Sell My Sole

If there is one thing the current state of culture has given us, it’s choices. Many, many choices. An appetite for cultural consumption entails scrutiny of musicians, writers, chefs, and everything else we could possibly have an opinion about. With all this effort being expended, we naturally feel that we have given something of ourselves to whatever it is we’ve chosen to bestow our all-important ‘taste’ upon. When something we like suddenly leaves a sour taste in our mouths, we don’t only want to spit it out. We want to create a spittle-filled impressionist painting of our disgust on the social media canvas to show everyone just how shitty it tastes. Only, we’re really no different than children spitting out something without thinking just because they don’t like how it looks and they “don’t” eat Chinese food. Amid their exploding fame, Macklemore & Ryan Lewis are the latest to experience this phenomenon.

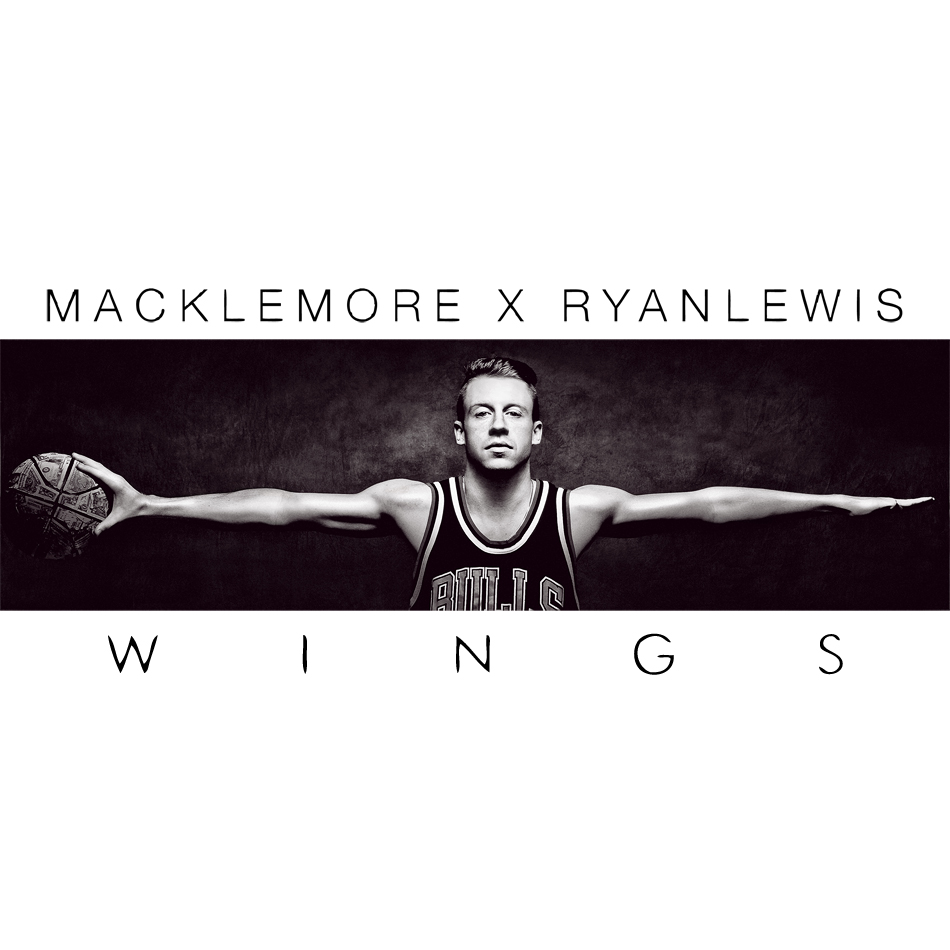

About a week ago, Macklemore & Ryan Lewis unveiled their latest in “holy-shit-we-aren’t-signed-how-did-we-do-that” moments” by releasing and promoting an adapted version of their song “Wings” for the upcoming NBA All-Star Weekend. For many this was nothing more or less than impressive. However, for Macklemore fans who follow his music more closely, this amounted to nothing less than Brutus stabbing Caesar while telling him that his wife tastes like Cheerios. In more literal terms, he was quickly accused of selling out for the big bucks.

This kind of pseudo-controversy isn’t new to Macklemore. His clean-cut image, wholesome, positivist messages, and soccer-mom-liberal political views make him an easy target in the hip hop world. Of course, none of this bothers Macklemore. Listening to his lyrics, one of the clearest themes is that he doesn’t want or need to fit into any box, even the one many of his fans love. He spent enough years trying to be something he’s not through drug use and abuse, and through his sobriety he’s found a kind of self-assuredness that only leads to success. He is more than happy with his millions of fans who adore him (sometimes to an almost idolatrous extent) to be affected by the “hardcore” rap blogs that label him as a poseur or co-opting white guy — pariahs in the hip hop world. Given the impervious nature of Macklemore’s brand, it’s only logical that his biggest detractors are his most vocal fans.

Macklemore & Ryan Lewis remain unfazed by their critics and humble in the face of adoration, driven by a conviction in themselves and comfort in their own skin. In his song “Wings” Macklemore tells the story of his love of sneakers. Part of that story is his realization that people are willing to steal and murder to get the sneakers he so loves, and the self-questioning that comes from realizing something you love may only be hurting you and everyone around you. He ends by stating that he is “trying to take mine off,” which is to say, stop obsessing over Nikes and their marketing driven brand. Taking his final words as gospel, it does seem contradictory for him to lend his brand and song to the NBA, an unabashed proponent of consumption (and Nikes). Given these apparent contradictions, it’s easy to say that Macklemore has sold out on his ideas for what ever it was the NBA was offering. The problem is, the easiest thing to say isn’t always the most accurate.

Being labeled as a sellout is nothing new for musicians. Take Bob Dylan (who, I would like to make clear, I am not comparing Macklemore to). After attaining an enormous following by writing and performing socio-political American folk songs, he made a leap into rock ‘n’ roll and away from social issues. To him it represented a disillusionment with himself, an all too human loss of faith in both his ability to enact change and society’s ability to accept it. To his audience, it felt more like this:

Movie adaptations aside, the audience hated the new sound and quickly branded Dylan as a sellout for abandoning his protest songs. Looking back, Dylan’s transition away from protest music was a natural process of growth for him. There are many who prefer his rock music to his folk songs. Nevertheless, at the time abandoning folk music meant Dylan contradicted everything he had previously stood for, even if he personally didn’t feel that way.

Dylan and Macklemore’s cases are not the same. Dylan changed his sound and his content, but never refuted anything he previously wrote. Macklemore implicitly contradicted himself by placing himself in the NBA commercial and removing the lines of his song that are critical of Nike and consumerism. Are all of these uses of art selling out, despite their differences? The rules for selling out are political, which in this case means empty rhetoric and posturing. I’m reminded of a dilemma I went through in the latter half of my high school years.

When I was 15 and 16, I was obsessed with punk rock music and the surrounding ‘scene.’ I read ‘zines (the punk rock version of magazines), went to shows, and even sported a Mohawk for a few months. Punk rock is especially applicable here because unlike most other music genres, by nature it is anti-establishment. This anti-authoritarianism also drives members of the punk rock scene to constantly scrutinize each other for selling out, which could consist of a band signing to wrong label, a writer not focusing on the right things, or a songwriter changing their sound at the wrong time. It may be driven by scene politics, but those were scene politics I cared about back then.

I had been staunchly ‘punk rock’ for years, refusing to listen to the ignant rap music almost all of my friends listened to or buy into their mindless consumerism (my words). However, I was growing tired of constantly posturing, and frankly, ignant rap music looked fun (it is). Towards the end of my junior year, I was at a skate shop with a friend, being an aimless teenager. I had been toying with the idea of beginning to dress more ‘normally’ for a few weeks, and that seemed like as good a time as any to pull the proverbial trigger on my thoughts. I walked up, picked out a pair of black and white Adidas Shell Toe sneakers, and began my transition into dressing much more like everyone else at my school. I got what I wanted: an easier time fitting in with the more popular crowds, compliments on the way that I dressed, and attention from the ladies (hey ladies!). I didn’t feel bad about abandoning my former stances because I felt I hadn’t. I still believed in them, even if I didn’t wear them like a billboard on my clothes. In a sense, I was becoming more mature and seeing the world with more depth. However, that didn’t lessen the sting of being voted ‘Most Changed’ in our high school yearbook. Nobody really saw the award as an insult or an embarrassment, but for me it was a quiet reminder of the compromises I’d made in my views.

Change is natural, even healthy. I’m not the only person who formerly or currently defines themselves by the music they listen to, via the subject matter of the music (or lack thereof). The music we listen to is emblematic of our worldview, whether that worldview focuses on the horrors of global capitalism or the beauty of local ass-shaking. When we’re young, we go further than choosing our music to fit our interests, we alter ourselves to fit the words and sentiments of the musicians we like. In the awkward confusion of post-adolescence, adhering to a genre of music can be more comforting than any home.

However, when we give so much of ourselves to our music, we tend to expect something in return. By pouring so much of our own identities into an artist, we feel that much more disillusionment when the artist changes and we no longer feel the same connection. Most basically, when our favorite artist sells out it makes us feel illegitimate and misguided, meaning we’ve been misled, and only the weak are misled. When our favorite artist sells out, it is us who is weak, not them. The social media age only intensifies this effect, because every post and tweet we made hyping an artist becomes a testament to our own gullibility.

The problem is, this isn’t how music and art works. The artist makes it, we consume it. Part of the reason people love artists like Macklemore is because he refuses to do what is expected of him. So why should we feel such personal disrespect when an artist does something we feel is questionable? Selling out tends to become a buzzword turned buzzsaw to cut down artists whose new direction we find distasteful. Macklemore suffers from this very problem, amplified through the intimate relationship he and Ryan Lewis cultivate with their fans.

In its original form, “Wings” tells the story of Macklemore’s relationship with sneakers. He has a hopeful beginning, a loss of faith in the middle, and a conviction at the end. However, we as a consumer pick out the pieces of the song that make the most sense in our lives and exclusively focus on those. In the case of “Wings,” those branding Macklemore a sellout identify most strongly with the anti-consumerist thought that “Phil Knight tricked us all.” The song is much more that that. It’s a human story (as only the best stories are) of contradiction and confusion, where Macklemore loves his sneaker but sees the evil they can be and are becoming. He is human, with human flaws, but has the courage to point out those flaws. His criticism is of our society’s commitment to consumerism, not of Nike or NBA specifically. He never changed his attire to Toms or even stopped wearing his Nikes, he only pointed out his own misgivings about what they’ve become. He definitely loves Nikes and probably loves the NBA, and who wouldn’t jump at the chance represent something you love?

I have my own reservations about “Wings” being used for the NBA All-Star weekend. I also have my own reservations about using the term sellout. Years of scrutinizing artist to make sure they are staying true to their stances while slowly slipping away from my own has a left a poor taste in my mouth surrounding the term. It unfairly reduces artists to statements and soundbites and cheapens the story they are trying to tell. The idea of selling out is rooted in the concept of authenticity and the conceit of hypocrisy. When an artist is labeled a sellout, it means they’ve contradicted a statement or stance they’ve made in the past, making them either a liar or a hypocrite. Everyone’s realized the redundancy of calling anyone a hypocrite; everyone contradict themselves all the time. It’s what makes us human, Homo sapiens. When we call Macklemore a sellout, in the end are we attacking the man who warned of being strangled by our laces, or the kid who put on a pair of Jordans and was elated to touch the net?