Tommaso Pellegrino was seven years old when he went through the ice. He had slipped quietly away from the rambunctious children sliding, gliding, lurching, and tumbling alongside their parents on the lake’s stubbled surface. He had paused for the briefest moment to take in the scene, then with sibylline grace simply vanished.

Old for the first grade, Tommaso was slender and short, with loose dark curls and blue eyes, fair skin and red lips—from his mother. He lived with his parents in the junior faculty housing by the lake.

Tommaso’s father Paulo was a cosmologist at the particle physics lab on campus. Paulo was often away from home. Monday mornings, effervescently kissing his children good-bye, grandly swinging his briefcase, he strolled to the rail depot, only a half mile from the apartment. He rode the shuttle to the junction, boarded a train to the city, and there hopped a bus to the Brookhaven National Laboratory on Long Island. He returned home in the evenings on Thursday.

While Paulo was away, Tommaso’s mother Juliana cared for Tommaso and his baby sister, Christiana. Juliana hailed from Bolzano at the base of the Tyrolean Alps in northern Italy. She possessed creamy skin and luxuriant blonde hair that she wore long and hanging nearly to the base of her spine in a pony tail or sometimes, adorably, Teutonically, in twin braids.

I taught at the elementary school where Tommaso was a student in my first-grade class. Male elementary school teachers were of course not common. Not then. Not now. The principal perhaps. The gym teacher. Maybe the art teacher. But only rarely a classroom teacher. It was not so much because of some institutional sense of custom or decorum. Honestly, it was probably more a lack of interest from men in the work, a prevailing awkwardness and discomfort in relating to first and second graders. And in the background, I imagine there was also a belief that men were insufficiently nurturing.

Nurturing was not an issue for me. I was unassuming and calm, organized and orderly. A good listener. Patient. I had learned to appreciate the value of shaping and holding generous space for the kids, establishing boundaries both expansive and firm.

But the messy truth is that I was also there for the mothers.

The first day of school of Tommaso’s first grade year, the other students, many of whom knew each other from kindergarten, bounced animatedly off each other, a hive of undifferentiated energy. Tommaso had arrived from Italy with his parents earlier that summer. He stood apart, appraising and watchful.

Tommaso packed a Theodore Tugboat lunchbox and talked volubly to his classmates about Theodore’s adventures with rest of the Big Harbour gang. He told me, more than once, about his preference for things that floated and aversion to things that sank. And honestly, that pretty much summed up his personality. In our class, he was the buoyant student, the unsinkable presence, a safe harbor for the rest of us. Including me.

Tommaso arrived by bus most mornings, but his mother often retrieved him at the end of the school day, particularly when it had been raining. Juliana’s English was good, nearly unaccented. But she appeared sad to me. She told me the apartment building where they lived was drab and lonely. She had not met other mothers. People were not friendly.

Her husband Paulo had grown up in Milan, she told me, but she came from picturesque and prosperous Bolzano. She had been a competitive figure skater as a child, I learned, but had happily put the skating behind her when she went to university, where she met Paulo.

In late October, we studied water—its properties, its uses, its significance for humans and other living creatures. I organized a field trip to visit the lake and the canal that flowed alongside it. Several mothers accompanied me to assist with the children, one of whom was Tommaso’s mother. She brought Christiana in the stroller.

The bus parked by the football stadium. We herded the students down the hill. It was a warm and glorious autumn day, the moist air saturated with light, the leaves stippled with faint drops, reflecting the emerging colors: rusts and golds and magentas.

I held Tommaso’s hand. Elise, who had become his closest friend, skipped happily just ahead, laughing for him to follow. Tommaso’s mother pushed the stroller on the other side of Tommaso, clasping his other hand. He too skipped along, chortling, his blue and red Theodore Tugboat backpack jostling happily on the thin blades of his shoulders. Juliana and I pulled him into the air, retrieving him to us.

Tommaso stopped to point at a blank, featureless tower planted on the crest of the hill. “That’s the physics building!” he shouted to Elise, who winced and pressed her palms to her ears. “Papa works there. He makes hot soup and then pours it into in a black hole!”

Juliana glanced at me and rolled her eyes. “Paulo’s a particle physicist.”

We descended to the lake. Juliana nodded across the road to where twin brick apartment buildings, each rising five stories, fronted the lake. “That’s Ribben and Magpie,” she said. “We live in Ribben.” She stared pensively at the buildings, which even in the golden light seated themselves heavily atop the earth, like unquiet tombs. “Our apartment faces away from the lake,” she added.

“Magpie’s a bird,” Tommaso confided, proud of his English.

“Yes,” I said. “And Ribben?”

Tommaso pressed his lips together and furrowed his brow. “Ribben’s a cold monster,” he said.

We reached the lake and marched on to the bridge toward the canal. Tommaso waved across the road at his apartment. “Hello Ribben. Hello Magpie.”

“Hello Baggy Pie,” Elise echoed. The children shrieked with laughter.

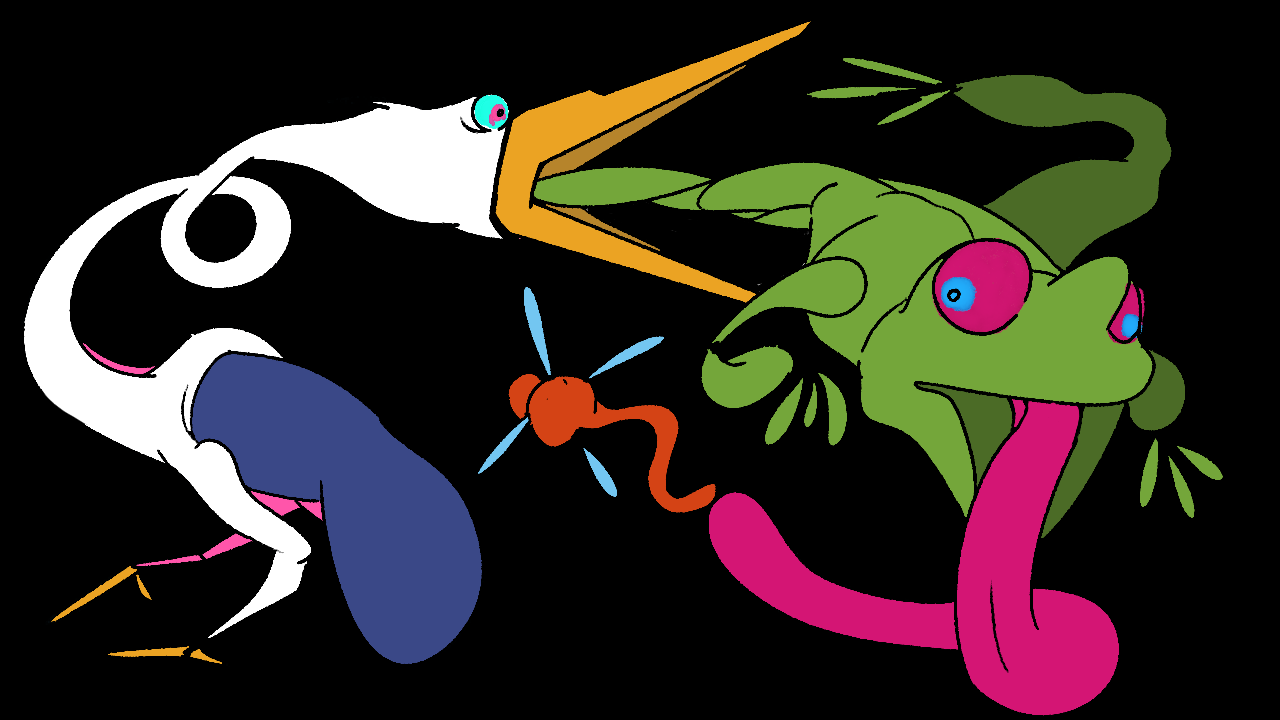

As we approached the lake, rowers swept by, gliding rhythmically through the serene water, clockwork dip and pull of the oars. The children were entranced by the tiny men and women perched in the stern, baseball caps flipped backwards on their heads, bullhorns pressed to their lips, counting out the beat, barking commands to the rowers.

Power 10 in two. One! Two! Square! Touch It Up!

We marched across an arched stone bridge spanning the lake and turned on to the far bank. Tommaso was telling Elise about the previous winter, when the lake had frozen solid for 10 days and Tommaso’s mother taught him to skate. He moved his arms in a synchronized, pendular motion in front of him while sliding his legs behind him like scissors snapping. “Swoosh Swish Slice / Swoosh Swish Slice,” he chanted. “That’s how Mama told me to skate.”

Tommaso turned on his heels and for a moment stared gravely at the canal on the other side of the towpath. I pivoted with Tommaso and, perhaps like him, found myself imagining the glassy surface itself to be a solid that would bear my weight if only I dared to test it, to trust it.

“Mama said I should never ever skate on the canal,” Tommaso whispered to Elise. “She said the water doesn’t get cold enough. The ice looks safe because it’s smooth. But she said smooth ice isn’t strong. It cracks!” He turned back to the lake and waved his arm panoramically. “Over here, the ice on the lake is rough. Mama says rough ice is safer.” Then he frowned.

“When we work on the land and on nature and change it, that’s called engineering,” I told the kids, sitting on blankets and eating sandwiches, a few minutes later. “Engineering is something people can do that most other animals cannot, at least not in the same way. We change the natural world to adjust it and bend it to our human needs. Or what we imagine those needs to be.”

More than 150 years ago, I told the children—now seated on blankets and eating sandwiches—workers from Ireland came to America and dug this 60 miles canal with hand tools like picks and shovels. I said, “Imagine if our principal, Miss Pigeon—” and had to pause here because the students always laughed at the name of the principal.

Starting up again, “Imagine if Miss Pigeon said to all of you, ‘Children of the first grade, there you are at the canal, almost two miles from our school. I am giving each of you a spoon, knife, and fork from the cafeteria. You must dig a ditch two feet wide and two inches deep from the canal to your classroom.’ What would you say to that?”

The students oohed and aahed, because of course this task appeared unfathomably difficult.

The qualities that made me a good teacher for young children also made me attractive to their mothers, and to girls and women generally, and oddly, for similar reasons. I packaged a stabilizing calm, stillness, and warmth within a strong and graceful physique. This combination—creating space, promising safety, harmonizing gentleness and strength—turned out to be pretty irresistible.

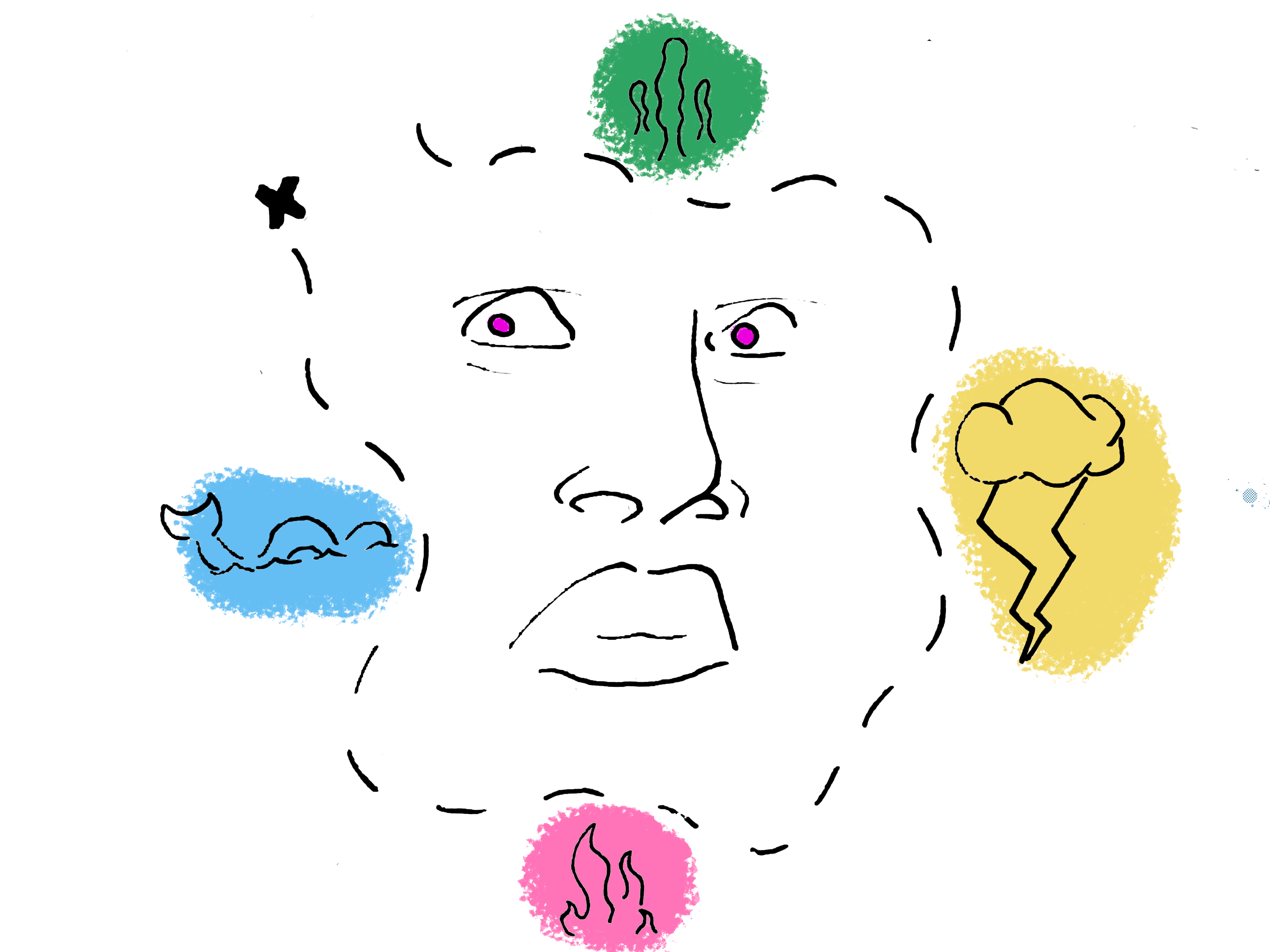

I was not classically handsome. Far from it. As a young teen, I suffered a devastating series of bouts with acne that permanently scarred my face, leaving it rough and pitted like the mountains of the moon. Craterface, my schoolmates called me. Indeed I was.

But while this disfigurement might have produced a corresponding layer of emotional scarring in other adolescents, I’d arrived at this moment of peril fortified with a lavishly secure childhood that somehow secured me from the devastation that this pox stamped upon others. Of course, I knew objectively that the acne scars were hideous, but I was nonetheless, without effort, able to accept these cracks and holes in my face as an unthreatening texture.

In spite of my cratered visage, or perhaps even partly because of it, females were drawn to me. My gentle and passive receptivity to whatever interior emotional needs they wanted to project on to me seemed a kind of vacuum of the sort nature abhors, and so a strange attractor for female affection and ardor. This pattern was so familiar and natural to me that at the time I graduated college and departed for Europe in the early 1990s with my girlfriend Miranda, I took for granted and navigated comfortably the potentially complex relationship dynamics that sometimes ensued.

Miranda was British. We spent several months in Oxford, then hopscotched to Paris, Paros, Prague, and Vienna. By the time we settled in Berlin—where for a year we partied like it was 1995 and I obtained a sinecure at the Goethe Institute as a teaching assistant—Miranda had become used to the attention I received from other women. She understood this attention was the current in which I swam, and, indeed, she perceived more clearly than most that this piece of my identity did not make me a threat to her and to our relationship.

Then Giselle entered my life. A fellow assistant at the Goethe Institute, a few years older than me, Giselle had until 1989 lived on the eastern side of the Berlin Wall, and she subsequently staggered into West Berlin striped by Soviet-bloc-sized emotional wounds for which I was entirely unprepared.

I suppose she was malformed as a child by surveillance, suspicion, paranoia. It was easy for me in retrospect to imagine how the sensory maelstrom that was Berlin in the 1990s might quite easily have fragmented and dissolved what I took to be the slipshod fabrications of her mind.

With an unmediated urgency that I’d never before experienced with anyone, she latched on to me as if I were a life-preserver tossed to her drowning, flailing, sinking self. She would not yield, her emotional need subtracting fully the space that I—instinctively and without forethought—created for women, subdividing and zeroing it out until I found that I myself could not breathe. She wanted me in every conceivable way.

I needn’t divulge details. What would be the point? The only point, in the end, was that lacking me confirmed to Giselle that she lacked everything, that she would always be partial, emptying, never whole, always broken. And so one moist evening, drunk to a point of no return, she stepped in front of a train.

A hard lesson for an innocent kid, as I somehow still imagined myself to be (although I was 23 years old, nearly 24). My response was to flee. From Berlin. From Miranda. From myself. My unarmored grace now exposed to me as a dangerous ugliness no less grim and diminishing than my pocked flesh, which for the first time also horrified and repelled me.

After a few months back in the States with my parents, I joined the Peace Corps and was sent to a village outpost in Zambia’s Luangwa Valley. There I spent two years teaching primary school —and learned I had a knack for the classroom.

My beautiful, smiling, exuberant young charges, in their powder-blue school uniforms, called me Teacher and would not quit me. The change of scene—dry heat and clear skies and empty spaces—quite restored my calm, and my students explored me like a topographical map, as if my body were itself their textbook.

Swarming, they clambered and crawled upon me, touching my face, probing its bumps and colors as if it were indeed the surface of the moon, stroking my eyes, my ears, my lips, entangling their fingers in my hair (which had grown long and thickened with curls), tenderly tracing the line of my jaw and the stubble of my chin, testing the strength of my biceps, grasping and pulling at my fingers.

“You are a strong-quiet man,” they told me.

It was also there, in my classroom in my village in Zambia, that I first encountered the mothers. Well, one mother in particular. Her daughter was Ayanda. Her name was Thandi. I became her confidant and confessor, her friend and companion. There was nothing profound about our relationship. Thandi certainly wanted nothing more from me than I was prepared to give. Unlike with Giselle, I did not represent rescue or a way out.

From a distance, I realize now that we were a triangle, Ayanda the necessary bridge for Thani and my connection. We bonded from conversations about her daughter, sharing insights, discussing goals and prospects, devising paths forward toward imagined futures for the daughter, these also images of possibility for Thandi herself.

Throughout, I remained still. I allowed Thandi to claim me, to inhabit me, to want me. We together shared and loved something precious. Her daughter. Which somehow sanctioned our gentle, exquisite, private lovemaking.

The rain returned fell intensifying ardor in November, hardening into an unyielding sleet by December. The grownups fretted, of course, descending into cycles of negative speculation about what it all meant, the weather, as always the screen on which they projected their own anxieties.

But the children were resilient, unflappable even. Protectively wrapped, like mini-Michelin men and women, they bounced and careened and caromed into my classroom each morning with the earnest exuberance of the un-dammed. Carelessly and without heed, spirits buoyant, cheeks rosy, noses runny, they unspooled themselves from their hats, scarves, coats, mittens, and boots, shaking away the water like drenched pups, as if this heinous weather were absolutely normal, as indeed it may well have been for them, for what else did they know?

One morning in December, Tommaso marched from the cloakroom into the classroom, steam rising like smoke from his thick mop of dark curls. He approached my desk, bright-eyed, smiling incandescently. “Because it’s so wet, I am bringing one of my Theodore Tugboat books for you to read,” he announced. “It’s called Theodore and the Stormy Day.”

Juliana trailed behind Tommaso, in woolen tights, skirt, and sweater, her hair unbraided. She looked pale and exhausted. She offered me one of her own wan smiles.

The relentless rain had made their apartment unbearable, and after Thanksgiving, she and Paulo had agreed to hire a babysitter for Christiana and she’d taken to bringing Tommaso to school herself in the mornings, remaining until the end of the school day as a parent helper in the classroom.

When the students went to lunch, Juliana often joined me at my desk. We ate and talked. On this particular day, with the lights off and the room a cloistered and intimate shadow of itself, she told me of her deteriorating relationship with Paulo and its impact on Tommaso. “He’s such a happy boy, in his nature,” she said. “But he notices and he knows and it unsettles him, that somehow he might have to choose.” I chewed my food thoughtfully, my eyes locked on hers.

Juliana told me about Paulo’s second life at Brookhaven. “His half-life, he calls it,” she said mockingly. “He has relationships with women in this other life. He does not conceal them. He never has.”

Juliana elaborated. She said Paulo believed that the universe bends back upon, splits, and refracts itself. That we inhabit multiple alternative realities, each a portion of a larger plenitude. Each with its own emotional and physical claims. “Tommaso adores his father,” she said. “He says that one day he will join Paulo in his half-life and explore with him the mysteries of the universe.”

I suggested to Juliana that maybe she should consider her own second life, that she didn’t need to fully tether herself to Paulo. For a moment, the weight she carried lifted, as she pondered what that might look like. Her long fingers languidly kneaded the papers on the desk then curled themselves into the palm of her hand, as if seeking within its cartography something to touch and hold that belonged only to her.

Her knee pressed against mine. “It’s true,” she said. “Maybe it’s time for me to teach skating again.”

We stood to prepare the classroom for the return of the children from their lunch. Juliana took my hands and wrapped them around her waist and rested her head on my shoulder. “Thank you,” she murmured. “You are a good man. A good teacher. Tommaso adores you, too.” Tilting her face up toward me, she raised up on her toes and laughed, gently rubbing her nose against mine. Her fingers explored the bumps and grooves of my face. “Such a rough surface,” she said wondrously. “So many places to hide.”

She called me two days later. I was waiting for her call. Tommaso had been absent from school. He wasn’t sick, she said. But he had been having night terrors. He refused to go to school. He wouldn’t leave her side. He clung to her like a baby kangaroo. “I’m your baby kangaroo,” he kept saying. “Please let me stay in your pocket.”

Ribben was indeed a cold monster I thought as I stepped into the narrow lobby, really just some silver mailboxes, bolted to the dirty brown brick façade, adjacent to a sad plastic Christmas tree and a small, non-operating elevator. I climbed the stairs to the third floor and found the apartment at the end of a glowering corridor.

“What are you doing here?” Tommaso said, tugging at his forelock, staring at me as if I were a space alien. He clutched a toy boat in his hand but looked disheveled and slightly dazed. Without waiting for me to answer, and with no welcome in his voice, he shouted to his mother, “Mama, it’s Teacher.” Then to me, sotto voce, his voice chill and precise. “Go away, Teacher. Stay away. You’re ugly. You scare me.”

That was my fantasy, as I knocked on the door to the apartment, and I stifled an instinct, once more, to flee. But when the door opened, Juliana stood there alone, wiping her hands on a rag, smiling. She wore jeans and an Icelandic sweater, her hair fetchingly pulled back beneath a blue bandana. “Thank you for coming here,” she said. “I know it’s a lot to ask.”

She’d made prior arrangements. It was a Thursday. It would be late in the evening before Paulo returned from Brookhaven. Tommaso would play at Elise’s house for two hours.

Juliana took my wet coat and scarf and tousled my hair. “Here, sit.” She led me by the hand to the worn couch, its cushions collapsing into themselves, and I sank down into its vortex.

I took in the room, which was carpeted and rectangular, the narrow side framed by a single window that faced a skeletal grove of trees lashed by the wind and the rain. Low bookcases lined the walls across from me crammed with physics texts and works of popular science and literature. Above the books, framed photos lined the wall—Tommaso holding Christiana, Tommaso’s school photo, the entire family, Juliana on the ice. Toys littered the dingy, carpeted floor—Tommaso’s boats, his Legos, an Etch a Sketch, a tangram puzzle, an N64 plugged into the television.

“That’s one busy boy,” I said.

Juliana smiled and nodded. “Too busy.” She handed me a cup of tea and settled into the sofa beside me. “Christiana’s napping,” she said.

She laid a crocheted blanket across our laps. She leaned into me and shivered. “You see? About the damp and the cold?”

“It’s not so bad.” I actually rarely experienced cold. “Tell me about Tommaso,” I said.

She sighed. “Two nights ago, he climbed into bed with me. He was shaking. Sweating. Cold sweats. He said he’d dreamed about a rocket ship that smashed into the earth, cracking it open. Paulo and I were on one side of the crack. Tommaso was alone on the other side.”

I took her hand, pressing it between both of my own, gently stroking the skin between her thumb and forefinger. I gazed quietly into her eyes, holding her gaze, liquefying the boundary between us.

“He was terrified,” she said. Her eyes pooled, and as they did, I could feel myself emptying, opening up, allowing her tears and her pain to fill and inhabit me.

“Younger children, they are not aware,” she said haltingly. “But as I told you, Tommaso, he is seven, he is old for his grade. But he also old for his age. He sees everything.”

“What does the crack mean?” I murmured.

She didn’t answer. Instead, her cheeks glistening, her eyes now closing, she kissed me, her warm mouth parting, and I could feel the dam breaking.

We waded into the new year, damp and bedraggled. Then in mid-January it all ceased. The skies cleared. The air dried. The temperature plunged. And one morning the children awakened to a miracle. The sun shone gloriously and with crystalline splendor upon our little patch of earth, unveiling a winter wonderland.

I’d been told snow days in the town were the high point of every year, a liminal state of joy and possibility where children, and indeed the entire town—shedding all rules and routines scaffolding their lives—converged upon the lake, clambered on to the ice, and there commenced a singular extravaganza, long known to all in the community as Ice Follies.

I sat atop the protruding root system of a willow, on the strip of land separating the lake from the canal, lacing my second-hand skates, taking in the scene, hundreds of children, their parents in tow, cantering and skidding upon the frozen lake.Kids playing hockey, racing each other, dancing, staggering, falling, lifting themselves up, all sparkling with a sun-kissed diamantine splendor.

At the center of the crowd, I spotted Tommaso, bundled from head to toe, skating in circles around a man in street shoes pushing a stroller across the ice. I recognized him from the apartment photos, of course. Paulo Pellegrino, a short, smiling fellow wearing smart-looking leather gloves and a pea coat. I didn’t see Juliana. I sauntered on to the ice myself, trying to appear more confident and composed than I felt. “Teacher!” Tommaso shouted when he saw me.

Tommaso was a natural, skating smoothly and in rhythm toward me—swoosh swish—while I hobbled lamely across the ice, my skates strapped like bear traps around my jellied ankles. Approaching at perilous speed, he dug in his right blade, pivoted and spun to a stop beside me, showering me with snow. I reached out to grab him for balance.

In that moment Juliana swept by on her skates, laughing. “You are like the drunken sailor doing the random walk,” she shouted. She spread her arms and lifted one leg high behind her. Tilting forward, she spun lazy eights in the ice while Paulo neared with the stroller. Just before he reached us, Juliana began skating in earnest again, with short and powerful strokes, carving several tight circles around us before pulling up short next to her son. She was breathing lightly, her face aglow. She touched her husband’s arm.

“Paulo, this is Tommaso’s teacher, you’ve heard so much about.”

Paulo peered curiously at me, his dark eyes merry, flickering beacons behind wire-rimmed glasses. Luxuriant curls poured floridly to his shoulders beneath a black watch cap. He was quite short, but very handsome, his posture a pugnacious assertion of self-regard.

“So we finally meet!” He shook my hand warmly. “Tommo and Julia speak so much of you. It’s as if we share in the same family!”

Did alarm bells peal? Did the hackles rise? Not really. Not for me. I was not that sort of person. I’d continued to spend time with Juliana in the classroom. When Paulo was at Brookhaven, she’d arrange play dates for Tommaso and babysitting for Christiana so she could see me alone. She’d been clear that Paulo would have no clue. “He’s too self-absorbed,” she said. “He orbits around himself.”

But now I wonder.

What I remember from that moment when Paulo and I faced each other on the ice, shaking hands, talking informally, about nothing really—what did I think of Ice Follies, his commute, platitudes about his family, an off-handed reference to his “half-life”—what I remember now is the warmth, bordering on heat, that this proximity generated, as if some force field had been created.

Paulo chattered away. Juliana, hovering in the background, arched an eyebrow meaningfully for my sake, then whispered something to Tommaso, kissed him on the top of his head, and skated toward the center of the lake.

Meantime, Tommaso had begun to tug on his father’s coat sleeve, pointing to the shore. “Papa, this is where Teacher brought my class. Do you remember?

Paulo idly pushed the stroller forwards and backwards, oblivious to Tommaso, absorbed by the sound of his own words, directed at me.

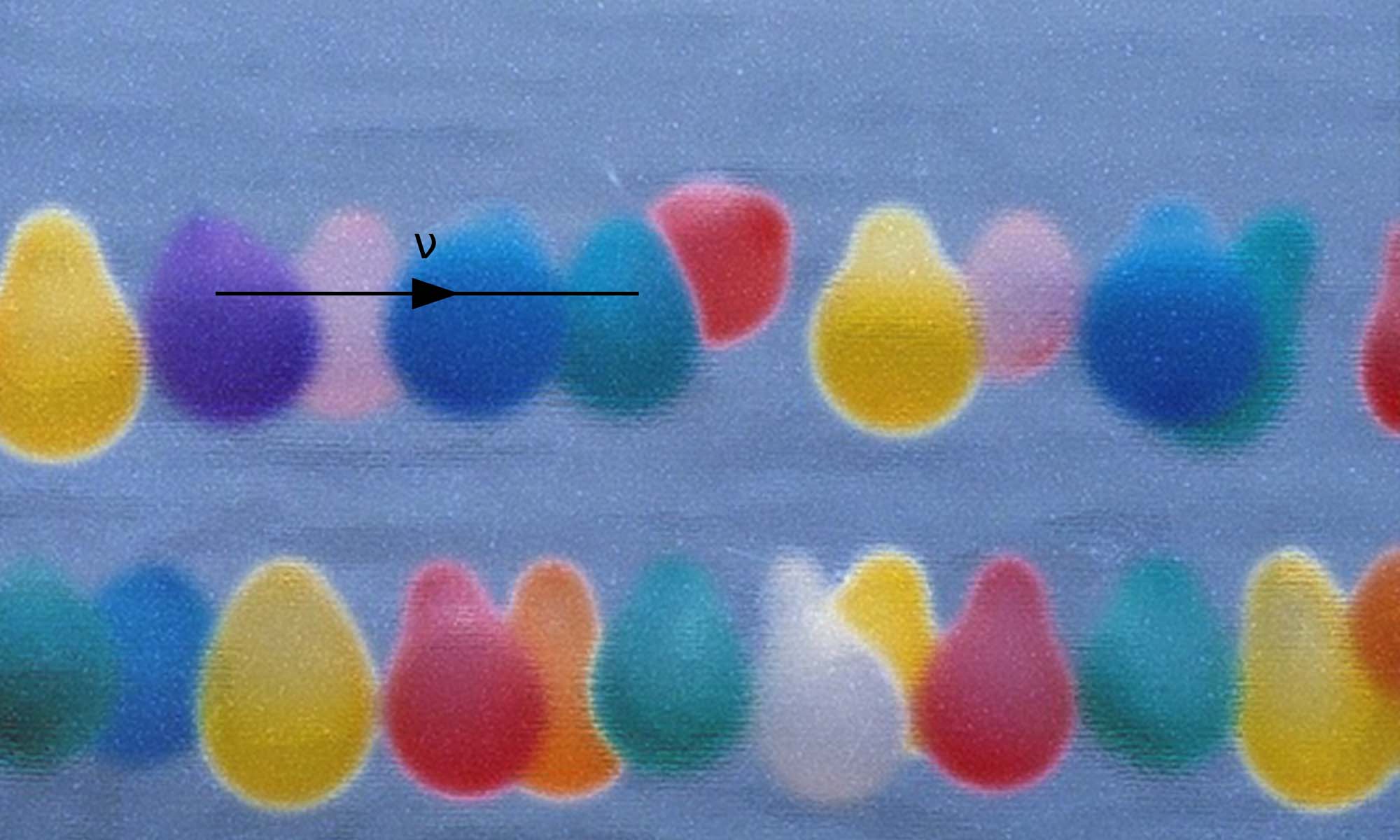

“By slamming small particles into heavy gold nuclei at nearly the speed of light, we create tiny, ultra-hot droplets of a bizarre type of matter”—his words grew louder—”called a quark-gluon plasma.” For just a few thousandths of a second after the Big Bang, the universe was so hot and dense that atoms could not form at all! Instead, space was filled with this quark soup.”

While he rambled, I considered this Paulo. He was annoying but—second life or not—he also occupied a stable and appraisable position in the life of his family. Who was I to disturb this universe? And yet I had.

“My experiments involve shooting the gold with a helium-3 atom, which produces in the resulting droplets a remarkable triangle pattern. This occurs outside of anything we might understand to be space-time in the relativistic sense…”

I watched Tommaso from the corner of my eye. His expression had darkened. He was turning inward. His blue eyes twitched and shuddered in the glare of the sun. Perspiration beaded his brow. Initially restless, then impatient, several times, he skated away from us, then returned. “Papa, I’m exploring,” he said. “Come with me. We’ll find snorkel clams.” And then these words. “They’re on the other side. Where the water’s warm.”

Paulo ignored him.

“You’re boring, Papa,” Tommaso said finally. “I am going to find, Mama. Okay?”

“That’s good, Tommo,” Paulo said. “Bring Mama back. We’ll all play together.”

Tommaso skated past me and once more, I thought I heard him, under his breath. “Go away, Teacher. Stay away. You’re ugly. You scare me.”

They retrieved his body from the canal late that afternoon. The ice had collapsed beneath him near a pumphouse, where water temperatures were typically higher and any ice that formed was rotten.

Someone later reported having seen him in the morning, seated on the bank of the canal, pulling out his toys from his backpack, moving his boat back and forth on the ice. They saw him stuff the toys back into his pack, scramble his arms through the straps, then skid from the bank to the ice and begin to skate north.

As for me, I’d watched him retreat from his father, and from me, skating lazily on the margins of the pandemonium at the center of the lake. The sun was still climbing in the east, its bright clear light refracting through the hoar-frosted trees, curtaining the shoreline like a stage set. After perhaps 200 yards, he paused near a clearing on the bank, the sun here wreathing him in cold light.

I squinted, blinked, and when I could see clearly again, he was gone. I assumed he’d hurled himself into a nearby scrum of children, perhaps having seen within it his mother. In reality, he’d simply exited the stage, his swift passage through the trees, like a scimitar, instantly slicing him from this light, and from us. ▩