The Winter of Despair: Jan Palach and the Collapse of the Prague Spring | Kurt Treptow | The Ukrainian Quarterly, 1990

The Prague Spring and Its Aftermath | Kieran Williams | Cambridge University Press, 1997

Struggle and Martyrdom in Islam | ed. Mehdi Abedi and Gary Legenhausen | Institute for Research and Islamic Studies, 1986

In January 1969, in Prague’s Wenceslas Square, a 20-year old college student named Jan Palach set himself on fire. Today, Palach is immortalized across the city in statues and plaques for his act of political protest, which would inspire Czechoslovakians for decades and eventually helped animate the Velvet Revolution.

In January 2018, minutes after leaving my first orientation for a study abroad program, I stumbled across some of these memorials: two statues and an accompanying poem. I had arrived at Václav Havel Airport the day before, with a massive suitcase and one hefty winter coat. A large group of other American students loitered and talked by the baggage claim. Group by group, we were sent into the city by program employees, who translated our addresses for the taxi drivers. I arrived at my program-rented apartment and met the three other American girls who’d be my roommates. That evening, we went for dinner with the downstairs apartment—also program students. By the next day, after an orientation in a Charles University building—with its view through double-paned windows across the Vltava River—I was socially spent.

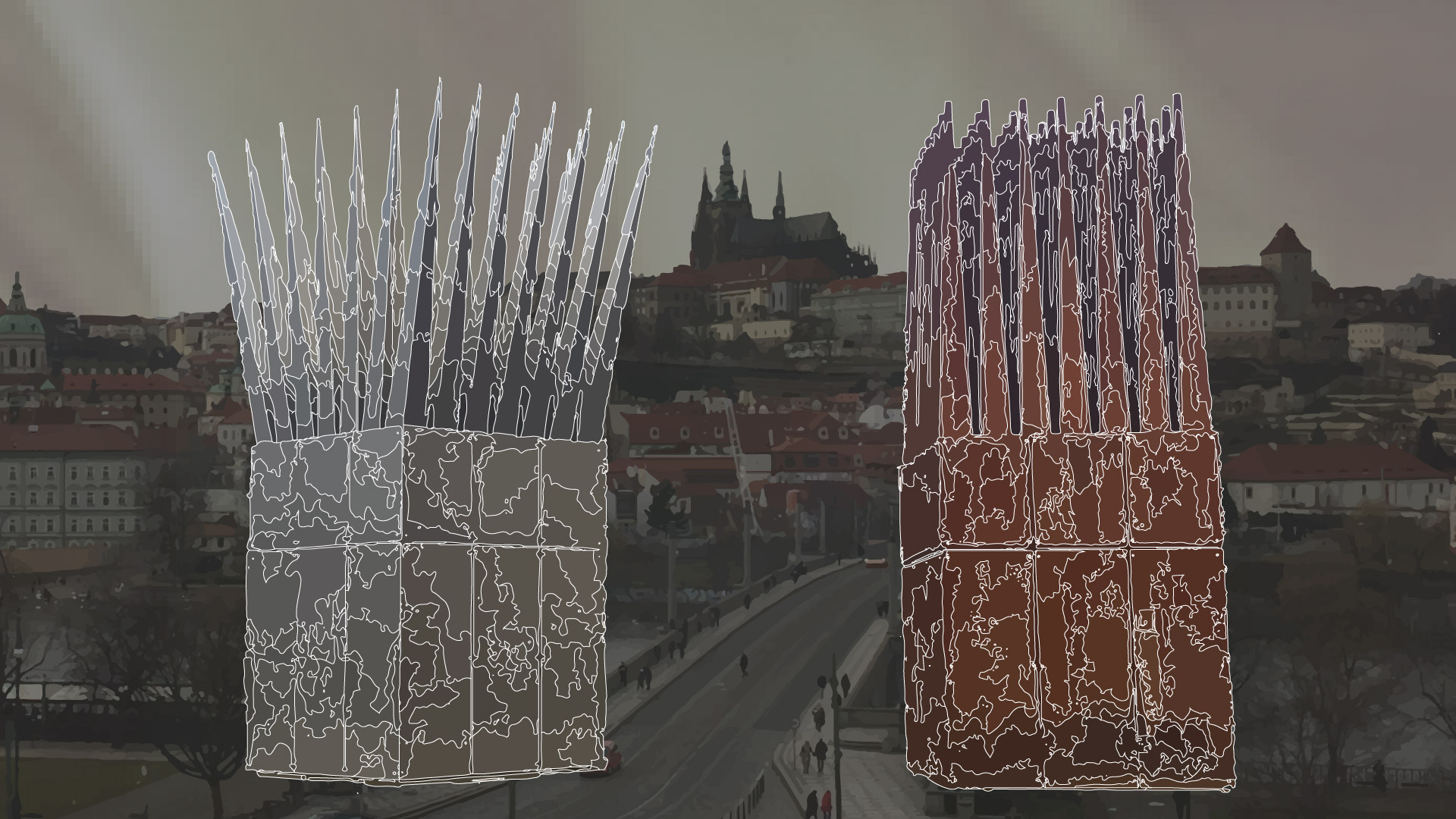

I gratefully moseyed in silence towards the river. Three months in Prague! Foreign city, foreign language, hordes of new, unknown American students to sift through in search of friends … and there they were: two tall metal statues planted by the river, one a smooth, shiny silver, the other a dark, rusted brown. Each had a cubic base, with long, regularly-spaced spikes emerging from the cube’s top face. The silver statue’s sharp, pointy spikes angled away from each other. The rusted brown statue’s dulled spikes rose straight up. Beside them, a poem:

The Funeral of Jan Palach

When I entered the first meditation

I escaped the gravity of the object,

I experienced the emptiness

And I have been dead a long time.

When I had a voice you could call a voice

My mother wept to me:

My son, my beloved son

I never thought this possible,

I’ll follow you on foot.

Halfway in mud and slush the microphones picked up.

It was raining on the houses

It was snowing on the police cars.

The astronauts were weeping

Going neither up nor out.

And my own mother was brave enough she looked

And it was alright I was dead.

This was the first I had ever heard of Jan Palach. The strange, blunt features of the statues against Prague’s gray winter sky intrigued me, as did the poem’s haunting, mournful atmosphere.

Last month, Aaron Bushnell, a 25-year-old active duty member of the U.S. Air Force, posted on Facebook: “Many of us like to ask ourselves, ‘What would I do if I was alive during slavery? Or the Jim Crow South? Or apartheid? What would I do if my country was committing genocide?’ The answer is, you’re doing it. Right now.”

Then he lit himself on fire in front of the Israeli embassy in Washington, D.C. “I will no longer be complicit in genocide,” he said in a video of the self-immolation. “I’m about to engage in an extreme act of protest, but, compared to what people have been experiencing in Palestine at the hands of their colonizers, it’s not extreme at all. This is what our ruling class has decided will be normal.”

Hearing about this, I immediately thought of Palach. Would Bushnell’s act prompt wide-scale political action? Would it simmer in the national consciousness only to erupt years later? Or would it disappear, forever a blip in a news cycle? What was it that gave Palach’s specific act such enduring political significance?

I had investigated this question before, while researching Palach in the fall of 2018, after returning to my usual college life in Washington state. I’d found that most English-language texts addressing him did so only briefly. Yet the process by which a human life can end and take on a political life has been examined, by thinkers across the world. The 20th century Iranian intellectual Ali Shariati, for one, analyzed the “shahids” who he said played a prominent role in the Iranian Revolution—yet his insights have rarely been applied to other political contexts.

Palach’s immolation came during a period of dashed optimism, after the so-called Prague Spring. It was only the year before that Alexander Dubček, the head of the Czechoslovakian government, pushed for liberalizing reforms that were intended to give socialism a “human face,” a now-famous phrase. While these reforms were popular among everyday Czechoslovakians, the Soviet Union and other members of the Warsaw Pact feared a threat to communism’s future in Czechoslovakia and beyond. In the evening of August 20th, 1968, Soviet forces invaded and occupied the country to halt the reforms’ implementation.

At first, Soviet suppression of the Prague Spring was met by a rise in Czechoslovakian political activity and protest. Student groups, the working class, and the intelligentsia presented a strong oppositional front, but they either “stopped short of making a real challenge” or grew demoralized by a lack of progress. The Soviets moved to reestablish a sense of normalcy and discourage political protest. “By January, 1969,” wrote the historian Kurt Treptow, “despondency and apathy were becoming widespread.”

It was in response to this growing resignation that on January 16, 1969, Palach walked to Prague’s Wenceslas Square and set himself ablaze. Notably, Palach’s immolation didn’t explicitly protest the invasion itself; it was targeted at the Czechoslovakians—aiming to jolt them out of their political apathy. Three days later he died in the hospital from third-degree burns.

Shariati, an intellectual figurehead in the Iranian Revolution of 1979, examined the shahid: an individual who chooses to sacrifice their life for a larger cause. In purposefully sacrificing themselves for an ideal, the shahid absorbs the cause’s value into themselves. By doing so, in their death, they leave behind the realm of mere personhood and become “thought itself”; the shahid becomes the very ideal they died for. Importantly, the shahid dies for an ideal that is fading away, resurrecting it with their death. The shahid “calls it back again to the scene of the world. By sacrificing his existence, he affirms the [hitherto] vanishing existence of that ideal.” Here lies the shahid’s particular power. The shahid outlives their own death by embodying the ideal whose existence they renewed in the act of dying; the shahid remains present even after death.

Shariati used the “blood and the message” to describe the respective tasks of the shahid and their survivors. The “blood” refers to the shahid’s death. The “message” refers to the responsibility to spread the shahid’s message, which weighs on the survivors. These survivors, he argued, are obliged to align reality with the principles for which the shahid sacrificed themselves—creating new communities and societies that exemplify those ideals.

Like Shariati’s shahids, Palach actively chose his death. He also fulfilled the shahid’s essential role of “witness,” in his effort to renew life to the cause of Czechoslovakian autonomy. In his suicide note, Palach wrote, “Because our nations are on the brink of despair, we have decided to express our protest and wake up the people of this land. … Remember August. In international politics a place was made for Czechoslovakia. Let us use it.” (Palach initially claimed to be part of a group whose members all intended to immolate themselves in political protest, hence the use of “we”; it is still unclear if there ever was such a group.)

In an echo of Shariati’s “blood” and “message” distinction, Palach distinguished his act from the actions he hoped to prompt among the Czechoslovakian people. He describes his task: to die, to jolt the people of Czechoslovakia out of their political apathy by killing himself, and the task of the Czechoslovakians: To spread Palach’s message, and fight for freedom from the Soviets. Palach’s comments on his deathbed highlight this distinction: “My act has achieved its purpose. But it would be better if nobody repeats it. Lives should be used for other purposes.”

Shariati argued that “if blood does not have a message, it remains mute in history.” Palach’s suicide inspired a number of immolations by other Czechoslovakians, but none had a comparable impact. In the month after Palach’s death, Jan Zajic, for example, lit himself on fire and also left a suicide note. But this letter “differs significantly from Palach’s,” Treptow wrote. “It does not outline a specific political program … Zajic’s suicide was a protest of despair … rather than an act to achieve a positive political result.”

Zajic’s suicide left behind no “message” in the sense Shariati describes — and according to Treptow it “aroused little public anxiety.” Palach, in contrast, articulated a specific political message, and thus left behind a specific political duty to be fulfilled. As long as the Czechoslovakians remembered Palach and spread his message, he remained a potent symbol, a rhetorical embodiment of the cause of Czechoslovakian self-determination that could be used to serve that very end.

The days immediately following Palach’s death saw increased political activity. On January 24th, 1969, a minutes-long national strike paid tribute to Palach, and his funeral the next day was attended by hundreds of thousands of Czechoslovakians.

Yet these collective actions failed to coalesce into an immediate political force. While Dubček may have supported the sentiments driving Palach’s self-immolation, he was not, Treptow wrote, in a position to make any concrete policy changes. And as Czechoslovakian politicians struggled to find a balance between honoring Palach’s act and discouraging copycats, Czechoslovakians, particularly students, began to feel disconnected from the country’s leadership, identifying them more with the Soviets rather than the Czechoslovakian populace. This allowed the Soviet Union to remove reformist politicians without fearing the public backlash that had been previously anticipated. Dubček’s eventual removal from office marked the definitive end of the Prague Spring and any potential for real reform, sending Czechoslovakia into a period of political despondency.

Neither anti-communist sentiment and protests nor Palach’s political force, however, ended with Dubček’s removal. Twenty years later, in 1989, the Czechoslovakian communist regime fell. While historians primarily view this collapse in relation to a period of mass protests and strikes in November of that year, its seeds were planted months earlier, in January, with a week of demonstrations commemorating the 20th anniversary of Palach’s death.

Police beat and arrested the peaceful protestors, foreshadowing dynamics to come. Notably, Václav Havel and 14 others were arrested for laying flowers at the location of Palach’s immolation, cementing Havel’s role as the leader of the anti-Soviet resistance. This week of clashes is now regarded by some to be the real beginning of the revolution that culminated in the overthrow of the communist system.

The year proceeded with sporadic protests and demonstrations, and on November 17th, a peaceful student march was met first with police and other government forces who violently forced the crowd to disperse, injuring hundreds of protesters in the process.

The next nine days were marked by mass protests with hundreds of thousands of attendees and strikes of increasing proportions. By the end of these ten days, communist leaders begrudgingly realized the only way to resolve the crisis would be to concede to the opposition’s demands. The Communist Party initially hoped to maintain political relevance by only removing certain politicians without disrupting the underlying order. Ultimately, however, this plan proved fruitless and had to be abandoned. On December 10th, a new government was formed and President Husák resigned, leaving the resistance movement, called the Civic Forum, in control.

A year later, Prague’s Red Army Square was renamed Jan Palach Square. Before thousands of attendees, Havel, who became the last president of the new Czechoslovakia and the first of Czech Republic, recalled the protests of 1989, saying, “I had a feeling then that after 20 years, the great Jan Palach’s ultimate sacrifice was beginning to take on its full meaning … Now I’m certain of it.” ▩