The Mathematical Pattern At the Heart of Black History

Fractals show up in African villages and hair braids. Do they also also describe a distinctly Black political tradition?

Back to Black: Black Radicalism for the 21st Century | by Kehinde Andrews | Bloomsbury Publishing, 2018

In the 1980s, the ethnomathmatician Ron Eglash was studying aerial photos of a tribe in Tanzania and saw a peculiar pattern governing the distribution of the people’s homes. The area around the village was surrounded by built circular shapes, encircling more circles in an expanding pattern. Eglash’s team spent the decade tracking these shapes across Black Africa. What he and his team encountered were geometric patterns known as fractals.

Fractals are patterns that are infinitely repeating, even at smaller scales. Think of the branches of trees, and how each smaller branch is a similar shape to its larger branch. On a larger scale, clumps of dark matter, called “halos,” (which host galaxies and their clusters) have fractal-like properties. Each clump of dark matter holds smaller sub-structures of dark matter.

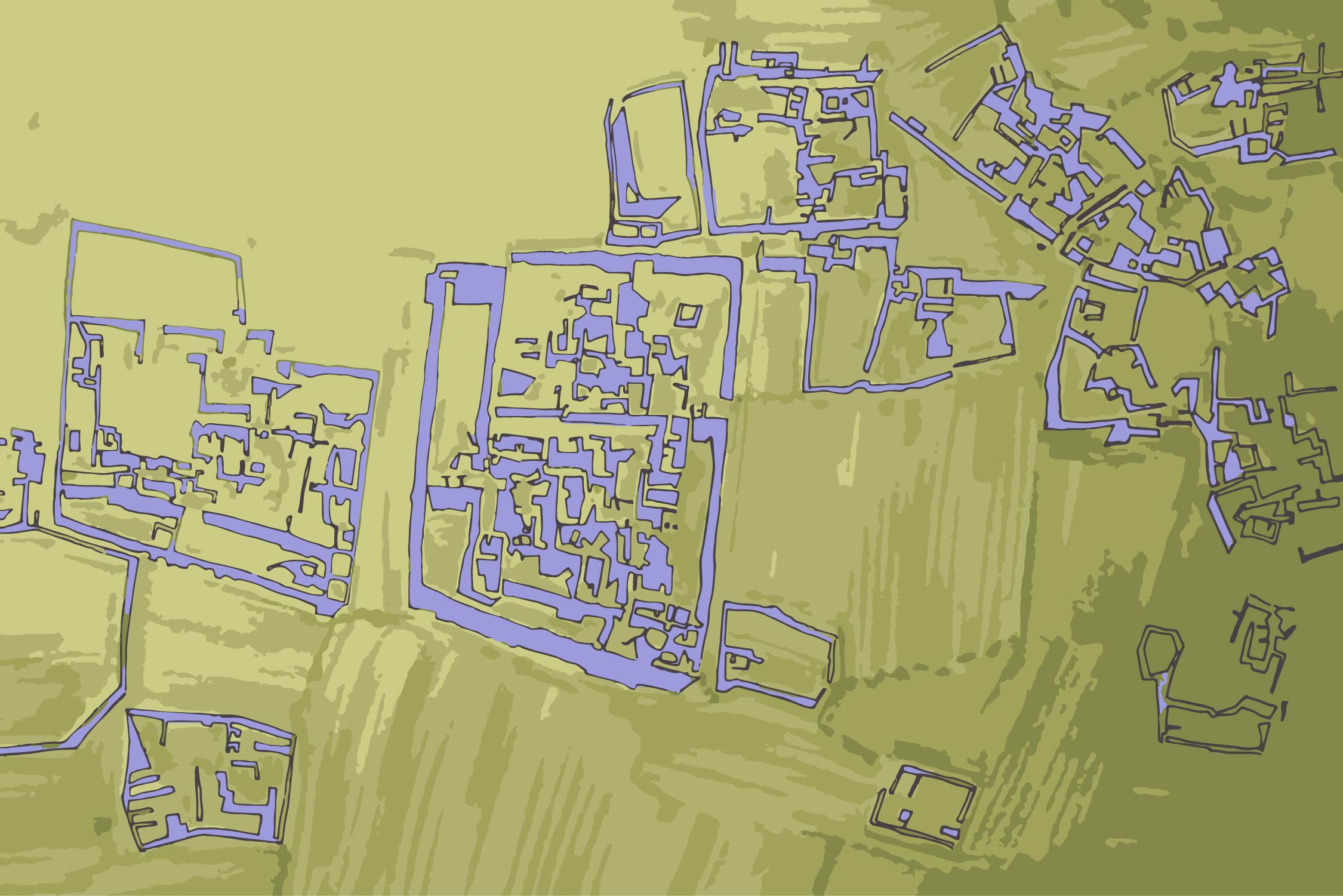

The Kotoko people built the city of Logone-Birni in Cameroon centuries ago using fractal design. They used clay to create self-similar rectangular complexes, added onto each other. According to Eglash, these patterns enacted Kotokos’ patrilocal households. Kotoko men would have their sons build houses next to theirs for security from common northern invasions. Defensive walls guarded the son’s house—a pattern that emerged over the city. “The fractal structures of traditional African settlements,” Eglash wrote, “reveal indigenous knowledge systems that have valuable insights for complexity.”

Beyond urban design, fractals stand as part of Africa’s cultural history. Black people have for millennia, for example, used fractal braiding traditions, enacting intricate math on the contours of the head.

If fractals embody an indigenous African knowledge system, can fractals also embody a distinctly Black political tradition? Kehinde Andrews might have considered such a question in Back to Black: Black Radicalism for the 21st Century. The book scours Black political history to parse varying definitions of the word “radical” as they have been forged by Black intellectuals, from Marcus Garvey to Cornel West, who sought alternatives to the political and economic systems around them.

Andrews argues Black struggles of today must connect with Black freedom moments of the past. “In doing so,” he writes, “we should stop thinking about Black radicalism as a tradition and start to understand it as its political ideology.” Radicalism, he says, rejects the fundamental principles that govern society and creates a new paradigm.

On TV, however, the word “radical” often shows up to label someone with beliefs different from the generally agreed-upon narrative. Think of how U.S. political figures talk about “radical leftists” or “radical Islam.” The use of the term in these contexts is synonymous with extremism and is marshalled to demonize another side.

The mainstream misusage reflects, in part, the term’s slippery history. Without a clear political meaning, “radicalism” will remain a mainstream term of condemnation—rather than the political project Andrews and many others have sought to enact.

The term radical came from the radish, a root vegetable popular in Europe. It also has a mathematical etymology. The mathematical term is a symbol for the root of a number, for example, a square root or cube root; the term is also synonymous with the root itself. Rather than, say, doubling a number, a radical splits it down to its root.

Andrews sees the word as a synonym of “revolutionary.” “So the term ‘radical Islam,’” he writes, “is completely nonsensical.”

Yet is everything that is radical, revolutionary? In mathematics, a revolution refers to a full rotation or a complete 360-degree turn. It is a term used to describe the concept of rotating an object or a function around an axis to create a three-dimensional shape or surface. The object starts and ends in the same position after completing a full revolution.

In politics, a revolution is a significant and often abrupt change in a country or region’s political system or power structure. It involves the forcible removal of an existing power structure and the implementation of a new one.

The mathematical definition taps more closely to the nature of a revolutions as they often take place in practice—starting in one place, ending there too. Take, say, the French or Egyptian revolutions, which deposed their dictatorial leaders and replaced them with other dictators: From Louis XV to Napoleon, Mubarak to el-Sisi.

Revolutions can, however, have a radical aspect in which an alternative is forged. The Haitian revolution, for example, transformed a slave economy into a republic. Just as a mathematical radical stands in for a root number, a political radical should analyze the historical roots of a current system—and consider alternatives on that basis.

Published in 2018, Back to Black revisits various approaches to political-economic thinking by Black visionaries over the past century. Giving broad historical accounts of modern political movements centered around the Black diaspora in the U.S. & U.K. primarily. Andrews delves into both liberal and leftist critiques of the current global order and the alternatives that sprang from such criticisms.

Back to Black is a remarkable account of modern Black thought. But Andrews’ book suffers from a Eurocentric view of Africa. He fails to see the anthropological and historical connections between the diaspora and all Africans, including those regions unrelated to the Atlantic slave trade.

“It (blood) is our direct link back to the continent of Africa, the permanent reminder of a shared connection,” Andrews writes. “Blood takes on such importance because due to the horrors of slavery and cultural genocide, we have nothing else connecting us.”

Africa is the most genetically diverse continent on the planet. If anything, it is our blood that divides us. What connects all Black people are centuries of culture, the kink in our hair, and fractals in our follicles.

Andrews spends much of his book highlighting how certain Black political projects fail to be properly radical. He sees in Black nationalism, for example, the impulse to create a nation per European political ideas. “Narrow forms of nationalism across the Diaspora and on the African continent,” he writes, “present some of the most short-sighted and dangerous politics that promise to further embed Black people in the global system of racial oppression.”

He cites Jamaica, whose economy he describes as entirely controlled from the outside, as a perfect example of the failure of Black nationalism. Andrews points out that for all the political success of Jamaica’s decolonization efforts, the nation’s economy is still wholly dependent on foreign ones. Its narrow self-interest compels it to compete with neighbors, like the Bahamas, for the same pool of foreign tourists, rather than work cooperatively for economic self-reliance. How, Andrews asks skeptically, can a nation whose economy is controlled by others be free?

Andrews also has little time for cultural projects like Pan-Africanism—a cultural movement spurned on by W.E.B. Dubois to modernize Africa “in the framework of imperialism,” as Andrews puts it. A prominent socialist, Dubois advocated for decolonization and African unity from a top-down approach. Like many socialists of his time, Dubois insisted that Africa would be freed “by the most exceptional of us.” According to Andrews, Dubois’ Pan-Africanism is not radical because it relies on the powerful to make radical change. Andrews cautions readers that elitists like Dubois give too little agency to everyday people, preferring to rely on highly educated circles of Black leaders who, as Andrews puts it, “want to be white.”

Andrews’ chapter on Black Marxism is friendlier to its historical figures, as he borrows much of his own politics directly from those Huey Newton and his associates. The core argument of Black Marxism is that capitalism and white supremacy are not just interrelated, but inseparable. While most other Marxists would agree to some extent with this statement, Black Marxists are especially concerned with systems of racial oppression such as the prison-industrial complex.

Still, for Andrews Black Marxists are politically homeless—and set on Marxism simply because it is another political tradition aimed at “raging against the machine,” despite a disconnect from Black political roots that he believes also undermine the radical potential of Black nationalism and Pan-Africanism.

Like many, Andrews sees a lost potential in the sixties, when Newton’ Black Panthers fought for Black autonomy, solidarity, and independence. Yet he does not say what about these impulses had specifically radical potential. In this way, his book offers a broad and generic analysis of the meaning and future of Black radicalism.

Andrews might have found his radical project in the cultural tradition of fractals, which, according to Eglash’s seminal work, African Fractals: Modern Computation and Indigenous Design, have rare ubiquity in Africa. Eglash doesn’t characterize any particular system as “bad or good,” and declines to project political meaning onto mathematical concepts. “We find that there is no evidence that geometric form has any inherent social meaning,” he writes.

Yet in showing, for example, how Euclidean zoning shaped European colonial projects, Eglash demonstrates the polical power and potential of mathmatics as a cultural tradition.

The 16th-century Edo Empire, in present-day Nigeria, cordoned off sections of the city with many radial streets splitting from major streets like tree branches. Fractal city design split the city into guild districts that worked independently, but collaboratively to produce works of art, tools, and other implements of civic vitality. The guilds in Edo demonstrated uncommon skill; they were behind the world-famous Benin Bronzes.

Four hundred years later, the Black Panthers in California would arrange their political group as independent but cooperative chapters from city to city. Like the guilds of Edo, each group would self-organize to solve their issues but come together for problems that required broader collaboration. Rooted in a history of fractals, Black culture flows through this narrative shape—and I can think of no better place from which to start creating an authentic Black political ideology. ▩