The orange awning and silver letters beckon as I cross the strip mall parking lot. I seldom wear face makeup and feel self-conscious as the automatic doors to Ulta Beauty swoosh open to unleash the blazing fluorescence within. The store’s bright lights and shiny floors illuminate my peeling lips and unpainted fingernails. This is not a makeup counter or a pop-up boutique. This space is at least four times the size of a drugstore cosmetics section. Standing before the legion of backlit displays, I feel crusty. Someone will know I don’t moisturize regularly. I feel out of place, much as I do when I enter a church: the pious will detect my blasphemy. No one here would say it in such biblical terms, but a question I found in a vintage beauty compendium called The Westmore Beauty Book seems to float in the air:

49. Do you accept the fact that homeliness

is virtually nothing more than a bad habit?

However, I have a $50 gift card from my mother, a well-intentioned reaction to the time we went to Ulta together and I didn’t buy anything. It’s much easier to power through uneasiness when you’re spending someone else’s money. So even though Ulta is a store that makes me feel like I should wear concealer and should not wear a bulky coat—Montana winter be damned—I’ve mustered the will to go a few times, dark circles brazenly uncovered, gift card in hand, in search of products that “meet my needs.”

Don’t get me wrong. I like makeup. Particularly glitter. But also metallic eyeliner, rhinestone body stickers, and eyeshadow palettes with bubbles of pigment frothing across their plastic cases. I once nearly bought a light purple lipstick because the color was named “Philosopher.” I liked the idea of the very body parts through which my philosophizing would pass being marked as scholarly by a lavender hue. But I already had a similar shade called “Lilac Mist,” so I refrained. Sometimes I cantilever my feet into heels so tall I can hardly walk to give presentations. All of which is to say that I like some superficial shit.

So I understand that going to Ulta can be fun. It’s supposed to be fun of the never-ending sort for the customer. The Ulta Beauty Code of Business Conduct calls this fun an offering of “unrivaled ways to be beautiful” and promises an environment conducive to “the thrill of exploration” and “the delight of discovery.” This is a sparkling way of saying that the store is gigantic, difficult to navigate, and filled with products you didn’t know existed for problems you didn’t know needed solving. Hundreds of hairbrushes, hung and shelved en masse above labels with redundant phrases such as “professional deluxe shine,” remind me of my own comb, a blue plastic relic that is probably meant for children. I unearthed it from my parents’ guest bathroom. The tremendous selection at Ulta includes brushes for dry hair and wet hair and hair in any state of dampness in between. There are brushes for cleaning your brushes. There is “The Twirler,” a pink-handled thermal brush with a poke-y ball of bristles. It looks like a softcore BDSM implement.

Unlike Sephora, a competing makeup powerhouse whose more limited brand selection, smaller stores, and crisp, black-and-white-striped aesthetic project an accessible elitism, Ulta is for all of us. Luxury and drugstore cosmetics coexist under one roof, sharing the same confusing floor plan. Dior mascara ($29.50 a tube) and My Burberry Blush Eau de Parfum ($60 an ounce) luxuriate only aisles away from Essence blush ($2.99) and Revlon tweezers ($3.49). The displays categorize some products by type and others by brand. The “Naturals” sign in the hair care section means “products for curly, thick, unrelaxed, anything-but-straight hair.” The “Naturals” sign in the skin care section means “probably contains some herbs.”

Question 74. Is your personal daintiness score beyond reproach?

Neither this more egalitarian approach nor the cheery salespeople, however, can shake my notion that Ulta demands a sleekness I lack. My unwashed hair glistens like some greasy beacon of my negligence. All the eyeliner I’ve applied without primer and all my years of sleeping with makeup on feel like secrets I must keep from the employees, whose “Can I help you find something?” chirps I rebuff. I have not reconciled my obsession with my appearance with my hunch that such vanity disenfranchises me. In Ulta the dissonance runs high; the specific joy of being surrounded by so much shimmer, gloss, and color to smear on my body contends with my revulsion at the rhetoric encasing the cosmetics. I sense that I’m in the presence of something unattainable.

Question 26. Do you know exactly what

make-up can and cannot do for you?

Ulta’s mission statement proclaims, “Every day we use the power of beauty to bring to life the possibilities that lie within each of us.” This pleasant, diluted language lands in a strategic sweet spot: the sentiment feels good to read, but its vagueness disburdens Ulta from accomplishing anything beyond peddling prettiness. Ulta’s aspiration to cultivate the potential of its customers, the majority of whom are women, is optimistic. Beauty does have measurable, gendered economic value. In the book Fat, Pretty, and Soon to Be Old, Kimberly Dark identifies this phenomenon and endorses “the savvy application of social knowledge.” She advises a reader who might curry favor in a job interview by wearing makeup to do it. Dark also acknowledges that these techniques are limited. They do not challenge the underlying system of straight-haired, small-nosed, light-skinned privilege. So even someone who manages her appearance immaculately, from the tightly wound curls on her head to the tailored cuffs of her pants, cannot control how other people perceive that appearance and make judgements upon it, racist, misogynist, or otherwise. Ulta and the marketing of its products ascribe real authority to beauty. But the power of pretty is only ever partial.

Question 19. Do you keep abreast of the developments in the world

of beauty—as well as the world in which you live?

It is not new, the yoking of a woman’s worth to her attractiveness. In 1956, my mother was born and the 252-page, male-authored Westmore Beauty Book was published with gems of advice like “there is almost no limit to what your face can do for you—or what you can do for your face.” Cosmetic companies still strive to increase your “face value,” except nowadays they co-opt social justice themes in the process. Once at Ulta, a display encouraged me to “JOIN THE REVOLUTION.” Which one? I wondered. On one hand we have what’s now called “the Fenty effect” of pop star Rihanna’s wildly popular makeup line, released in 2017, with more than forty shades of foundation formulated to actually work for women of color. After Fenty Beauty blew up, cosmetic companies that had never served darker skin tones suddenly expanded their offerings and diversified the models in their ads and packaging, too. On the other hand, many of these brands pivoted because they didn’t want to seem regressive and because so-called empowerment is trendy. This profitability explains the origins of the $30 Tarte “Dream Big” eyeshadow palette with colors like a pale pink called “Risk Taker,” a black called “Hustle,” a gold called “You Can,” and a beige called “Ambitious.”

Marketplace feminism is “more of a brand than an ethic,” as Andi Zeisler puts it. In an Ulta store, a woman has the right to choose. Among facial cleansers, that is. The IT Cosmetics display in Ulta is all about the individual who can join the movement with “game-changing” products that, “in the hands of real women everywhere, become life-changing. We believe you’re an IT Girl the moment you try IT.” The game being changed might only be that of wrinkles, but because a “real” woman’s beauty determines her value and that beauty depends on the appearance of youth, the wrinkle game does, in fact, have life-altering consequences. “That old women are repulsive,” Susan Sontag wrote almost fifty years ago, “is one of the most profound esthetic and erotic feelings in our culture.” To delay this undesirable but inevitable outcome, an independent woman (who, according to IT, is simultaneously a girl), can at last assert her worth and defend herself against the ravages of time by applying “anti-aging armour” such as “Confidence in a Cream.” Such a shield preserves that independent (read: affluent) woman by infantilizing her.

Question 9. When and if your beauty regime fails to produce the desired results,

can you truthfully say it is because of your need for more beauty

know-how and not because of a lack of persistence or willpower?

As teenagers sitting in my childhood bedroom, my best friend Johanna and I vowed that we were going to look like the pop singer Fergie in our thirties and Mrs. Lee, the mother of my first love, in our forties. We did not talk about how Fergie’s livelihood depends on how she looks, how a team of people spend their work week creating and maintaining her image, nor how she exercises like an elite athlete. Nor did we wonder how Mrs. Lee, who offered a realistic antidote to the fantasy of Fergie—or at least an example of the effects of decent genes and a fairly comfortable lifestyle—had ended up so elegant (code for “still beautiful.”) We were thirteen, for Christ’s sake. We’d fallen for what Sontag calls the “quixotic enterprise:” trying to maintain a girlish appearance even as the decades spin on. After all, an “IT Girl” strives to never lose her pedophilic appeal.

I started using eye cream in high school on the advice of my gorgeous thirty-something flute teacher. It felt like I was winning. I thought I’d figured out how to cheat the system, when all I’d done was succumb to it. With jars of “Advanced Night Repair Eye Synchronized Complex II” provided by my mother, I bowed early to the fear of aging. Nowadays I cheat time self-righteously with a glass jar of organic rosehip oil and shea butter eye cream from a small mountain town in Oregon. I feel as if I’m taking care of myself when I remember to apply the under-eye serum, but I’d be lying if I said I didn’t want to be pretty when I’m old. Knowing that this desire has been constructed within me does not make it go away.

Question 14. Do you realize that beauty today is more

often a question of know-how than money?

“Nothing so clearly indicates the fictional nature of this crisis,” writes Sontag, “than the fact that women who keep their youthful appearance the longest—women who lead unstrenuous, physically sheltered lives, who eat balanced meals, who can afford good medical care, who have few or no children—are those who feel the defeat of age most keenly.” Thus the women with the most access to anti-aging serums are also subject to additional pressure to preserve themselves and all the more disappointed and ashamed when their bodies, like those of every human, show outward signs of decay. Karma adherents, vision board enthusiasts, and cognitive behavior therapy advocates might posit that when Johanna and I made the Fergie pact, this intention was enough to nudge the universe toward its manifestation. Cosmetic rhetoric would have us believe that she and I are responsible for how we look as we age, as though character determines appearance and the money we spend, the genes we inherit, the trauma we accumulate, the pollution we endure, and the marginalization we survive all have no bearing on whether we arrive at old age haggard or glowing.

Question 11. Do you accept the need to look, think, act and feel like a

beauty if you wish to be accepted as a true beauty?

“Let me know if you have any questions!” at least one salesperson trills when I wander through an Ulta. I have so many, I think. What distinguishes “Girl Boss” fake eyelashes from “Center of Attention” fake eyelashes? How did the “Take me back to Brazil Rio Edition” eyeshadow palette, with a warning that reads “PRESSED PIGMENT SHADOWS ARE NOT INTENDED FOR USE AROUND IMMEDIATE EYE AREA,” make it to market? Who thought it was a good idea to name a brown eyeshadow “Cat Call” or include in the Urban Decay “Vice” line of lipsticks a shade of pink called “Violate”?

People who work in makeup stores tend to be friendly. They dispense compliments freely. They have to be this way, so that customers feel comfortable sharing their insecurities aloud. But the conversation I imagine we would have exhausts me. If I were to engage with one of the employees, we’d have to talk about endocrine disruptors and how I’m trying, with limited success, not to put them on my body. Ingredient scrutiny is trendy, so more cosmetic packaging than ever highlights what’s not there, much like food labels. But there are still so many legal and prevalent hormone-interfering, environmentally damaging additives: BHA and BHT; triclosan; polyethylene glycol; siloxanes; parfum or “fragrance”; petrolatum/mineral oil; sodium lauryl sulfate; methyl, propyl, ethyl, or butyl parabens; the anolamine family (DEA, TEA, and MEA); phthalates… and so on. The list is too long. It’s difficult to remember. And while these ingredients do little immediate damage, they can accumulate and wreak havoc later on, in the form of cancer or infertility. Significant intellectual burden falls on the consumer who doesn’t want to slowly poison herself.

Question 21. Do you know your own face-type—in terms of beauty?

After the litany of ingredients to avoid, I’d explain that I’m prone to rashes. During a Sephora makeover in college, the stylist rubbed a moisturizer ‘for sensitive skin’ on my face. It stung like hell. Once at a Macy’s brow bar as a tween (during an appointment my mother had sprung on me), the esthetician, after ripping out a flock of hairs, put a serum on my forehead to alleviate incipient redness. I wore a swath of supernovae acne for a week.

Then—back at Ulta—I’d have to say that I do not want cleanser, foundation, face powder, toner, astringents, blush, bronzer, primer, acne treatment, concealer, or setting spray. I have what the brand Philosophy calls “makeup-optional skin,” which their “Purity Made Simple Moisturizer” promises to produce in just three days, as if all skin were not intrinsically makeup-optional. Feminine beauty, Ann J. Cahill writes, “far from being something natural or innate, is a state to be striven for, a state that takes planning, careful work, and a significant investment of time.” Granted, my unblemished, light, and relatively young skin still adheres to conventional beauty standards. But the dominant face makeup narrative insists that all faces, including mine, need fixing: color-correction, shine elimination, pore reduction, fine-line smoothing, and perhaps a Tarte primer called “BLUR.” No matter that the second ingredient after water in the “Purity Made Simple Moisturizer” is cyclopentasiloxane. The Environment Canada Domestic Substance List classifies cyclopentasiloxane as “expected to be toxic or harmful” and “suspected to be an environmental toxin and bio-accumulative.” Purity, after all, is in the eye of the beholder. Though Purity Made Simple Moisturizer, were it in your eye, would probably cause a burning sensation.

Question 1. Are you more attractive and more beautifully

groomed today than you were five years ago?

I’ve been to Ulta seven times in my life. Three of those times I’ve left empty-handed and too overwhelmed to buy anything. Once I bought a “third-eye” face mask to mail to my hippie cousin and coconut milk face wash for myself that made my cheeks soft for a few days before it started causing dry patches. Another time, enabled by the sparkly pink gift card, I got a hemp bath bomb, some NYX “Hella Fine” liquid eyeliner, a collagen-infused marine sponge, and a jade face roller—because when healthcare isn’t universal, self-care can pretend to be. Whether it involves rubbing your cheeks with a stone or smoothing overpriced lotion on your forehead, a so-called “skin care routine” can help people to stay familiar with themselves, to feel the reality of their physical bodies. Maybe this kind of self-knowledge is the “power of beauty” that Ulta seeks to harness. Or not.

The idea that looking good feels good and feeling good looks good is fraught. Once, when I was 23, in an athleticwear store aimed at women, I tried on a teal swimsuit top.

“It fits you great, honey,” my mom said when I showed her.

“Yeah?” I smiled.

I closed the dressing room door and looked in the mirror again. The band compressed my ribcage. The straps dug into my shoulders. I felt squeezed. But it looked good. Cahill writes that the pleasure of feminine beautification is beneficial and feminist only if it is “distinguishable from the demands that patriarchal society places on female bodies.” The incongruity between my appearance—hot—and my sensations—too tight—was overwhelming. I started crying, quietly.

Question 98. Do you know the beauty value

of a smile and a pleasant disposition?

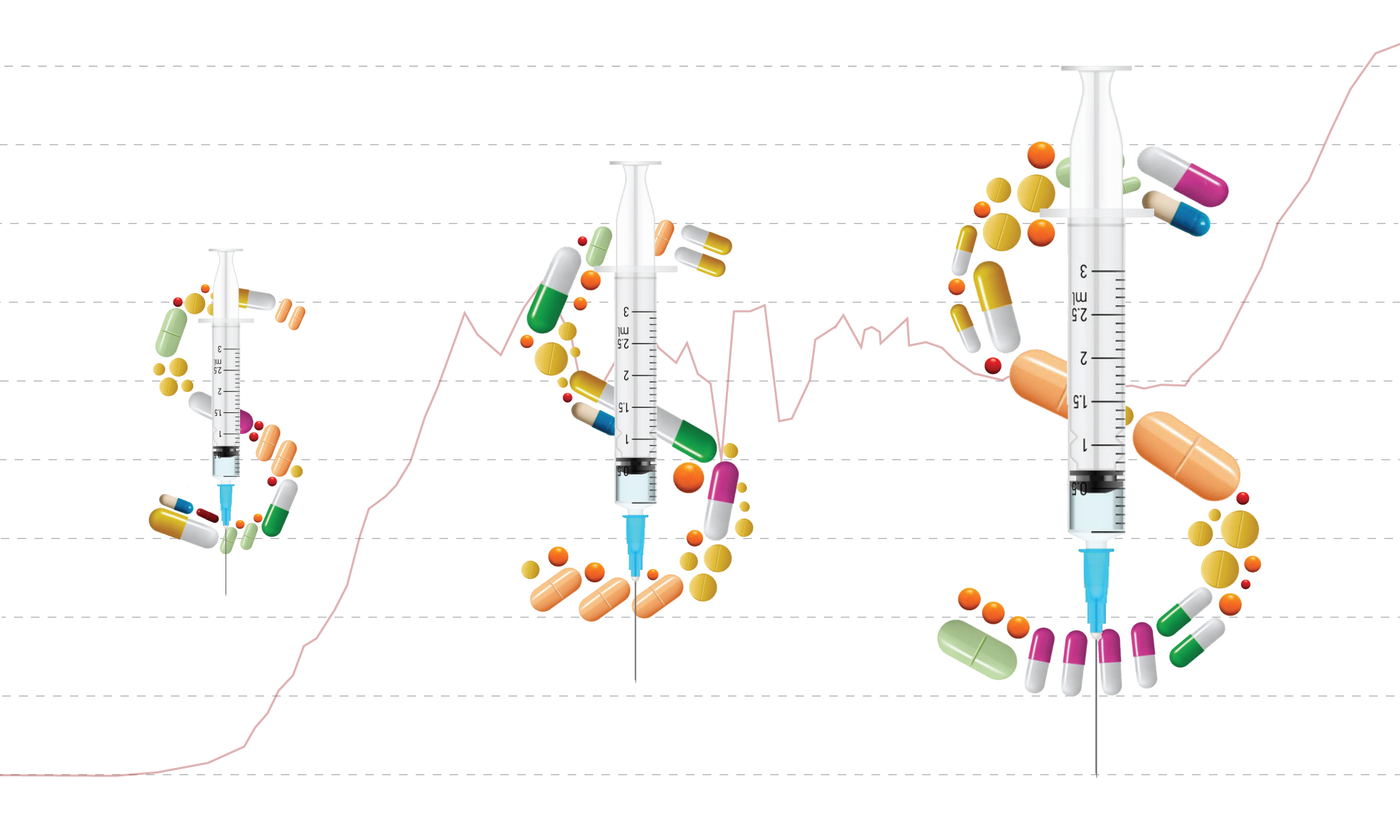

I know that palatable can be safer. Prettiness is a social lubricant, a waived speeding ticket, a salary bonus. What Baudelaire wrote more than a century ago about a woman’s duties—“she is obliged to adorn herself in order to be adored”—remains true. Ulta makes me uncomfortable because beauty is both a site of resistance and a site of repression, where the tools of drag performance and body affirmation in other hands can be magnifiers of self-hatred and pressure to conform. And Ulta doesn’t seem very interested in acknowledging that challenge. Instead Ulta’s feminism is comfortable, safe, and fun. It’s apolitical and neo-liberal. In this context, women liberate themselves by their individual choices and through full participation in free market capitalism. And feminism based on consumer purchases is wildly successful, to the tune of $6.71 billion in 2019. In her 1990 book The Beauty Myth, Naomi Wolf calls this corporate income “capital made out of unconscious anxieties.”

It is tempting to curse fashion and beauty as frivolous pursuits that, as Jacki Willson explains in Being Gorgeous, trap women in their images and exclude them from politics. But the problem does not lie in the desire to find the best highlighter for your complexion. The problem is that “the mask is the woman.” No wonder, then, that going into Ulta is unsettling: the entire enterprise is dedicated to the fact that my appearance is inextricable from my value as a person. In this context neither wearing makeup nor abstaining from it are without repercussions. The age-old damned if you do, damned if you don’t paradox. As long as it remains lucrative to foster insecurity, I will feel surveilled under the bright lights of Ulta. I will still sense, in that store, that I am in the presence of something unattainable. My fully realized, beautiful (and therefore wealthy) self can never come into being. She will never be satisfied. And Ulta will be there to assuage and perpetuate that inadequacy.

“Your real beauty inspires me!” reads a quote from IT Cosmetics CEO Jamie Kern Lima alongside before and after photos of her with and without makeup. “Real” beauty as an inherent trait only waiting to be unveiled—a process of revelation that ironically occurs through covering the face with creams, powders, and pigments—is the mission of the Too Faced line of foundations called “Born This Way.” The pursuit of “real” is also the goal of the hair-care brand Bed Head. Their extensive product line implies that this “natural” state cannot be achieved without synthetic intervention. And as it’s presented by these snippets of marketing copy, the idea that our authentic selves are accessible only through artifice is a gimmick to sell products. Yet there’s a path toward liberation intertwined in that concept, if through artifice I shed light on my irrepressible self.

One of my former roommates threw parties for Purim, a carnivalesque Jewish holiday where revelers are encouraged to drink alcohol, make nonsense speeches, and wear masks, or as she liked to say, partake in gender anarchy. To prepare for our 2019 festivities, I stopped at a barbershop for an undercut, leaving with the hair between the nape of my neck and my ponytail buzzed. At home I realized the full ensemble, sliding in rhinestone earrings long enough to brush my shoulders and wiggling my feet into silver stilettos. Along my eyelids I glued giant, bejeweled fake eyelashes; across my cheeks I dusted the fancy glitter (Fenty Diamond Bomb, if you must know). And above my lips—reddened with a color named “New Temptation”—I used the liquid eyeliner from Ulta to draw a curled, mosaic Salvador-Dali-esque mustache.

***

In July 2020, Ulta unveiled its “Conscious Beauty at Ulta Beauty” initiative, following in the footsteps of “Clean at Sephora” with a “Clean at Ulta Beauty” distinction based on an extensive list of “made-without” ingredients. Ulta has also begun identifying and grouping products that are sustainably packaged, vegan, and/or cruelty-free. I haven’t been inside an Ulta store in more than a year; I don’t know how these changes have affected the in-person shopping experience. I do know that in November 2020, when I finally got around to spending a second gift card from my mother (“I thought you liked that store!” she complained), the online version of Conscious Beauty was difficult to use. It’s not yet possible to filter a product search by sustainable packaging, for instance. Instead there are long lists of brands in each category. One of these did lead me to a recycled-plastic tube of reef-safe Kinship sunscreen, but I soon grew tired of inefficient scrolling and inconsistent ingredient labels and selected the remaining items based on colors and glitter content.

In the months to come I imagine that in-store Ulta staff will hang freshly printed signs, rearrange accordingly, and set up new displays. Employees’ knowledge of product specifications will become even more encyclopedic, if they’re particularly dedicated, or they’ll reach the same threshold I did and give up on cataloguing so much information. The Westmore Beauty Book asks,

7. Is your individual beauty plan in keeping

with your personality and way of life?

But there’s no way to square an individual plan with the fundamentally overwhelming nature of an Ulta Beauty store, in part because organizing thousands of cosmetics is a daunting task, and partly because I’m no longer sure it is worthwhile to curate an approach to beauty that communicates my personhood. I love flashy makeup. I would prefer not to get cancer. I also value consumer literacy, want plastic-free packaging, and wish deeply for better regulation. Conscious Beauty sounds like a product that will “meet my needs.” I know it won’t. ▩