether political or not.

Following the coup, el-Sisi put the position of President on hold—an insignificant official, Adli Mansour, was momentarily put as head of state—and a year later el-Sisi won a sham presidential election. The ceremony of his swearing-in took place in the renovated palace of the last and deposed king, before the Free Officers’ revolution of 1952. That ceremony has been el-Sisi’s way of telegraphing a restoration—recalling the restorations of 1848—a desperate attempt to roll back time to the good old days of the monarchy, when commoners did not dare challenge their social betters.

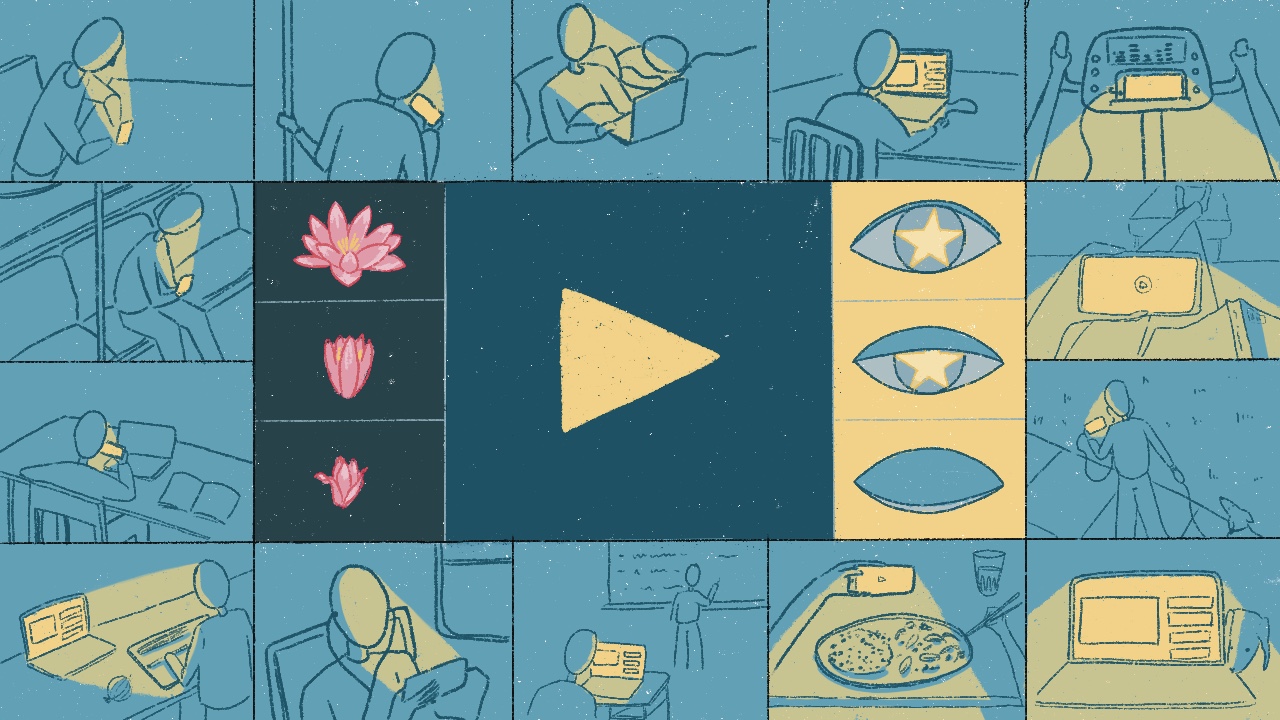

In the last ten years, the revolutionary energy of millions has been extinguished. It has been replaced by a new, pseudo-revolutionary form of political engagement. Every night, potential revolutionaries watch their preferred opposition leader, who happens to be a content creator and a media guru, as he or she scathingly criticizes the regime, points out its many deficient policies, and foretells its imminent collapse.

Thusly, a vast pool of potential demonstrators has turned into passive viewers of “revolutionary” TV and YouTube channels. A population of active revolutionaries who could alter reality in favor of the revolution has become a set of depressive audiences in virtual space. Their perceived obligation to keep abreast of the scandalous pitfalls of the regime is satisfied by “analysis.” Online activists count millions of views on social media platforms and TV stations. But they are not likely to foster true revolutionary ardor anytime soon.

Political shows are not a new phenomenon in the Arab world. But with the eruption of the uprisings in 2011, they become more popular, drawing millions of viewers each night. Indeed, calls for demonstrations could not have been possible without internet democratization. And after el-Sisi’s coup, nightly or weekly shows transmitted by Egyptians from their Turkish exile emerged as a vital breath of fresh air.

Yet to collapse physical space through internet and satellite broadcasting is not a viable long-term political strategy. Given the restrictive conditions established by the coup, politically active populations cannot tolerate indefinitely a political opposition that mobilizes from the safety of exile. Calls for action yielded no action. They resulted instead in inebriated audiences.

Primetime, breathtaking shows on stations like Mekameleen TV and Elsharq TV expose the poor performance and endemic corruption of el-Sisi’s government. From one’s spot on a cozy sofa, and armed with either a remote control or a Samsung phone, the politically conscious, and what has been left of the democracy militant, thinks he has mastered the world by taking his daily or weekly dose of pseudo-revolutionary content. Passively, that viewer feels empowered, witnessing the exposure of scandal after scandal.

The shows peddle ramblings and ruminations about the el-Sisi regime, mistaking the coverage for the hard stuff that might actually bring it down, and create the conditions for an egalitarian order. With the militant on the sofa, the vomits and excrements become perverse entertainment, without which he or she cannot confront the next day or week. In what used to be the revolutionary camp, one finds audience who have adopted the characteristics of the post-truth world with surprising nonchalance, as they entertain the lie, in the daily or weekly spectacles, that el-Sisi’s fall is imminent.

Consider one show, With Moataz, hosted by the former sports journalist Moataz Matar on the Elsharq TV station. Before Matar’s eviction from his Turkish exile to London in early 2022, the show ran five days a week and almost two hours each night. The show presented as investigative journalism, with leaks and exclusive reporting from “reliable sources inside the regime,” and Matar has become a celebrity all over the Arab world for his fiery introductions, famously always ending with the adage Allah Ghalib: “God is victorious.”

Besides detailing the dysfunctions of the Egyptian regime, the show trades on the genre of wailing, a weeping style of (mostly) poetry in Muslim Shiite theology that evokes the painful memory of the killing of Prophet Muhammed’s grandson, Hussein. While neither Matar does not literally cry, nor are audiences are not solicited to literally cry, all are nevertheless invited to loath in self-pity. With time, audiences start deriving a pathological satisfaction from their own inertia before the incumbent counterrevolutionary orders. Revolution-as-entertainment places these audiences in the camp of the rightful. But when rightfulness reverses into an identity taken for granted, one loses sight of what it is to constantly see and act on what rightfulness means and demands. Viewers finish the show with loads of pathos, but little ethos or logos.

The whole oppositional endeavor results in the massive emergence of passive and ahistorical freaks, devoid of substance and vitality. The closing phrase which has secured Matar’s fame, “God is victorious,” is precisely a call for passivity. Since God is all knowledgeable and powerful, the defeatist reasoning goes, why bother putting one’s life on the line by mounting a revolution?

The content of such TV and YouTube shows is indeed incendiary. On October 3rd, 2022, on the show Officially el-Sisi Offers Egyptians for Sale, Matar claimed that the regime officially acknowledged the existence of a market for collecting body parts, and selling them to rich clients from the Gulf. By founding the biggest center for transplanting body parts in the Middle East, el-Sisi, according to Matar, institutionalized what used to be a black market.

Similarly, on Oct. 4th, 2022, on a show titled Defecting Intelligence Officer: Uprisings Began My Income Increased and Missions Changed, a defected officer recounted how his superiors in the notorious Algerian secret intelligence charged him with following the hirak activists, famous for the popular uprisings in 2019. The former officer recounted the extra-judicial regulations by which intelligence disappeared activists, such that there existed no chance for loved ones to learn their whereabouts.

Amid such startling reports, those who were meant to be influenced by that militant substance, and carry out the revolutionary work, instead begin to assume that the fall of such a monstrous el-Sisi’s regime must be a matter of time alone. They start assuming that the military regime is rapidly disintegrating and cannot survive the stream of scandals exposed every night. Everyone fantasizes about the impending fall of the regime, but no one dares to assume the steering wheel of the revolution, since it has been imagined to be already unfolding, miraculously, all by itself.

Over the last ten years, the fiery content meted out each night has enforced the false omnipresent. Even when it is subversive, as political opposition, revolutainment, as I call it, is not only non-revolutionary but dialectically counterrevolutionary.

Ask the content creators and “celebrity revolutionaries” of YouTube what it is, exactly, they desire. When squarely pushed for an answer, which of the two choices is the dearest to their hearts? The downfall of el-Sisi’s regime as they profess they want to see—a situation that can only come with the end of their gold-mine businesses in political opposition—or the infinite perpetuation of the current situation?

Their heart favors the latter option. Celebrity Algerian oppositionists can generate from YouTube something between $1,500 to $2,000 per night. With certain Egyptian oppositionists-entertainers, the sum is easily three or four times that figure. The farcical state of affairs recalls a telling scene in Fyodor Dostoyevsky’s Brothers Karamazov. Jesus Christ makes a second coming and freely engages in healing work, whereupon the Grand Inquisitor ushers Jesus into the prison. Jesus meets this fate because his message stands at odds with—and has literally interrupted the mediating and corruptive work of—the church. Likewise, in the event of the fall of the military regime in Egypt and elsewhere in the Arab world, celebrity YouTubers and career oppositionists will become personas non grata; their entertaining content will no longer have an audience because the work needed, that of consciousness-raising, will be over. For career oppositionists, true emancipation of their respected polities spells the gravest disaster.

| YouTuber | Subscribers | Other remarks | Links to check the evidence |

| Moataz Matar | 3.88 m (since 2010)11m on Facebook | Known before in Elsharq TV | https://www.youtube.com/user/ma7atetmasr/about |

| Mohammed Naser | 900 K (since 2018) | Known before in Mekameleen TV (1.89 m since 2016) | |

| Abdullah El Sharif | 4.3 m (since 2008) | Sarcasticweekly episodes | https://www.youtube.com/c/abdullahelshrif/about |

| Yousef Hussein (known as Joe Show) | 3.48m (since 2015) | Sarcastic weekly episodes | https://www.youtube.com/c/JoeShowAlaraby/about |

| Mohamed Larbi Zitout | 892 k (since 2018) | Daily scandals, analysis. | https://www.youtube.com/c/MohamedLarbiZitoute/about |

| Amir Boukgors (known as Amir DZ) | 1.31 m | Daily Scandals | https://www.youtube.com/c/AMIRDZBOUKHORS |

The present enforcement of the counterrevolution is not, of course, a fault of strategy on the part of the oppositionists and media gurus, or a conspiratorial infiltration that directly sells out to the regime. Rather, oppositional media coverage and exposure of the regime’s many scandals—recently the frantic style has cited the lustful practices of key regime figures—operate in what the philosopher Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel described as the Law of Necessity. Sure, if the agents of the Egyptian regime put their hands on any of the opposition journalists, they will send those oppositionists behind the sun. But the propulsion of both regime and revolutainment nonetheless lead to the same outcome: Both have succeeded in obliterating the materiality of the revolution—the first, through its iron hand and repressive approach; the latter by marketing the illusion of the revolution’s imminent ignition.

To test the commensurability of the oppositionist-entertainers’ work with the counterrevolutionary project, recall that, even when living standards have routinely worsened from those under the late President Mubarak’s era, Egyptians have not marched to the streets or descended to squares. Poverty has reached unprecedented levels and Egyptian public debts are ascendant. el-Sisi’s regime might be diplomatically isolated and financially weak, but it is nevertheless vicious in its dealings with ordinary Egyptians.

Amid the farce of the el-Sisi regime, why no social explosion? Here enters revolutainment, blinding its audiences into the ways history is made. Consider Hegel’s “Knowledge of the Absolute,” through which ordinary people, not intellectuals or vanguard leaders, decide when and where to jumpstart a revolution. According to Hegel, world-shaking events such as uprisings are neither kicked off through a constitutive assembly, nor by mobilization, nor are they repressed through repression. No amount of repression alone can repel people from deciding their fate. Likewise, no amount of top-down mobilization alone is going to convince people to take to the streets.

Absolute knowledge underlines a people’s collective will—which often remains obscure, for observers and even the people themselves—to jump into history, reverse enslavement, and mount a revolution. It is a collective crossing from a passive threshold of consciousness to an active one, whereupon a historical subject registers his or her permanent movement toward emancipation. Acquiring the certitude of oneself is the understanding that one’s singularity finds its explanation only in the historical motion in which one becomes one with the world, a universal subject, irrespective of geography, language, religion, or culture. Revolution is nothing but the individual’s return to origins, to a desalinated ontological state. When risking their lives in actively anticipating the desalinated world, true revolutionaries cannot help but experience joy. They do not know any of the dejection or fear that fundamentally marks the entertainment-oriented revolutionaries we have been decrying. Revolutainment impairs that necessary threshold of consciousness. It actively impedes that emancipatory return.

Revolutainment, contrary to revolution, thrives on monetization through YouTube viewers. The animating principle of both opposition and regime is a fetish we have all accorded the name of “money”—or surplus value. Instead of serving humanity’s need for exchange, the cumulative effects of surplus value and debt on a global scale have started assuming a life of their own, independent of humanity’s actual needs. When the alleged revolutionary camp and the counterrevolutionary party both fetishize money, independently of the means of accumulating that surplus value, one must then be deranged to expect their basic interests to diverge.

Through their pseudo-thinking, proponents of revolutainment dupe their audiences into thinking that the problem with lies with el-Sisi, his mismanagement, or military background. The real enemy cannot be el-Sisi, the military, or the remnants of the Mubarak regime. The real enemy is not even the capitalists, with their repressive or regressive outlooks, religious or otherwise. The real enemy is money. Until a new moneyless order emerges through workers’ strikes and major organizing, money will keep the world, not just Egypt or the Arab World, estranged from true emancipation. With everyone accessing basic necessities according to their needs, not according to their hours at work, the realm of quantity will be abolished and that of quality will emerge. This is not a futile objective. There are solid historical antecedents, such as the Paris Commune in 1871, Barcelona in 1836-37, and northeastern Syria from 2012-2018.

Forces of revolutainment never broach, let alone engage with, this radical understanding of how the counterrevolution must unfold. The images of piles of dead bodies bulldozered like city rabbles in Ra’baa are available on YouTube, still haunting collective memories. Can we think of double murder, one by soldiers shooting physical bullets, bulldozers turning those bodies into minced meat, the other allegorical as pretentious media renders these sacrifices against tyranny into naught? ▩