Postcard from the U.S. Open

The Ballboy Diaries

Stan Wawrinka was locked in an extremely tense service game in his second round match against Jeremy Chardy at the 2019 U.S. Open. He had warded off multiple break points, and it was now the fourth or fifth deuce of the game. As the ballboy, I was sprinting his towel out to him after every point. The tension of the moment was getting to me—I was nearly as out of breath as he was, and way more on edge. Sensing my nervousness, Stan took the towel and smiled at me. “Relax. It’s alright, man. Can you talk? Say something. It’s alright!” I was in disbelief. Couldn’t muster any words. He tossed his towel back to me and I ran it back to the corner. He coolly served out the game and won the match in four sets. As soon as the match ended, I sprinted back to the U.S. Open ballperson locker room, itching to tell Ben about what had just happened.

From the ages of 10 to 17, Ben and I were what you might describe as best friends. We shared experiences—our baseball team traveled around the west coast winning tournaments, and we played as doubles partners in junior tennis tournaments across the Pacific Northwest. But most of all, we spent endless weekends and summers at one of our houses playing games. Madden 2004, ping pong, Smash Bros, wiffleball, MVP Baseball 2005, tennis, baseball, Mario Kart—whatever struck our fancy, we’d find a way to alter the rules to make it funnier. These games occupied hours, days, weeks, months, years.

Ben and I never went to school together growing up. Our friendship existed beyond the social constructions of middle and high school. My school friends and I were interested in grades, girls, and getting fucked up—our interactions were inevitably colored by the need to fit into the social ecosystem of high school.

Hanging out with Ben was an escape from that reality—from all reality. We played the same video games, played the same sports, and made the same jokes we’d been making since we were 10. We didn’t have to talk about anything but what we were doing. Nothing else in the world mattered, or even existed when we hung out. My high school girlfriend got pissed at me because we’d been dating for a year and I hadn’t gotten around to telling my best friend—there just wasn’t a need.

Our friendship was its own parallel universe. Upon entering Ben’s front door, there was a small landing with a stairway on the left leading upstairs. On the right, a stairwell led to the basement—the portal to our universe. There, a room with fuzzy white carpet and stucco ceiling had everything we needed—an N64 and a PS2, ping pong, Sweet and Salty Nut bars, and Dr. Pepper.

After attending different colleges, Ben and I both lived in New York City for the past five years. Our friendship largely stayed the same as what it was like when we were kids. We didn’t talk much about our jobs, our relationships, the various trials and tribulations of the real world. Instead, we went rock climbing, ate at shitty diners, played tennis, and played the same old sports video games we played as kids. The only difference was that now we both had working lives, adult responsibilities, and significantly less time to hang out and escape reality.

Ben and I had discussed for years, half-jokingly, the possibility of trying out to be ballboys at the U.S. Open. Last summer, with my Ph.D. defense approaching, our time living in the same city was rapidly dwindling. I was going to be moving to Los Angeles for a new job in October. We decided to actually go through it, as a symbolic capstone to our in-person friendship—we figured it would at least be fun to say that we tried out.

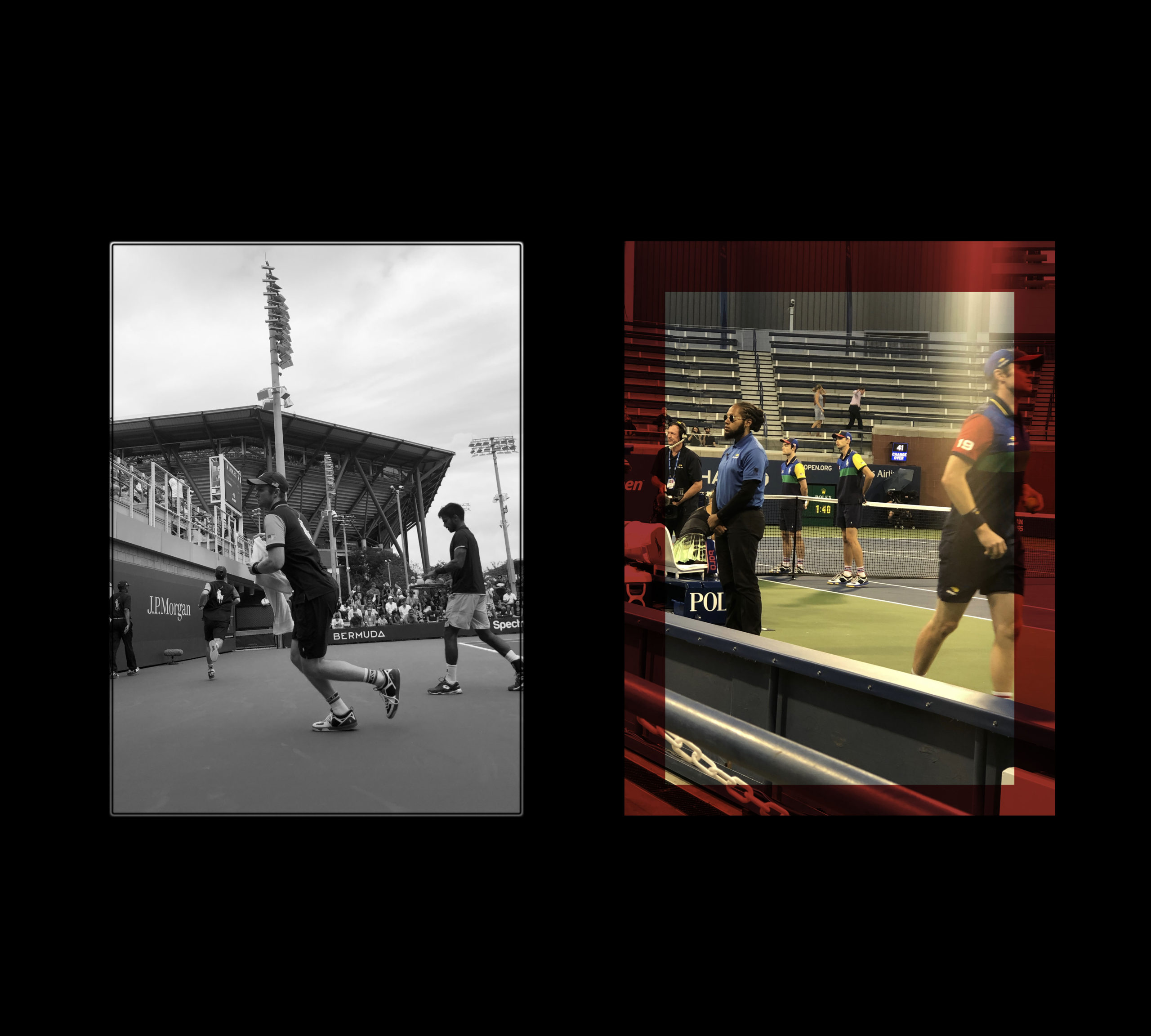

On a cloudy evening in early June, Ben and I arrived at the first tryout in Flushing, Queens armed with our non-marking shoes and a lifetime of tennis experience between us. We had absolutely no idea what to expect. We were immediately mistaken for parents bringing our children to try out. The median age of a U.S. Open ballperson is about 16.

During the tryout, a teenager hit balls into the net, and we ran across the court picking them up. We practiced rolling balls back to another prospective ballperson at the baseline. Afterwards, Ben and I conferred, agreeing that we thought we did pretty well, but worried that some of our rolls had been too bouncy.

Three weeks later, I received an email with the subject line 2019 US Open Ballperson and “congratulations” visible in the email preview. I promptly lost my shit. I texted Ben—he received the same message. We were actually going to do it. How absurd was this?

After three one-hour training sessions, I showed up to the first day of U.S. Open qualifying feeling like I had absolutely no idea what I was doing. Decked out head-to-toe in the Ralph Lauren ballperson uniform, I jogged out with five of my teenage compatriots for my first tour of on-court duty. I don’t remember much except being exceptionally stressed out during every single point. I think Mischa Zverev was playing. I felt like the weight of the world rested on my shoulders—one subtle fuck-up could potentially alter the match.

Being a ballperson is highly situational. Every moment demands intense focus, and a working hypothesis for what to do when the point ends. What is the score? Will there be a changeover? Where are the rest of the balls? Will the player need his/her towel? Will it be time to change out the balls for new ones? Anticipating these questions is crucial, but adaptability is key. A player might smash a racket, and you would have to pick up all the pieces off the ground.

My four days working the qualifying matches went pretty well. I started my first day of the real tournament feeling like I knew what I was doing. I was dead wrong—the quality of play in the matches was way higher, as were the expectations. One minor lapse felt like a gargantuan mistake. Almost immediately, I got chewed out by Gilles Simon for not bringing him his towel quickly enough.

Over the next couple days, I built my confidence back up. Confidence is key for a ballperson. Second guessing leads to slow reactions, which leads to mistakes. Instantaneous recognition of which tasks need to be done, in what order, at what pace, by which person, in which place on the court is what makes a good ballperson. Simultaneous recognition of these things by all six ballpeople on the court is what makes a match run seamlessly.

Looking back now, the matches I worked feel like a blur. A few moments stand out—a 360 smash on match point by Gael Monfils, Stan Wawrinka cracking jokes, handing a towel way up to 6’9” John Isner then immediately afterwards having to hand a towel way down to 5’6” Diego Schwartzman, working the men’s wheelchair singles final, standing 100 feet away from Meghan Markle, and firing off confetti after the women’s singles final.

But more than any single moment, the feeling that has stuck with me most powerfully is the sheer intensity of experiencing professional tennis on the court—as a participant. I was a part of each match, a part of the U.S. Open. My aspirations of becoming a professional athlete ended at the age of 14 or so, but every moment I spent on the court during the tournament felt like I was living out a childhood dream.

Ben and I didn’t get to work together much during the tournament. Every ballperson alternated between a one-hour on-court shift and a one-hour break, and our schedules were almost always staggered. For ballpeople above the age of 18, not restricted by pesky child labor laws, hours could be extremely long. We would show up at 10 or 11 a.m. and work until play concluded—sometimes as late as 2 a.m.—then arrive back at the tournament grounds at 10 a.m. again the next day. When our shifts ended at the same time, we’d share a taxi back from Flushing to Astoria, swapping our stories from the court each day. On the second to last day of the tournament, Ben and I finally got to work a match together. It was the junior girls’ singles semifinal on Court 17. He was a net and I was a back. Our ballperson chemistry was seamless.

For those three weeks, Ben and I shared an all-encompassing experience completely separate from our otherwise normal, working-adult existences. I’d wake up early to work on my dissertation for an hour or so each morning, then ditch real life and head to pick up balls and fetch towels at the U.S. Open. We were reliving our childhood, hanging out in Ben’s basement all over again, detached from reality without a care in the world. It was escapism, and our friendship, at its finest.

The end of the U.S. Open was accompanied by feelings of profound emptiness. The day after it concluded, I woke up, made a couple final edits, and submitted my 250-page dissertation—a comprehensive study of the chemical oceanography of two arcane radioactive isotopes, thorium-230 and protactinium-231. I’d spent the past five years busting my ass on it, and I felt nothing. I didn’t care about the real world. I wanted to spend 12 hours a day picking up tennis balls, delivering sweaty towels to professional tennis players, and swapping stories about it all in a midnight taxi home afterwards with Ben.

The end of the tournament meant the end of my thesis, which meant the end of my time in New York. I worried this would bring with it the effective end of my friendship with Ben—my oldest friend in the world. An escapist friendship is seemingly predicated on experiences shared in person, not from across the country.

Ben and I both thought that our ballperson experience would be a one-time thing, even after the tournament ended. Ben didn’t think he could justify taking three weeks off work for it two years in a row, and I thought there was no way I could skip out on my job in Los Angeles. With the pandemic, I don’t know if the U.S. Open will happen this year, but the powers that be are preparing as if it will. We both got emails asking if we would return as ballpeople. We’ve both filled out the paperwork. If it happens, we’re going to do it again. It’s just like when we were kids, just at a bit slower pace. Our friendship won’t end—we’re at the landing of his house, perched at the top step of the stairway, heading down to his basement.