When Danny asked me to write about Nate Dogg, the gears in my brain immediately started spinning. It’ll be easy, I thought, to write a tribute to my most beloved musician. If only.

I thought about reactions different people had when I told them my favorite artist was Nate Dogg. West Coast folks usually at least knew who he was, but the average respondent couldn’t name one of his songs beyond “Regulate.” East Coasters asked, “You mean Snoop Dogg?” forcing me to perform incredible feats of self-restraint in not pimp-slapping them on the spot for being ignorant.

Nate Dogg is perhaps most widely recognized for being on the forefront of the G-Funk movement. Actually, the above paragraph shows I know jack shit about the broad perception of Nate Dogg. In any case, helping create G-Funk is how Nate Dogg really came up in the game.

The public’s first exposure to Nate was ever so appropriately via “Deeez Nuuuts” off Dr. Dre’s The Chronic in 1992. After Dre, Snoop, and Daz Dillinger (then known as “Dat Nigga Daz”) finish rapping, Nate comes in on the outro, sings “Aaaaaaaye can’t be faaaaded, I’m a nigga from the mothafuckin… streets” four times, then shows off his incredible vocal range for eight bars, all the while repping Dre and Death Row to the fullest. The very next song on the album features Nate on the hook, showing off a vibrato that can only be described as ghetto-opera in style. All of the sudden, Nate Dogg was prominent in the public eye.

Soon after, in perhaps his most famous appearance, Nate costarred with Warren G in the hit “Regulate.” Costarred might be the wrong word. Nate stole the show. Let’s examine the story arc of the song. Warren G is whippin’ through Long Beach trying to find some female companionship for the evening. He soon gets distracted by a dice game and decides he wants to join. He “jumps out the ride and says what’s up” before the people in the game pull guns on him, taking his rings, Rolex, and dignity. Warren G is, essentially, Ashy Larry from Chappelle’s Show.

Luckily for Warren G, Nate Dogg is on the scene. He’s looking for Warren, fending off lady-folk who try to approach him, because he keeps his eyes on the prize. Unlike Warren G. Nate realizes he’d “best pull out his strap and lay them bustas down,” scattering Warren’s attackers, saving his bitch ass, and in the process, Regulatin’.

The rest of the story is rather simple. Nate retraces his steps to the girls he previously ignored, picks them up, and provides a couple to Warren G before they hit the next stop, the Eastside Motel. After a chorus break, Nate proclaims his and G-funk’s place on top of the rap game.

G-Funk was a subgenre that fit Nate perfectly, and he knew that. During its brief (roughly 1992-1995) era of dominating West Coast hip-hop, Nate experienced what was essentially his only period of superstardom. Mainstream eventually left G-Funk behind, Nate never departed from it.

G-Funk, “Gangsta Funk,” allowed Nate Dogg to combine the formative elements and locales of his upbringing. His voice was developed in the gospel choirs of Mississippi, while his personality and worldview were shaped by running the streets of Long Beach with his cousin Snoop Dogg during his teenage years. G-Funk allowed the synthesis of his distinctive musical sound and gangsta lifestyle.

His first album, G-Funk Classics, Vol. 1 & 2, was released in 1998, long after G-Funk had fallen from its perch atop hip-hop. His second album, 2001’s Music and Me, saw slightly better sales, but did not re-vault Nate into the upper echelon of rap.

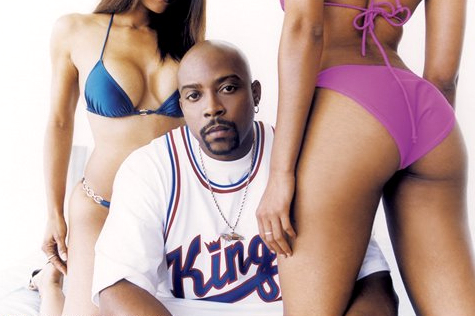

Hip-hop is distinctly regional – the first label every artist receives is their coast, city, or hometown. Rappers then seek to rep that label, spreading the predetermined message of their locale. At first glance, Nate Dogg’s message seems to be a simple one: “Disregard females, acquire currency” – that of a pimp. The album cover of Music and Me agrees with this interpretation.

Woven into the majority of lyrics on his own songs are tales of him tooting it and booting it when YG was still a toddler. But on occasion, Nate reveals more to himself that just that, an unexpected depth of character explaining his ability to make a commitment to a single woman. On “Scared of Love,” he croons, “When they asked me why I don’t like love / Or why I don’t have a lady / Maybe it’s because I know / As soon as I tell her how I feel about her / As soon as I act like I love her, she’s gone”

While the expression of interest by the female is often the reason Nate ceases contact with that individual, he has undergone the same experience himself. We see a similar instance on “Never Leave Me Alone,” Nate telling us, “They tell me that temptation / Ooh, is very hard to resist / You tell me that you want me / I tried to hide my feelings, D-O-G’s ain’t supposed to feel like this”

The true Nate Dogg is hard to identify. Is he a real P-I-M-P, as he proclaims on the aptly named song? Is he scared that he will never find that special someone? The idea begins to emerge that Nate doesn’t even truly know who he is, perhaps unable to reconcile the pull of Mississippi religion with Long Beach pimpin’. With time, his lyrics eliminate this tension. He drifts away from sensitivity and into misogyny. Abandoning the intricacies and difficulties of relationships and attachment, Nate instead settles in to the role of using women. He distances himself from any potential emotional distress by establishing a disconnect between his body and mind, essentially leaving his mind behind. Why worry about love when you can take on the persona of a pimp?

Nate Dogg was unable to find commercial success in his attempts to preach the lifestyle of Long Beach and the gospel sound of Mississippi. In order to reach a broader audience, Nate adopted an alternative strategy – singing the hooks on other rappers’ singles, branding himself as a key ingredient in making a top song. Again, with only eight to sixteen bars to establish his message, nothing as emotionally complex as his early work can be eluted from his verses.

Unfortunately, Nate was taken from this world too soon. From late 2008 to his death in 2011, he was confined to bed after a series of strokes. He was essentially unable to speak during this time, his incredible voice never to return. It wasn’t until about 2006 that I truly became a Nate Dogg fanatic, along with a friend of mine. Upon reading about how his mother was reading fan letters aloud to Nate while he attempted recovery, we vowed to write him. We never did.

How can I, how can any middle-class white kid relate to hip-hop the way we do? Why did Nate Dogg’s music touch me in such a profound way? Why does it continue to do so? Every teenager and young adult is scrapping through life, dealing with pain, pleasure, acceptance, and rejection, trying to find out who they really are. We see Nate Dogg take on this same experience, and, rather than fighting it, taking the flight response we all so desperately want to fall back upon. Why cope with the hardships of searching for love and companionship when Nate Dogg can forget all about it, sing, engage in only physical relationships, pimp, and hey-ey-ey-ey-ey, smoke weed every day?

Does Nate Dogg take the easy way out by doing this? I don’t think so. He simply takes the Epicurean view of the world, seeing pleasure as the absence of pain. Did he follow this philosophy in life? Not so much. It appears that he was a pretty jealous guy. Adopting his musical persona, Nate Dogg realized that he could distance himself from everything that could potentially harm his soul, so he did. His greater purpose in life was to bring happiness to those who listened to his music, realizing that choruses on others’ hits were the perfect medium to accomplish that. He escaped from his problems by singing. Along the way, he happened to unearth one of the great philosophical truths of the past two decades: Pimpin’ can, in fact, be easy.