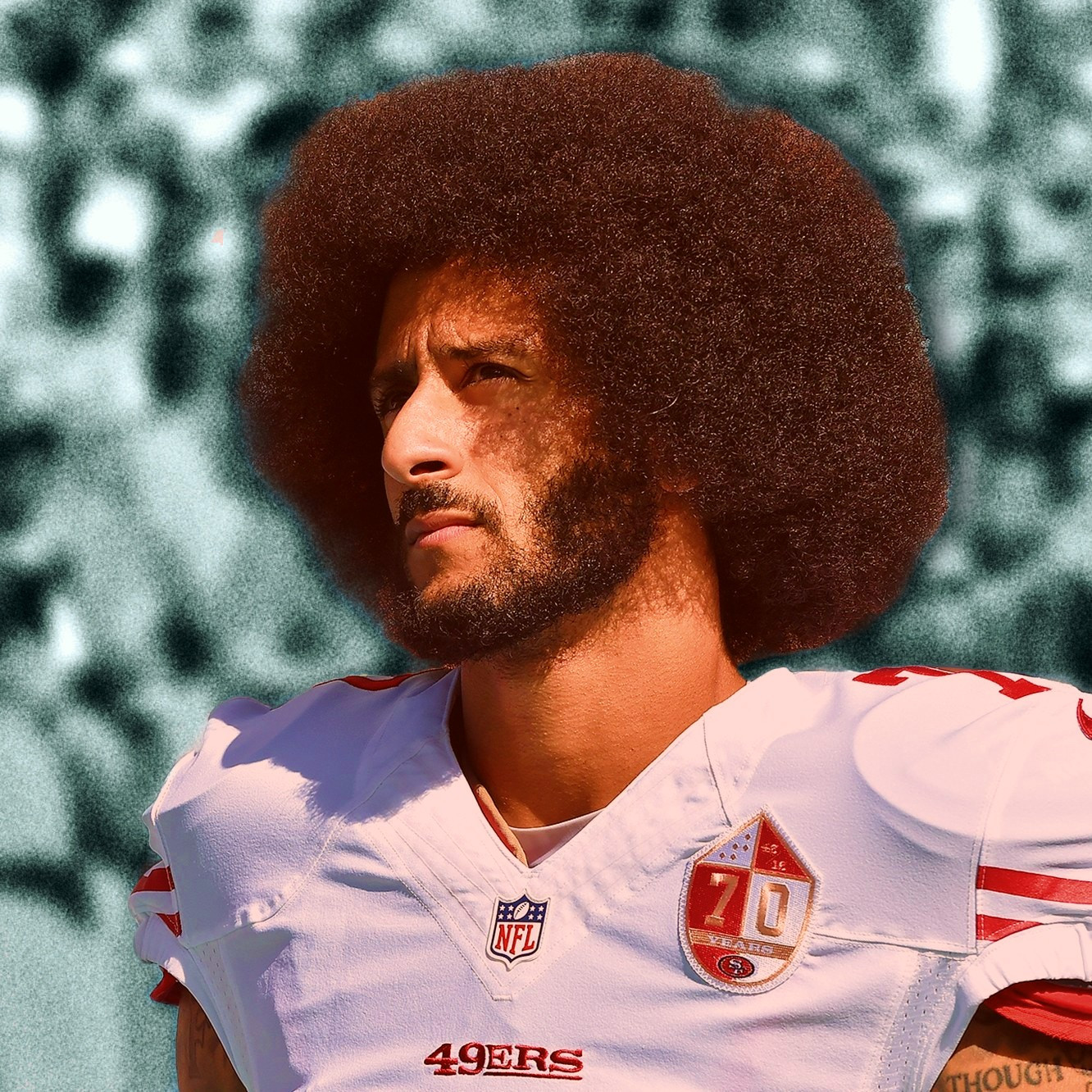

Colin Kaepernick, whose modest but courageous act of protest cast a provocative new light on nationalism and racism in the United States, is the Mangoprism Person of the Decade™ spanning from 2010 to 2019.

Through his NFL career, Kaepernick attained outsized privileges with which few in the United States could identify. His decision to kneel during the national anthem to protest police brutality, which ultimately got him blackballed from the league, is hardly one many of us are in a position to explicitly replicate. But the form his story took, of a person who happened to face down his particularly high-profile context with self-assured thoughtfulness, in effect sacrificing the relative privileges of his situation for a more interesting and meaningful existence beyond it, serves as a lesson that anyone can absorb and apply in concrete ways.

Drafted by the San Francisco 49ers in 2011 after a productive college football career at the University of Nevada, Kaepernick started his first NFL game in 2012. With a long stride and an improvisational playing style, he found immediate success, leading the 49ers to the Super Bowl and breaking Michael Vick’s playoff rushing record along the way. His 2013 season ended in a loss to the Seattle Seahawks in a dramatic NFC Championship Game. The game constituted a matchup of two dynamic black quarterbacks whose self-representations vis a vis Instagram were juxtaposed in a Seahawk’s fan’s viral post, which portrayed Russell Wilson amidst dogs, military personnel, and charitable events, and Kaepernick hanging with J. Cole and showcasing his impressive shoe collection. This post epitomized Kaepernick’s racialized media framing in the national consciousness. After a loss to the Seahawks, Kaepernick signed a $126 million contract extension with the Niners.

Kaepernick’s performance dipped somewhat in 2014 and 2015, but he remained the 49ers starting quarterback going into the 2016 preseason, when a reporter noticed him sitting down on the bench during a pregame rendition of the Star-Spangled Banner. Mainstream national discourse regarding a spate of well-publicized police killings of unarmed black men had been influenced in part by the Black Lives Matter movement, and after the game Kaepernick told reporters: “I am not going to stand up to show pride in a flag for a country that oppresses black people and people of color. To me, this is bigger than football and it would be selfish on my part to look the other way. There are bodies in the street and people getting paid leave and getting away with murder.”

In order to render a more precise message amid bad faith interpretations regarding his lack of patriotism, he knelt for the anthem during a subsequent game, in part as a show of respect to U.S. military members, and he knelt during the anthem for the entire rest of the season, inspiring similar acts among other athletes in professional and amateur contexts across the nation. The protests came amid the rising pitch of the 2016 presidential contest, in which Donald Trump effectively used the kneeling movement as a cudgel to highlight the supposed excesses of a political opposition that did not respect America’s greatness. Kaepernick, beset by injuries, missed numerous games that season, while continuing to kneel prior to each of them. In 12 games, he passed for 16 touchdowns and four interceptions and occasionally demonstrated some of the flair that propelled him to the national stage in the first place. In March of 2017, facing a release from the 49ers, Kaepernick opted out of his contract.

In the time since, in a league where the likes of Nathan Peterman, DeShone Kizer, Blaine Gabbert, Mark Sanchez, David Blough, Geno Smith, and Devlin “Duck” Hodges have started games at quarterback in the last three seasons, no team has signed Colin Kaepernick. In October 2017, Kaepernick filed a grievance with the NFL – since settled – for colluding to keep him out of the league. That same month, at an owners meeting about how best to deal with plummeting favorability ratings and boycott threats from fans who were offended by players kneeling during the anthem, Houston Texans owner Bob McNair, a major financial backer of President Trump, said of the players in a majority-black league run by a nearly entirely white ownership class: “We can’t have the inmates running the prison.” This comment prompted much of his own team to kneel during the following game in Seattle, at which, according to a Mangoprism correspondent present at CenturyLink Field, some Seahawks fans could be found casting their hands to the air in disbelief as they screamed at kneeling Texans players to “grow up!”

One thing about this whole story – and decade – is that it could be challenging to parse the substance from the noise. Kaepernick made it clear that police brutality in the United States was the subject of his protest, but media perpetuated the asinine and incoherent narrative that Kaepernick and his comrades were protesting the anthem itself and all the things it represents. (FWIW, the MP editorial board agrees with Vince Staples’ assessment that the Star-Spangled Banner “don’t even slap.”) The internet in particular has supercharged the blunt meanings of certain performative shorthand identity markers by which a person can assert their tribal affiliation in the culture wars. Sometimes, the markers became so potent that we had no choice but to choose a side. As the anthem began, anxiety swept through stadiums at the start of every game the nation round and, whether on the field or in the stands, the very fact of one’s action – or inaction – all of the sudden became meaningful in itself (with a few notable exceptions, white players opted not to protest during the anthem). An invisible political ritual previously only explicitly considered on the fringes of mainstream discourse became entirely conspicuous to pretty much everyone. Does this matter?

As Ameer Loggins, who shared political reading materials with and had a class on black media representation audited by Kaepernick at UC Berkeley during the summer of 2016 told the journalist Rembert Browne, “Colin represents an inconvenience.” The NFL’s brand – violence, military partnerships, the lucrative Viagra marketing contracts that adorn its every game, its evident comfort at the center of American nationalism and consumer culture – proved shockingly fragile in the face of this gentle disruption of its harmoniously choreographed antiseptic image. Notably, the people who were triggered by this disruption stood not on the supposedly reactionary political left, but among the true believers, the diehards who have staked so much of their identity – or in the case of owners and ad partners, finances – in the NFL’s inane theatrics.

That a mere “inconvenience” could so shake such a powerful institution is a testament to the power of rhetoric and action that does not conform to the banal political platitude perpetuated in the interests of that institution. As the writer George Orwell wrote in his classic “Politics and the English Language,” political, as opposed to meaningful speech like Kaepernick’s, “give[s] an appearance of solidity to pure wind.” Enjoining us to deal in authentic and thoughtful discourse generated from our own personal convictions and feelings, Orwell added, “probably, it is better to put off using words as long as possible and get one’s meaning as clear as one can through pictures and sensations.”

Kaepernick, whose fabulous afro no doubt in itself rankled some of the more unsubtly racist owners in the National Football League, cut a powerful image on the sidelines that demonstrated his dissent from one of the most idiotic and thoughtless mainstream institutions in American cultural life. Kaepernick chose a meaningful life on his own terms and solidarity with those who have less power than himself, over mere status contingent on the edicts and regulations of the cynical power-hungry men who own the NFL and, more broadly, so much of American society.

For the inconvenient example he set, the Mangoprism editorial board is delighted to award Colin Kaepernick our highest honor: the Mangoprism Person of the Decade™. ▩

Runners up: Beyoncé, Marshawn Lynch