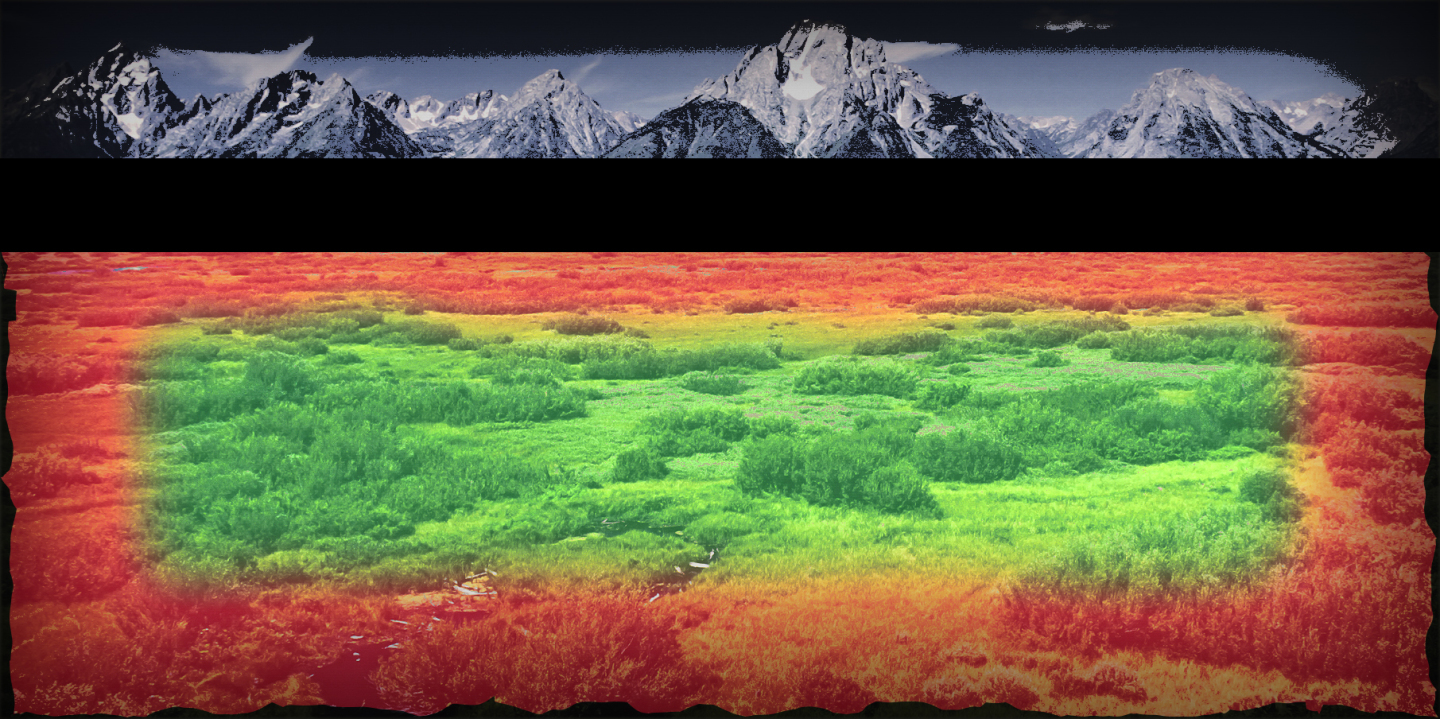

Driving west Wyoming Highway 26 Bridger-Teton National Forest. Grey trees line the road, brown evergreens slouch for miles. The mountain pine beetle makes sounds imperceptible to the human ear as it bores into the venous water systems of high-elevation pines. Are these sounds music? If so, is this what climate disruption sounds like?

In this place, outside Grand Teton National Park, the effects of human-caused climate disruption are salient, amplified and felt. You can smell the smoke of wildfire carried north from Colorado, see the browning hillsides, feel the dead bark of trees and hear the mountain pine beetle. In this place, I am at the same time enthralled and grieving as I become hyper-aware of the dying beauty around me. This moment is what I left Chicago for and makes me aware of the disconnection from the earth I have been feeling the last five years. In the silence of the woods, I feel for the first time in a while that I can hear.

Cities have turned down the volume of the surrounding environment and tuned our ears to purely human channels. On these channels and networks, ecological-awareness transmits as read or watched information sometimes invoking emotional reactions, but always at least one step removed from the experience itself. But even in the city, even in your room, environment and ecology persist. Always being drawn to sound and music, I used to record walks in the city and my room to experience my environment in a more first-hand way. Listening back to these recordings, I question whether the city turns down the environment or if humans selectively tune out everything beyond ourselves. The microphone is a beautiful equalizer, and I now hear the rain, and the evening frogs in the park next door, the birds in the morning and the wind. Suddenly it’s difficult to make out what the person beside me is saying in the clatter of the coffee shop as steam shoots from metal tubes and a dog barks outside.

While we may not be depending on our environment on a day to day basis as humans once did, the continued existence of humans on this planet depends a great deal on tuning our awareness toward the earth – our lives depend on it. I propose this tuning can start with changing our listening in a conscious and directed way. In changing our listening, we can, as Donna Haraway phrases, “stay with the trouble” day to day and orient our decisions and actions around embodied experience rather than abstract fact.

Of all the ways we listen, music presents the most fluid arena for changing and tuning listening itself. However, not all music draws the environmental to the listener: most musics and their mediums of listening have the exact opposite effect, of drowning out the environment and presenting a sterilized recorded music to match. Environmental music, on the other hand, contains a capacity beyond itself and opens the ears to a wider breadth of listening and being in the world. To an extent, the lines I draw in this distinction have to do with conventional and experimental music. The former is entrenched within itself and limited by a conventional understanding of music as a particular kind of organized sound containing what we understand in the West as harmony, melody and rhythm. This is not to say that conventional music can’t challenge a listener, but rarely, if ever, does that challenge aim beyond established forms and structures within conventional music. Experimental music, on the other hand, contains a greater capacity to challenge larger concepts in music, and music itself. This last point is critical to moving toward an environmental music, and explains why the experience of experimental music – both creating and listening to it – is essential to developing a listening practice able to draw us closer to our environment.

Music, what does it communicate?

John Cage, Silence, “Composition As Process – III. Communication” pp. 41

Is what’s clear to me clear to you?

Is music just sounds?

Then what does it communicate?

Is a truck passing by music?

If I can see it, do I have to hear it too?

If I don’t hear it, does it still communicate?

Which is more musical, a truck passing by a factory or a truck passing by a music school?

Are the people inside the school musical and the ones outside unmusical?

What if the ones inside can’t hear very well, would that change my question?

Do you know what I mean when I say inside the school?

Are sounds just sounds or are they Beethoven?

People aren’t sounds are they?”

Maverick Concert Hall, Woodstock, New York, 1952. Pianist David Tudor walks across the stage, sits down, opens the score in front of him, opens the keyboard lid, starts a timer, and, then, does nothing. Three turned pages and four minutes and thirty-three seconds later, he closes the piano, stands, gives a nod and walks of the stage. This piece, 4’33”, left a deep mark on contemporary classical music and its influence on experimental music continues through today. Connected to his writing above in the collection of essays, Silence, much of John Cage’s music questions music itself and the conceptual potential it contains when stretched to its limits. As related to a conception of environmental music, 4’33’’ questions “silence” by allowing the room — the people creaking in their chairs, the traffic outside etc. — to inhabit the space music generally occupies in a concert hall. In doing this, Cage elevates those sounds to the importance of music and creates a potential for a listening awareness tuned better to the environment.

In David Toop’s excellent exploration of the history of ambient music, Ocean Of Sound, Brian Eno describes a similar musical exercise: “I had taken a DAT recorder to Hyde Park and near Bayswater Road I recorded a period of whatever sound was there: cars going by, dogs, people. I thought nothing much of it and I was sitting at home listening to it on my player. Suddenly I had this idea. What about if I take a section of this – a 3½ minute section, the length of a single – and I tried to learn it? … I tried to learn it as one would learn a piece of music: oh yeah, that car, accelerates the engine, the revs in the engine goes up and then that dog barks, and then you hear that pigeon off to the side there.” In this exercise, Eno peels back a notion that only human composed sounds can be musical observing that with sufficient listening and music-making on the part of the listener any arrangement of sounds can become musical. In doing this exercise we can all become composers and music makers of the world around us and in doing so become more aware and compassionate of the dying ecosystems we inhabit.

Outside of his musical philosophies, Brian Eno’s music provides its own experimental, environmental bent. The classic Ambient 1: Music For Airports is especially relevant to this discussion because of the environmental specificity of the composition. In his own words, Eno hoped to “produce original pieces ostensibly (but not exclusively) for particular times and situations with a view to building up a small but versatile catalogue of environmental music suited to a wide variety of moods and atmospheres.” (Liner Notes 1978) Attached to Eno’s conception of an environmental music for non-musical spaces is also the radical idea of creating music intended to be heard but not listened to. Eno believed that the greatest ambient music would supplement the environment without completely covering it – a music in ecological harmony. In using and making ambient music we can move to a musical and listening space that includes the environment.

I think that that which is called ear training in music schools is really wrong. You can’t train the ear it does what it does. But what can be changed is listening.

Pauline Oliveros

Lastly, Pauline Oliveros’s Deep Listening work is important for developing more environmentally inclusive listening practices and compositions accessible to anyone. From the introduction to her 1974 book of compositions, Sonic Meditations: “She attempts to erase the subject/object or performer/audience relationship by returning to ancient forms which preclude spectators. She is interested in communication among all forms of life, through Sonic Energy. She is especially interested in the healing power of Sonic Energy and its transmission within groups.”

In trying to achieve these goals, Oliveros’s compositions and music-making projects center on procedures that incorporate the following four elements:

- Actually making sounds

- Actively imagining sounds

- Listening to present sounds

- Remembering sounds”

The realization of these concepts result in compositions like “Native”:

“Take a walk at night. Walk so silently that the bottoms of your feet become ears.”

You will notice that all of Oliveros’s Sonic Meditations work is textual without any traditional music notation; this allows anyone who can read to perform the composition. Taking this equalizing maneuver between “musicians” and “non-musicians” a step further, Oliveros’s emphasis on listening itself as a mode of music-making brings non-human performers into the music-making process further shattering the humanistic hierarchy between music, noise and sound. Like much of what I am presenting as environmental music, Deep Listening music is a momentary and embodied practice which cannot be captured on tape. 4’33” and Music For Airports, while “recordings” exist also exist in an uncomfortable relationship with recorded music in both the conceptual and space-focused territory they represent.

Over the past 100 years, recorded music has largely subsumed our collective idea of what music is and can be. Even live music, in a conventional context, aims primarily to duplicate previously recorded sounds. While I don’t believe the past 100 years of recorded music should be tossed out, I do think recorded music and environmental awareness currently stand in opposition. By opening our musical conception to contain music that questions and seeks to broaden our listening, we can build and maintain a deeper connection to our environment. The three artists introduced above provide a jumping off point toward a world of music that, met with an open mind, holds the potential to expand what music can be. While these actions and explorations will not in themselves solve the current crises at hand, they are a way to begin reorienting our priorities and awareness outside of ourselves and toward the disappearing ecologies we are a part of. Perhaps, listening deeply, we can hear the mountain pine beetle and know that we are implicated in its rising sound. ▩