I was still in a bit of a stupor the morning after the Super Bowl. Actually I was completely delirious. My voice was hoarse from screaming Richard Sherman quotes at passersby after the game. A Seattle team was world champions, in the most convincing fashion imaginable, and I wasn’t quite sure what to do with myself. I drunkenly stumbled around in a snowstorm at 10:30 AM trying to decide whether I was in any state capable of going to work. I then got an email from Sunil Gulati, co-instructor of the course I TA, saying that Casey Ichniowski had suddenly passed away.

When I arrived at Columbia three years ago, sports were everything. Growing up, my dream was to become a sportswriter. My friends and I started a copyright-infringing paper called “Fox Sports World” in second grade. I had written for my high school newspaper, a local sports blog, and a national NBA scouting website. The path to becoming a sports journalist was clear, bordered by lush vegetation and the scent of fresh flowers. A dense fog obscured all other paths.

The sports path became even more enticing my freshman year when I got a job with Casey Ichniowski, a labor economist and professor at the Columbia Business School. I began working as a research assistant on two projects. The first project sought to quantify the effect a player’s March Madness performance had on where he would be picked in the NBA Draft. The second project sought to establish whether star players on relatively weak national soccer teams made their teammates better.

Of course, I was just excited to be doing research on sports. My goals at this point were shifting from journalism to the front office – to be general manager of a sports team. I tried to shift my academic interests towards advancing that end. There was just one problem – I simply did not enjoy economics classes. During my sophomore year it became readily apparent that my academic passion was earth science, not anything related to sports.

My meetings with Casey became more frequent during that year as the paper about March Madness approached completion. In early March, the paper was submitted and released to positive reviews from fellow economists, but a tepid response from those in the basketball industry. I relayed some of the negative comments from basketball writers and scouts the next time I met Casey and received a surprising response.

He told me, “It’s not just about sports.” He explained what I’d known all along, but never truly grasped about the basketball and soccer projects I’d worked on – the research was about something bigger. Sports were just a medium Casey used to answer fundamental questions about labor economics. In the basketball paper he found that executives use rational decision-making processes when evaluating employees. In the soccer paper he found that peer effects are hugely important in the workplace, that “Hiring high talent workers has spillover effects.”

Casey and I, it turns out, had blazed similar paths. Our athletic careers ended in high school, but our love for sports never waned. Our academic interests deviated from sports, but we kept them in our lives nonetheless. The past two years, Casey and I worked together to develop a sports management course for MBA students at Columbia. The first edition of the class, last spring, was a success, though an incredible amount of work. We met every week, sometimes getting distracted and talking about sports, sometimes rigorously planning our next steps to improve the course. No two meetings were the same – the only constants were his impeccably groomed mustache, thirty years in the making, and the fuss of hair that migrated from on top of his head to the front no matter how often he fixed it.

At that point, Casey and I were the only remaining members of the sports group that had once bustled with undergraduate research assistants. The course we were planning was six years in the making, but had never gotten off the ground. I like to think the class finally happened because Casey wanted to keep sports an active part of his life. His children had all entered college; his time coaching youth sports was over. The basketball and soccer projects had mostly concluded. The course was the link back to what he loved so much. It was certainly that way for me – working on my thesis in oceanography, spending almost all my time in the lab, meeting with Casey in his office was my escape back to my purest love.

The course was off to a strong start this semester. With a year of experience and improvements under our belts, the first class went swimmingly. It seemed that Casey, Professor Gulati, and I had created an exceptional class. Then Professor Gulati’s email came, Casey was gone from our lives, and my world had been jolted into disequilibrium. The week after the Super Bowl was extraordinarily difficult. I struggled to balance the exuberance of winning the Super Bowl with the sorrow of losing one of my closest mentors.

I attended Casey’s funeral the Saturday after the Super Bowl to pay my respects. Casey was always there for me – he talked me about my academic path, my career goals, and my general interests. He was the first person I talked to about my mom receiving chemotherapy, the first person to give me perspective and hope about the situation. We talked about our families a lot. I had only met his wife and one of his children briefly, but Casey made me feel like a member of his family, and I tried to make him feel like part of mine.

“It’s not just about sports” is the most important advice I have ever received in my life. It drove me to seek out a path in earth science, which provides fulfillment in a way sports never could. I could have easily followed the first path presented to me and worked for a sports team, with the highest priority making an owner more money – even winning is simply a conduit for that. But Casey helped me see that there was more to the world than that – that I could make a bigger impact somewhere else and still be just as passionate.

The course was how we both connected back to the sports world. It was a bond we shared that was forged by our mutual love for it. The course is continuing on after Casey’s death, with Casey, as Professor Gulati eloquently put it, “working remotely.”

At his funeral, I listened to speaker after speaker share their memories with Casey. Everyone in his life relished the moments they spent sharing their love of sports with him, how strong a connection they were able to develop over that one topic. I thought about how excited I’d been to talk about the Super Bowl with him, for him to share my joy in the Seahawks winning, to hear him talk about the greatest sports teams of his lifetime.

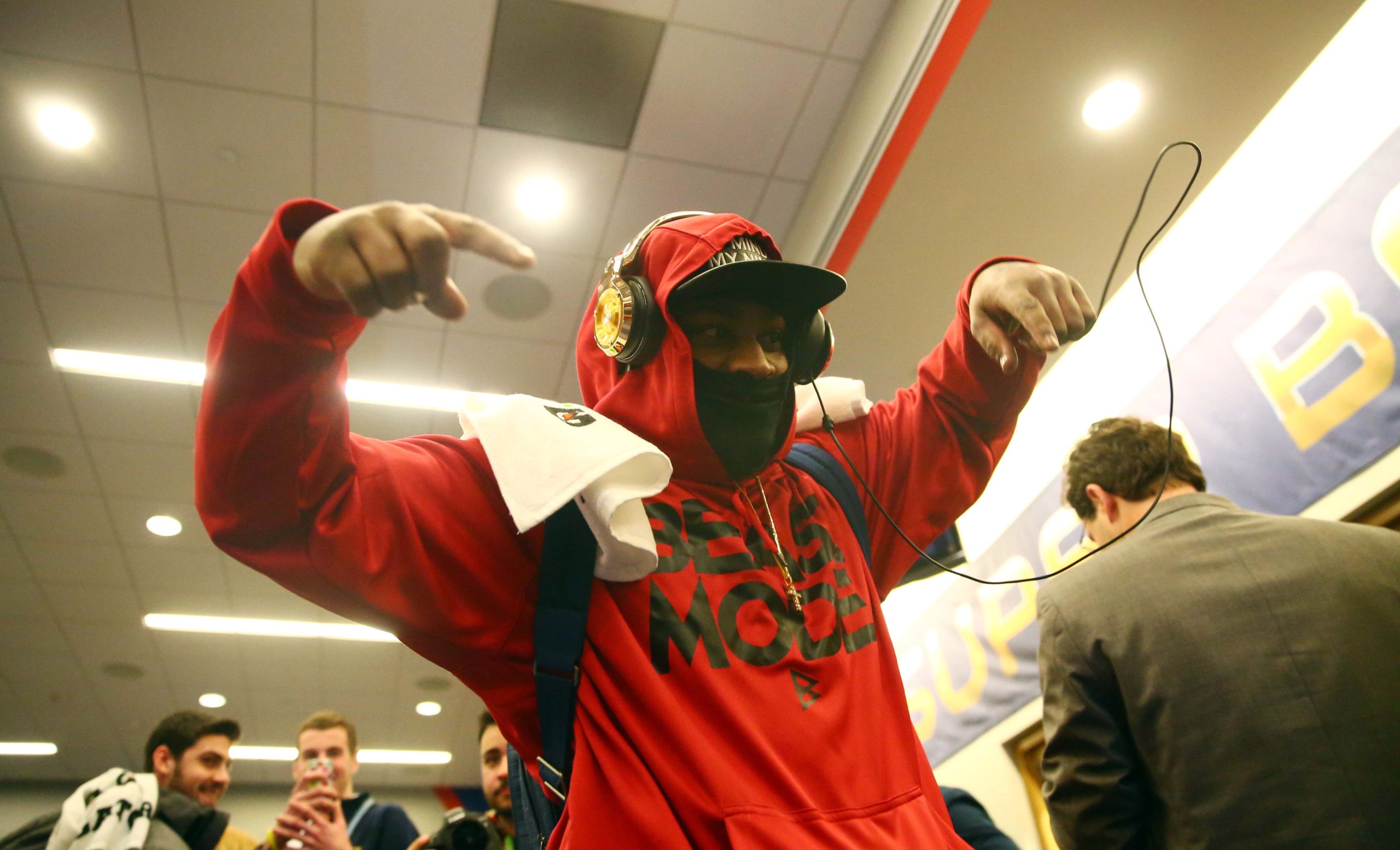

The week after the Super Bowl, my greatest joys, my favorite moments, came from watching the videos of Seahawks celebrating afterwards. Seattle fans felt personal, emotional connections to the individual players in a way I have never seen before in sports. We danced to Bay Area rap with Marshawn Lynch. We screamed at opposing fans with Richard Sherman. We got chills every time Pete Carroll referenced the impeccable connection the players had with “The 12s” in locker room speeches because we knew it was true. I was unable to share my joy with Casey, but I could share it with the team itself – I coped with Casey’s loss by watching and rewatching the Sound F/X videos of Seahawks players mic’d up during the games. I’ve listened to the same song Marshawn listened to in the locker room, Philthy Rich’s Ready to Ride Remix, hundreds of times on repeat. Doing these things created abstract tie points in my life chronology that connect otherwise disparate events – they allowed the joy of winning the Super Bowl to spill over and counteract the sorrow of losing one of my mentors and idols.

Casey’s mantra “It’s not just about sports” never rang truer than during these moments after the game. I was excited that the Seahawks had won the Super Bowl because I wanted to share my happiness with all my friends, with the Seahawks players, with all my fellow Seahawks supporters, and with everyone who knew the joy that a Super Bowl win would bring Seattle fans. Sports do have true value. It’s not just about sports – it’s about the people who share your experiences with, the community of fans, players and sports lovers around you, and there is nothing greater than that.