A sunglassed man sings and bobs to Chinese pop music. A breeze ripples through his tie-dyed tiger t-shirt, swaying his grey sweatpants. The leaves behind him shake.

Disembodied hands dice a dill pickle, then dip it in chocolate and apply a light white drizzle. The treat is gifted to a child, who bites enthusiastically before twisting her face up in disgust.

A golfer dangles a piece of food above an alligator’s snout. Tick Tock, the cartoon crocodile from Peter Pan, flutters up from the water. The alligator snaps and the man pulls his arm back. Text: He still has his hand!

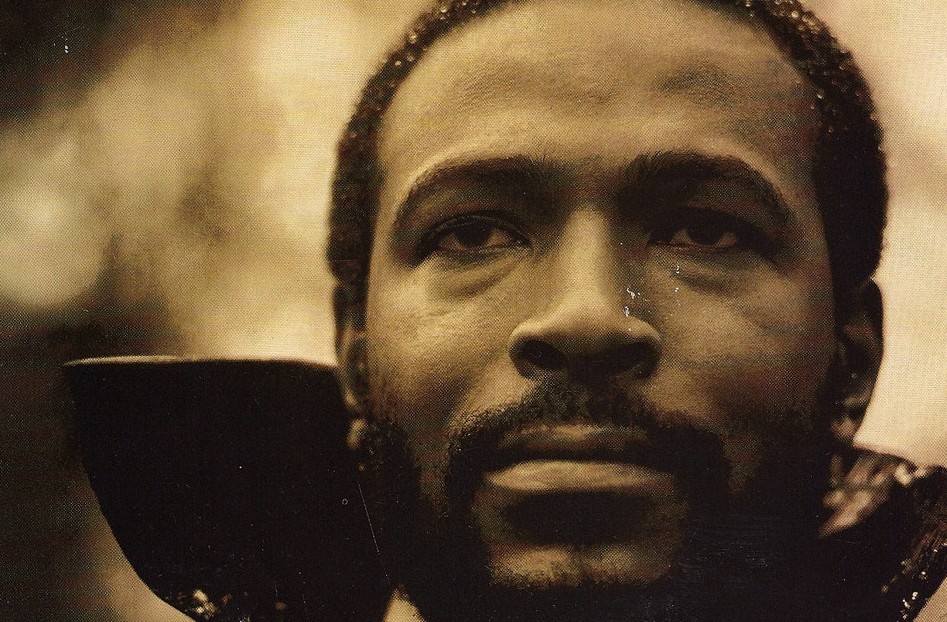

I look up from my phone, and then back again, where another video has already begun: A baby’s sleeping face is pushed into itself (I dizzy) and is revealed to be silicone. I swipe for something else, for something sane, but can only find nonsense, hours and hours of nonsense, and before I can pull my headphones out to think another thought, the room tilts and I heave against my standing desk, my body staggering among the straight lines of the white office space.

I am at work, I remember. It is my job to keep watching. As of yesterday, I am a member of the content team at the next big thing in short-form video, and I must understand what exactly it is that we do.

Ten of us began working at The Startup on the same day late in May, 2019. A table with name tag supplies greeted us, as did donuts and bagels and blank notebooks ordered in from Amazon Basics. More established employees, identifiable by the temerity with which they reached for the snacks, mingled among themselves as us newbies searched awkwardly for direction.

I chatted with a few interns recruited from the nearby business college, as well as a couple of MBA students who had taken the train in from San Francisco. All of them talked about our upcoming summer with such enthusiasm. They wanted to be here and they wanted to stay, badly.

The recruiter waved us to our stations, each marked with a single red balloon printed with The Startup’s logo. Mine was upstairs, on the back wall farthest from the ping pong table. As I approached my new team, I received glances but no greetings. Headphones stayed on. My desk—electrically adjustable and tabula-rasa white—welcomed me with a branded Pop-Socket and a wide-angle lens made to enhance my smartphone camera. A sheet of printer paper ordered my specific onboarding tasks—how to login into email, Slack, the back-end of the app.

I had the sense of being expected and then immediately subsumed. Tropical house music thumped forth from the background. Laptop keys clicked. Already, at 10 A.M., everyone’s eyes looked glazed over. I opened my computer and pretended that I already knew what I was doing, that I had important work to do.

When I interviewed for this job, I was balancing two service gigs in my hometown, living with my parents one year into post-college life. My cousin, who does marketing for The Startup, recommended me to her recruiter as someone who was interested in online video.

I sent out my resume and we organized a call on Zoom, which the recruiter missed on account being busy with more important matters. We rescheduled twice before finally connecting. As we talked, I scribbled notes in my sketchbook, tallying the number of times she mentioned the words “creative” and “content.” She stated, earnestly, that our aim was to addict users to our app.

“Our goal is to be the next $10 billion Snapchat,” the recruiter said, “and if you like social, and you love short video, then you’ll love working here.” My actual job duties remained ambiguous throughout the call. It seemed that my tasks would include working fast and being creative, tracking trends, coming up with ideas for videos, and then sending those ideas out (To whom? To where? What sort of ideas? It was never clear.)

As we said goodbye, the recruiter told me that she’d soon put me in touch with the head of the content team for a second interview. The call ended before I could decide whether or not that was something that I actually wanted.

My second interview was with a woman named Qingling. I Googled her before the call, and discovered that she had previously worked for a media company in China. Now, she headed the content team at The Startup. For our chat, she wore a black hat that read #CreativeAF and thick-rimmed glasses.

We talked about my video experience and I tried my best to sound interested and knowledgeable about The Startup’s work. I observed the deficiencies of TikTok and how The Startup’s app would redress them. I offered ideas for short-video series, talked about how they could make use of some of The Startup’s proprietary technologies, and cited some videos that I had already enjoyed.

In truth, using the app felt akin to riding the bow of a ship through a media storm. Most of the native content felt slipshod, and most of what was good was stolen from other platforms, where it looked better anyway. In preparation for the interview, I was never able to endure more than five minutes of The Startup’s endless video feed, which offered few navigational queues and even fewer points of audiovisual reprieve.

These opinions made me feel at once aged-out and superior, cynical in my conversation. Still, as we talked, I enjoyed a certain sort of insurgent power. Will they really bring me on? I wondered. Do they suspect that I might share affinities with the socialists and the Luddites? When we were done talking, I told Qingling that I hoped to hear from her again soon. I shut my laptop and gazed at the tight borders of my childhood bedroom window.

A day after talking to Qingling, I received a phone call from the recruiter. I had just finished work at the café, so I untied my apron and sat outside on the patio. She told me that The Startup would like to offer me a 60-day contract-for-hire position as a Content Operations Analyst. Work would be full time and paid hourly, and they’d like me to start as soon as possible.

“We believe in extreme speed,” she told me. I said that I would need a little time to think about it. She gave me four days and asked what date I could start working. She looked forward to reconnecting shortly.

I can’t pinpoint when exactly working for The Startup became something that I began to consider, but it did, eventually. I’d been going through the application process mostly to appease my curiosity, and had never thought that I’d actually follow through with any of it. In fact, I’d looked on all of my peers who’d joined the tech industry with contempt. What sellouts, I thought, of course an Econ major would take a job at Intuit. I thought it vain to seek this type of success, selfish, greedy, and shortsighted.

More importantly, I believed, and still believe, that much of what goes on in Silicon Valley makes the world worse and less livable. I wrote my senior college thesis on the idea, exploring the nexus of technology, capital, body, and environment as it tangles wirelessly—and perilously—in the object of the smartphone. If I had allegiance to anyone in the tech world, it was the ethicist Tristan Harris of the Center for Humane Technology, but even his ideas seemed unduly clouded by the Bay’s fog, hemmed in by the valley’s swaddling hills. Only someone so constrained could think it appropriate to call what’s happening in tech, “human downgrading,” as if the only vocabulary we have available to us comes from the bits and bytes of compu-speak.

Here I was, though, sitting on the sidewalk, my morning shift at the café done, an evening of bartending looming just beyond my afternoon. When I finished working, I would return to my parents’ house, which would be silent and cavernous and dark, and then fall asleep alone, exhausted.

The notion that this particular pattern of life might soon end gave me a jolt of energy. Maybe I could earn enough cash to buy some future wiggle room. Maybe I could learn some filming and editing techniques that would help with my next move. Maybe—and this was the possibility that frightened me most—I’d actually enjoy it. The Startup might offer the intellectual challenge and sense of striving that I’d been missing since college. I might feel energized by the competition, invigorated by the hustle. When my cousin and her family offered me a free room at their house near the office, I called the recruiter and told her I was in.

All the new hands gathered in the conference room for our first meeting. After a brief welcome, the recruiter pulled up a Powerpoint and began defining The Startup for us.

“We want to be for short video what Vice is for media. What Audi is for the automotive industry. We want to be like Nike in retail, Etsy in e-commerce,” she began. “Do you know what we mean?” Slide.

“When, early on, we were trying to define ourselves to investors, we came up with this list of descriptors: we are unconventional [slide]; we’re elevated [slide]; we’re entertaining [slide]; we’re useful [slide]; the last word is community.”

The recruiter continued into a brief history of the company, beginning with the founder discovering an undercapitalized short-video marketspace and moving on through the typical startup stages—a business partner, investor cash, a small early team, some more investor cash, proprietary software, bigger investors, and eventually a usable app that had yet to attract very many users.

“When we began, we thought that our user base was preteens and teenagers, but our data showed that we had better luck with people in their early twenties, so we pivoted. As a company, we are data driven. Data has made us into what we are today. We’re always searching for that 100x idea to bring us to the next level,” the recruiter said.

“Now I’m going to show a couple of our top performing videos,” she continued, “but you should all really spend time watching more yourselves. In fact, it’s one of your onboarding activities.”

We began with some of the platform’s mobile TV shorts, produced by a satellite crew in Los Angeles. One was about being a broke millennial, while another concerned a struggling movie actor. Both were intended as comic, but I remember them mostly as poorly acted, mildly sexist, and desperately unoriginal. The recruiter seemed proud.

“That’s all I have for you now,” she told us. “Good luck with your onboarding videos, and remember to take time to learn and enjoy our platform.”

We closed our notebooks and hobbled back to our desks. The electronic music pulsed forward.

After lunch, we convened in a conference room to listen to my new boss, Qingling, familiarize everyone with the work of the content team. She clicked to the first slide of a very pretty Powerpoint. Seated and fiddling with her laptop, she gave us her name and cut straight to business.

“The content team deals with videos, not creators. Our goal is here:” Quingling moved her cursor to the top of the slide and began reading. “Help people enjoy the unique quality of videos on and only on [The Startup’s app].

“We do this in three ways: content direction, content management, and content production.”

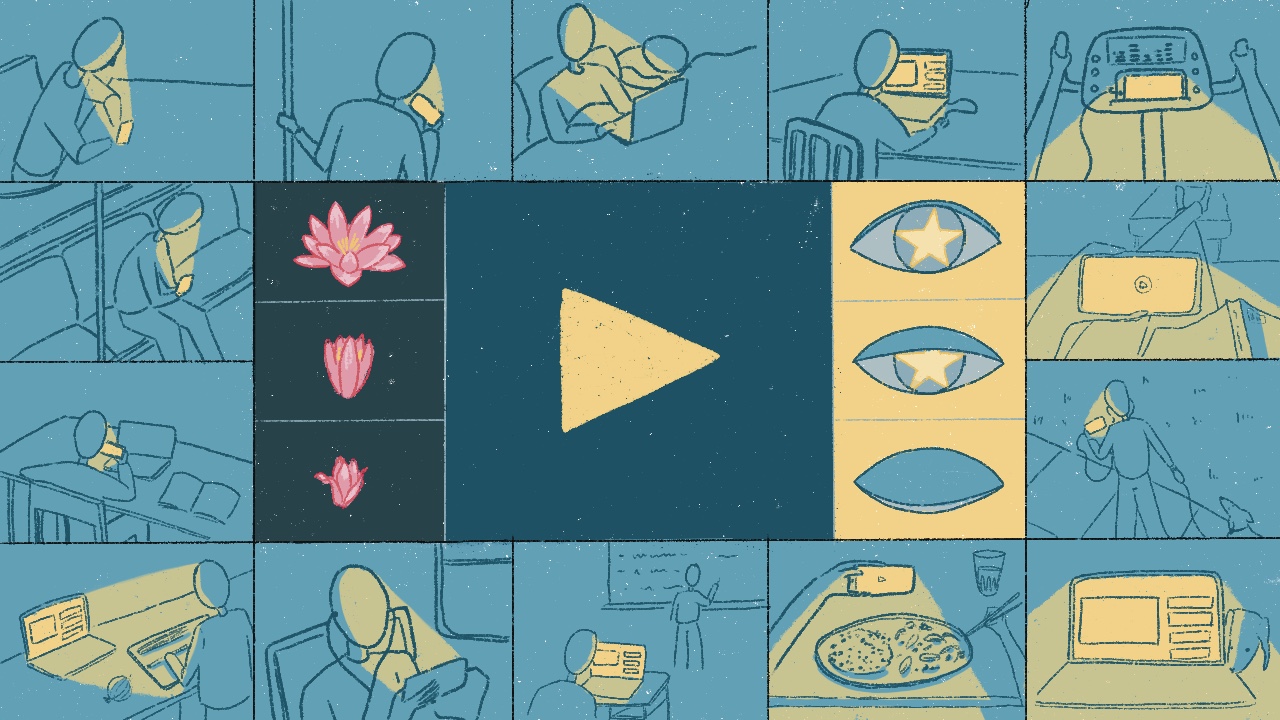

As Qingling broke down these categories, I first began to understand what my work day might involve. The content team was responsible for learning which videos were performing well, and why. With this knowledge, it was supposed to predict what might be popular in the future, prototype and test videos that might capitalize on these trends, and then send those ideas out to influencers who could execute them for a mass audience. What this amounted to, mostly, was watching a lot of videos on the app and keeping abreast of pop culture. I sunk down in my chair.

“Our videos should do one of three things,” Quingling read from her computer.

“1. Fulfill/exploit human nature

“2. Trigger intense viral emotion

“3. Relate strongly to the target segment

“Any questions?”

Nobody raised their hand, so Qingling shut her laptop and the meeting adjourned. Returning to my desk, I popped open a seltzer from the staff fridge.

In addition to the orientation meetings, our first few days of onboarding were meant to familiarize us with the world of short video. According to our assigned readings, short video was primed for a global explosion. With heightened streaming speeds, ascendent video quality, intuitive editing software, and ever-shortening attention spans, we were one app away from a global phenomenon.

Arguably, we were already there. Tik Tok, our biggest competitor, had logged over a billion downloads since its launch in 2017. The Startup bargained that this dominance was only temporary, though, a blip buoyed by trendy adolescents and unlikely to expand to older users. Higher powers at our company believed that no app had yet claimed total supremacy. The race was still on, and we needed to understand our competition.

Hence, an enormous task-load of video watching—something like 500 videos from each of our seven closest rival platforms, including a selection of 50 videos from each app that we personally enjoyed. This was supposed to breed familiarity and industry knowledge, but I thought of it more as something akin to hazing. It was the most grating sort of boring. Video after video, moments shattered into tiny eternities and time compounded on itself.

Any duration felt at once overfilled and completely vacant. When I needed a break, I tried reading one of the 60-odd articles about short video linked in our onboarding packet, many of which were written in Chinese (several of The Startup’s leaders hailed from China). This proved much more entertaining, since I don’t speak the language and had to instead read through Google translate, which spit out gem after gem of intriguing nonsense:

The three winning methods of vibrating the sea are “protecting the local content ecology,” “lowering the threshold of users to shoot video” and “a large amount of advertising.”

Next, let’s follow the girls to feel the full dry goods!

Especially after becoming a father, because he began to share more aspects of parenting, emotions, etc., he became a ‘friend of women,’ and the fans were very sticky.

And a heading: More than enough content, social hopeless.

We were held accountable to these tasks by a slideshow showcasing our learnings, due the following week. As hours passed and I failed to make progress, I could sense a queue of videos stacking up further and further behind my screen. It seemed endless. By quitting time—7:00 PM—the red balloon attached to my desk had lost its lift and sunk down to the floor.

A WWE wrestler gainers from the ring ropes, landing head-first on his opponent.

A dog in a shark fin life vest sprints toward the end of a boat dock, where it slips and flies into the water, its legs a’wheeling.

The next morning, I ran through Atherton, the most expensive zip code in America. With broad streets shaded by giant umbrella oaks, it seemed like an excellent place to jog from my cousins’ house in the adjoining neighborhood. I set out early, crossing a busy arterial before entering the lonely quiet of obscene wealth. I ran by giant walls and sturdy metal gates. I saw few residents and a lot of help—gardeners, landscapers, and contractors, all buzzing like harried worker bees.

Every other street seemed to be a dead end, and I eventually lost myself in the maze. Is this what it meant to run the Valley, to lose yourself and then be consumed by it? I continued to wander, passing a neighborhood library box and discovering a copy of Saul Alinsky’s 1971 handbook, Rules For Radicals. Palming it, I mazed my way home.

Rule #7: A tactic that drags on too long becomes a drag.

Later that day, the content team convened for a brainstorming meeting. We were supposed to bring in ideas for different personas, formats, and topics, because, as we learned the day before, Concept = Persona + Format + Topic. If you have all three, then you have a single video. If you have unlimited topics, then you have unlimited videos. It was a formula that pumped out variations on the same thing, again and again—a motor to keep the app rolling.

“So, what are your ideas?” Qingling asked from the front of the room.

“What if we made videos about everyday annoying occurrences?” somebody ventured.

“What do you mean?” said Qingling.

“Like when your Bluetooth won’t connect, or, uh, when somebody’s backpack keeps hitting you in the face on the BART?”

“What is the persona?” asked Qingling. “And what is the format? You need a persona and a format, otherwise there is no concept.”

Qingling moved on. “We have a new BA (Brand Ambassador) from TA (Talent Acquisition),” she said. “We need to decide if any of our preexisting personas will work for them. Any ideas? Oscar?”

“I don’t know anything about her,” said Oscar, a young guy with tired eyes and messy blonde hair.

“That’s why we need a persona,” said Quingling. “Think about it and Slack me your ideas.”

On Wednesday, the content team gathered for its internal onboarding meeting. Qingling projected a slide that read, “When Research Isn’t Boring.” “Ugh, my mind is super dry,” she began, squinting and adjusting her glasses. “Okay, today we are going to talk about research. Each of you is going to do three types each week: Format, Trend, and Topic Research. I know it sounds boring, but it isn’t, I promise.”

The meeting was long and confusing. Qingling had devised a broad plan for our six person team to cover all of U.S. culture, with each individual in charge of several different beats. From then on, I was to track important events (of what type, I wasn’t sure), and make a video about them daily. On a weekly basis, I was tasked with forecasting potentially viral topics in the art, beauty, and science/technology worlds. Finally, each Tuesday, I was responsible with ideating and prototyping one to three video concepts, complete with personas, formats, pros, and cons. The hope, it seemed, was that this relentless scattershot would eventually land a big hit.

Snacking on a sleeve of trail mix, I thought of all the videos that I’d have to watch, all of the tweets that I’d have to read, and all of the trends that I’d have to learn and relearn each and every day. And to what end? I saw little time for quality production, and even less for learning new skills. I would become a white collar video grunt. Crumpling the empty plastic wrapper, I returned to my desk and consulted my contractor’s agreement to see how trapped I was.

Later, we convened for a welcome presentation from the CEO himself. Calvin had cut his teeth in finance, made a feast, and then transitioned to tech for some sort of masochistic dessert. He began by relaying to us a familiar myth of success, one in which he began as a coffee retriever at J.P. Morgan and eventually—through long hours and hard work—crawled his way up the twin ladders of wealth and prestige.

“All you have to do is take ownership of your work and deliver,” he said. “That’s the most important thing. That’s what we value. If you show up, if you deliver, there’ll be a place for you here.”

Calvin carried on into the company’s history (renting an AirBnB and working in a Starbucks), its goals (10 million users by August), and its methods (A/B testing and pirating influencers from other platforms). In his telling, the whole operation sounded like a knock-off of one of the Valley’s much-fabled unicorns.

Calvin didn’t really care about short video. Calvin was a finance guy. He cared about investor capital and massive returns. He cared about growth curves shaped like hockey sticks. What mattered to Calvin was the sort of success that seeded itself in paper coffee cups, sprouted in repurposed garages, and then went rampant, worldwide.

In truth, we had a derivative product in a crowded market space, and the only thing keeping us rolling forward was a steady flow of investor cash. The question was whether or not that money would last us until we fumbled our way into becoming a product that people actually wanted to use. I was not so hopeful, but I also wasn’t a millionaire.

A man tries to catapult a basketball off of a skateboard and into another man’s testicles. The ball flies into his face and he collapses onto his back.

A chimpanzee watches a video of a chimpanzee on Instagram. He swipes to an image of a woman in a bikini.

A drone glides over the lush farm fields of Indonesia.

After lunch on Thursday, we met in front of a projector to learn about the work of the product team. The presenter was young and quick, with heaps of energy. He had composed all of his slides in the form of memes.

“We want our product to be like Cinnamon Toast Crunch,” he told us. “Does anyone know what I mean by that?”

“Sugary and addictive?” someone asked.

“Not quite,” he said. “But also, yes. Cinnamon Toast Crunch creates a daily habit by tasting so good. Though we maybe don’t want to be quite as exploitative as Cinnamon Toast Crunch—we don’t want to kill our users—but we do want them coming back. We want to create a habit.”

The audience nodded in understanding. The next slide showed Hot Pockets.

“Hot Pockets are a beloved brand. People love Hot Pockets, especially stoners. If stoners loved our app, that’d be great. Make sense?” Chuckles, slide.

“We also want our product to be like AirPods. Any guesses as to why?

“Everyone wants them,” somebody asserted.

“Status symbol?” another guessed.

“Yes and yes,” said the presenter. “But more, we want to be like AirPods because AirPods present a new form factor that changes how people consume. With AirPods, people are connected all the time, and that changes the use possibilities for a whole suite of apps.”

The presenter continued to talk about all of the features on our app that helped retain users, as well as how they were proven to work (A/B testing). He likened his team to the predator snakes who, through natural selection, teach their victim mice to behave in certain ways. It was a dicey balance: we had to direct the user without wholly consuming them. The person who finds herself bloated from eating too much Cinnamon Toast Crunch will throw the box out. The well-trained user will eat it regularly without ever recognizing excess.

When I returned to my desk, I thought about how addiction is a form and not a filling, a desire whose object could be anything. That our goal was to shape that dynamic unsettled me. The enterprise seemed fraught with responsibility, and yet The Startup treated it like a fun puzzle animated by cheery rewards. I wondered if other employees felt the weight of our potential success, and whether or not I wanted to share that burden.

A cake time-lapses into the face of Macauley Culkin clasping his face and gasping in Home Alone.

A flaming marshmallow is rolled into a tulipped latte, where it extinguishes itself.

For the rest of the afternoon, I focused on my onboarding assignment so that I could move on to all of my new research tasks. I watched video after video on Douyin, Vigo Video, TikTok, and other apps. I stretched for things to admire about them, searched for the small details that distinguished one from the other.

Often, the same video (or what seemed to be the same video) played across platforms. Image after image pleaded for attention. A light pink orb pulses with pale purple bubbles as lullaby music runs softly in the background. The office flashed and flexed around my phone’s 4.7-inch screen. The title:“For Insomnia People Only!” I looked to Qingling and the other people at my pod, their fingers fanged into their keyboards, just barely hanging on. Did they enjoy all this? What were they here for? Maybe, I thought, they too recognized this as a charade and were just playing along. They had rent to pay. Many were here on work visas. How else could anyone afford to live here? What else can a person do?

My eyes throbbed. I closed them and imagined long horizons and the open room that a Wyoming friend had jokingly mentioned the week before. I remembered that I was lucky enough to be an adult who could live elsewhere. I remembered that there was a world beyond my screen and that there were values beyond money and growth.

A skateboarder bungees himself toward a ramp. His wheels catch on the lip and he flies into a dumpster.

Once quitting time graciously arrived, I packed up my computer and began to leave. Qingling leaned under her screen, skeptical of my departure. “Hey North, can you come here?” I walked around our pod to meet her at a spreadsheet.

“I’m actually about to go,” I said. “I can talk for a minute but I have to catch my ride.”

“This is a document with all of the big U.S. events on it,” she said. “It has all of their dates, too.” I saw when the Oscars were, the CMAs and the VMAs.

“That’d actually be really helpful,” I said, sensing a boon. “Can you send it to me?”

“No,” Qingling said. “If I send it to you, it will limit you. I want you to use your own ideas.”

“No, you won’t limit me—you’d just help me plan. There are plenty of days that aren’t on that list that I’d still use my own ideas for,” I said.

Qingling seemed unconvinced. I tried to explain how I’d probably use those events anyway, and that having the list would help me be more efficient. She disagreed and looked at me with concern.

That night, I texted my friend in Wyoming. Hey, is that room still open?

It was. Relieved, I felt my job fade from obligation to option.

Friday brought fewer meetings and more work time. I finished the slide deck for my onboarding assignment and then made my first event video—an explainer piece about poppies for the upcoming Memorial Day long weekend. My dread and disorientation streamlined into a sense of direction. I felt quick and capable. Was this an energy that I could maintain if I stayed? Or was it simply my body celebrating the knowledge that I could leave The Startup whenever I wanted? It was hard to tell.

I worked through lunch until our afternoon all-staff stand-up, As part of the onboarding process, we had been asked to film short self-portraits and upload them to The Startup’s app. As the videos rolled, I found myself standing next to Calvin. He stared at the screen with such intensity that I wondered what he was seeing. Was this his vision coming to fruition? The start of a movement? Could Calvin see what I saw—shaky clips nauseated by superfluous production effects? It occurred to me that Calvin might be so enthralled by The Startup’s metrics and self-storytelling that he had become blind to the content of the app itself. Video was not his expertise, after all—numbers were. Then again, his stern gaze might actually be masking some sort of disappointment with our work.

I felt especially conscious of this possibility as my video began to play. The clip begins with a static shot of a grassy knoll, underlined by a concrete path and topped with trees. I walk into the center of the frame, sit down, and sip a cup of coffee. A voice-over introduces myself and my hobbies as the image cuts violently to different illustrations of my various foibles—climbing, skateboarding, goofing off with friends. The video ends with these lines and a montage of roadkill stills: Once, I found a dead squirrel, and it’s been on my mind ever since. If you look, you see things, before they disappear. In slow motion, I fling myself from the top of the frame, backflipping off of a tall cliff, to the water far below.

As the screen cut to black, Vincent turned to me and said, “That was good. You should be one of our influencers.”

A weimaraner looks stunned as a rawhide bone protrudes cigarette-style from its jaw.

A man sprints to jump over a PT Cruiser as it flies toward him on salt flats.

The meeting broke and everyone scattered toward the office games and beer fridge. I went back to my desk—there was still time before the company barbeque at 7:00 P.M, and I had work to finish. Despite my best efforts, though, I couldn’t complete the trend reports that were due for our meeting on Tuesday morning.

With weekend plans to fly home to Washington State for a relay race, I knew that I wouldn’t have much time to get the extra work done. Besides, on principle, I didn’t want my new job to bleed into my weekend so soon. I walked around to Qingling’s desk and apologized that I hadn’t yet finished my reports. She looked at me quizzically, as if to point out that Tuesday was a full three days away. I elaborated.

“I value my free time and don’t want to work on the weekend. Plus, I don’t think that I have overtime status on my contract,” I said.

“So you won’t deliver?” she asked. A nearby college intern perked with interest.

“No, I guess not,” I said. The intern’s face opened in terror.

“Well, if you’re not going to deliver, then we’re going to have to rethink whether or not you’re a good fit for us,” she said, putting her headphones on and walking away.

A white woman grabs a wine glass and breaks it against the counter, lip-singing to Beyonce.

A man dressed as Mario tre flips a five stair as his friends dance to a parody of Macklemore’s “Thrift Shop.”

I tried to enjoy the barbeque, but felt guilty and distracted. I don’t like disappointing people. Qingling already seemed stressed enough. She couldn’t have been much older than I was, and yet she was personally accountable for all of the content on an app built in a language and country that were not her own. Fifteen minutes later, I pulled her aside.

“I’ll finish my work on the weekend this time, but in the future I hope that we can be more proactive in communicating about work tasks so that I can deliver and still enjoy my weekends,” I said.

“There are many ways to do that,” said Qingling. “You can work harder and more efficient. You can work smarter. This is a startup and you are part of a team. We all work together. You should love your work and take ownership of it. That’s what people at startups do.”

“Okay,” I said, “but I do value my non-work time, too.”

Qingling lowered her brow and looked away. We left the conversation there. I ate a veggie burger and some salad and then left without saying goodbye.

Shaving cream squirts into a metal spaghetti press. Bendy tubes squirm out like little white worms. #oddlysatisfying

I flew home the following morning to meet some old friends for a relay race that took our team from mountain to sea. Over finish line beers, we caught up on life and talked about where we’d landed. I told them about my shock at The Startup, how it felt so parodic even as it commanded millions of dollars and the lives of so many smart people. They let me vent before affirming that there was little sense in engaging that empty hustle, chasing trends and slapping together videos all summer long. With their support, I felt justified in bailing so soon.

My plane landed back in the Valley on Monday evening. After finishing up my trend reports, I thanked my relatives for their hospitality and, with some embarrassment, told them that I’d be leaving. They were a touch flummoxed, but understanding. Aunt Betsy needled me for being sensitive, and Uncle Mike chuckled at my capriciousness. They asked me where I’d be going.

“Jackson, Wyoming,” I said, surprising myself with the statement’s certainty.

“When?”

“Maybe two or three days from now?” I ventured. I knew neither how far away Jackson was, nor exactly where it sat on a map. I would learn the details later.

It takes about fifteen hours to drive from Silicon Valley to Jackson, Wyoming. I did it in one day, with plenty of time to think. Once the site of so much innovation and promise, it felt strange to encounter a Silicon Valley that chased its tail so vigorously. I wondered what would happen to The Startup. Would it be bought by a Google or an Instagram? Would its trend-hounding approach eventually land an audience? I didn’t know, but I also didn’t much care to find out.

Jobless and cruising the highway, I felt possessed by a broader sense of possibility than I’d experienced since graduating college. Reassured by my inability to make it in tech, I was on to explore new myths—of the Road, of the West—myths that I hoped would be more capacious, more flexible.

As I passed over the Sierras and angled toward the Rockies, I marvelled at how much of the world remained unscreened. Before me lay more than eyes and brain and image. There lived bodies, flesh, stone and so much more. I saw white-tailed deer, elk, sagebrush hills and the craggy peaks that preside over them. I saw wildflowers blooming from the snowmelt: aster, arrowleaf balsamroot, lupine, larkspur and so many others whose names I did not yet know.

There was space to move and there were stories to live. Switchbacking over the pass from Idaho to Wyoming, I rewound into springtime and thrilled in all of the growth that happens in small, slow, and particular ways. Here, life was just coming back from winter. I crested the hill and pressed down on my brakes.