In Here, in Prison, Rats are Treated as Children

Give me any living thing to care for so my mind doesn’t rest too long, longing for my children’s love.

This is my 4th funeral this week, and it’s only Wednesday.

As I sit on a bench with my right leg spontaneously bouncing, I take a deep breath of humid Texas air. It smells like cut grass. Mimi begins “Amazing Grace,” hitting the high notes like Whitney Houston, and we bow our heads. Jess starts wailing, “Jetta, oh Jetta, my baby!” Chris’s inability to read social cues is on full display. A look of confusion (or constipation) passes over her as she wrestles with whether to comfort Jess or flee. Opening a pocket Bible, Mimi recites a closing prayer.

This isn’t a church or gravesite. This is the Texas women’s prison where I’m incarcerated. Mimi is a preacher’s kid who officiates informal religious ceremonies, including funerals. Chris and Jess are an on-and-off couple. Their grief is genuine but their loss isn’t what you’d expect. They’ve lost a rodent that they co-parent as lovingly as they would a child.

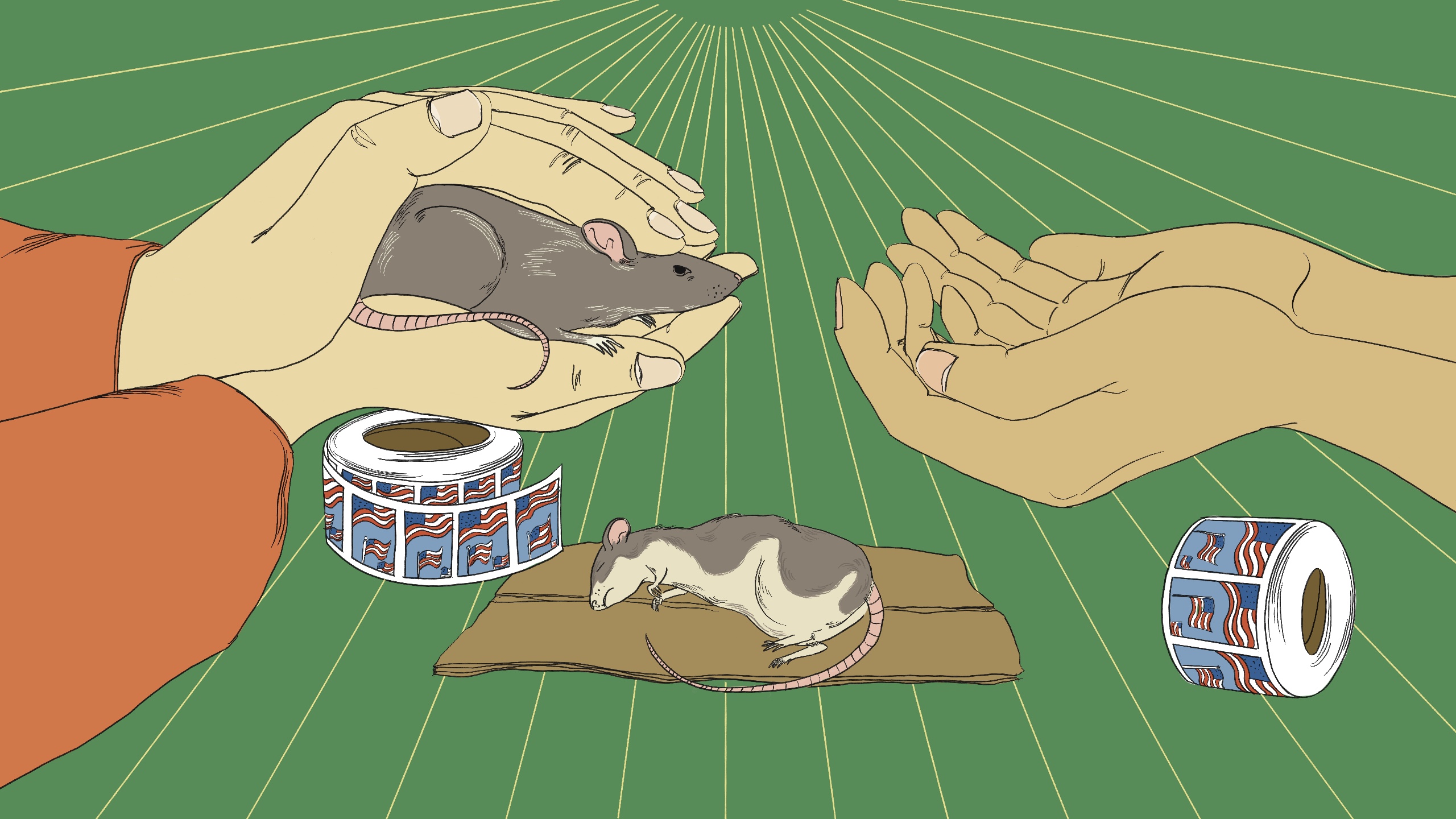

In here, an entire industry exists monetizing rodents. Rats are treated as children. They’re adopted, not purchased. The target market is couples, like Chris and Jess, who wish to complete their family. The rest of us are still heavily invested in these family dynamics and the market that emerged to create them. Being forced to live within impoverished small quarters means we all are maintaining communal peace.

Back at the funeral, a bell pierces the air and we follow Chris and Jess lining up behind them. It’s count time. The guards check our ID’s and offer sincere condolences on the loss of the baby rat, Jetta #5.

Jetta #5 lived almost a year, the longest of Jess’ children. Jess is known as a vocal rat advocate and doting parent. She admits that being away from her human children caused her to have suicidal thoughts and depression. Her five Jettas each fulfilled a painful maternal craving to nurture and feel needed without the side effects of psych medications, the only readily-available alternative.

Many of us here understand her longing to parent. The torture of listening to my son practice his saxophone; checking his homework; the monotony of making lunches, dropping him off at soccer practice. The constant bustle I never would have imagined missing is a distant memory behind bars. Understandably, all this pent-up desire to parent needs to be released: give me any living thing to care for so my mind doesn’t rest too long, longing for my children’s love.

And so a complex network emerged inside the two largest Texas women’s prisons. Different women play different roles, with some invested in the caretaking and others in the stamps, our widely-accepted form of currency.

At this prison, adoption begins with Callie, a fast-talking 20-year-old with the energy of an over-caffeinated toddler. She is known for her skills as a baby-rat procurer. At work, while everyone else hand-digs holes in hard Texas soil, Callie leads her crew, who dig into nests of baby rats for their next pick.

They hide the baby rats in the fingers of their work-gloves. At the end of the work day, we’re forced to strip naked for a body search before we enter the prison. As each person from Callie’s crew has a turn, the gloves are surreptitiously passed from people beside and behind them. It’s a team effort — we all help to distract the guards by talking and moving slower.

Back in the prison’s dorm day room, it’s all “Ooohs” and “Ahhs” as Callie’s team cups the tiny, barely grey critters, showing them off for adoption.

To adopt a rat, you have to go through Kandy. She makes and sells adoption licenses for 10 stamps. She also sells licenses for marriage and divorce. The old blues song by Johnny Taylor, “Cheaper to Keep Her,” applies to women’s prisons too, where divorce and custody “certificates” are 35 stamps. A reminder that marriage, like other trouble, is easy to get into and expensive to get out of.

Michelle is a self-described ratologist, with a packed bookshelf of knowledge she refuses to share. Geri, her first and only rat, has outlived everybody else’s. Geri is beyond clever. He instinctively discerns friend from foe.

Michelle can talk with correctional officers or the prison warden and nobody realizes Geri is with her. Once, a lieutenant ordered us to follow him to his office to rearrange furniture. Geri climbed under Michelle’s belly roll while he was talking to us, emerging only after the lieutenant left.

During lockdown, Michelle ties her tattoo ink (which is contraband, possession of which can send you to solitary confinement) to Geri. He jumps out her window and only returns when it’s time for lights out and the coast is clear. That rat could be in Mensa.

I get a sense of déj vu as I witness Michelle revel in the attention of being a parent. I’ve seen this movie before. She does what most parents with gifted children do: brag incessantly. The prison yard stands in for a child’s playground where — like competitive mothers in other gated communities — they loudly praise the other children’s accomplishments while secretly wondering, “Why can’t mine be like that?”

Parental insecurity feeds consumption in prison, too. Someone always has a gimmick, product or service they’re selling to “enhance intellectual development.”

Tiny, a portly and toothless middle-aged woman, is frequently seen walking around and advertising things rat parents didn’t realize they needed, which she guilt-trips them for not having. Today, she carries an empty shoebox selling “Brain health homemade granola bars! Good for all mammals! Only five stamps each!”

Tiny’s friend spreads the false rumor that Geri, the Mensa rat, eats these bars twice a day. Tiny sells out and begins a wait list for the next batch. Michelle vociferously denies feeding Geri such trash; nobody believes her.

Most families face the challenge of caring for rats while working. Every incarcerated person must work unpaid and/or attend school. Refusing to do so results in disciplinary infractions that will lengthen your prison stay and send you to solitary confinement.

Flo, a retired woman who uses a walker, is one of the few with medical restrictions which prevent her from working. Stuck in the dorm’s dayrooms, she opened a rodent daycare which only accepts older, trained rats. Her services are in high demand. Flo won’t accept any new clients in her daycare without an exorbitant deposit of 50 stamps. She ties Kool Aid dyed shoelaces around the rats to tell them apart. She sits on the dayroom bench as they scamper.

There are rules that dictate this complex world of adoption, parenting and caretaking. Referring to these children as “rats” is an open invitation to fight.

It is common for fights to break out because someone disrespected the “child” by calling them a rat instead of their name. A newly-arrived girl’s face was splashed with hot coffee, then bashed in with the cup. An argument between a couple ended with one slicing the other with a razor across her cheek.

Rats must be fiercely hidden. Having any pet is a clear violation. If discovered, worse than the disciplinary infraction is that an officer will violently kill the rodent in full view of everyone. This is done to deter future adoptions.

Prisons are brutal, lonely places. We are famished for the social contact our species demands. But the risks that rat parents take are worth the rewards. The rats push all of us to a deeper, stronger, relentless commitment to the fundamental right to parent.

Following Jetta #5 funeral, we soberly return to the yard bench and return our attention to the grieving couple. Suddenly, Chris presents Jess with a surprise: Jetta #6. ▩