The Search for the Giant Palouse Earthworm

Extinction had its logic: This seemed to be a creature of the prairie—and the prairie was mostly gone.

It begins at the interface of glacier and granite: the ice deep and heavy and grinding, the rock gritty, wrecked, and decomposing. There is flowing water, curing sun. A wind swirls from the north, the west, throwing silt to the air and carrying it for hundreds of miles. Ten feet, 50 feet, in some places the earth receives more than 200 feet of fresh sediment. Finer than sand, but not quite so fine as clay, the soil will one day remind one species of kitchen flour. This is a land that grows bread and savors water. Settlers will call it the Palouse.

A soggy forest, an ice age, and then a burst of life: swaths of green and scatters of flowers. There is prairie junegrass and bluebunch wheatgrass, Idaho fescue, wild rose, snowberry, and smaller blooms, too: prairie smoke, sticky geranium, and meadow death-camas. Everywhere there are hawks, hummingbirds, elk, deer, badgers, gophers, and voles. And the soil, the soil swarms with too many creatures to name. Season upon season, bands of people—the Nez Perces, the Coeur d’Alenes, the Spokanes, and the Cayuses—make this land their home.

But when I first came to the Palouse last fall, I encountered a different landscape entirely, one bleached of blooming colors and pared of its once-abundant variety. What I saw, mostly, were fields of lentil and fields of wheat: the brash straightforwardness of industrial agriculture. It took a couple million years for natural forces to form this prairie, and only a century and a half for European-style farming to destroy it. Today, 99 percent of the Palouse Prairie has been plowed for modern uses. The land has sunk six feet since settlers came. It has lost enough soil to uncover a coffin, or to uproot a worm.

The Pacific Northwest has bigfoot, the Scottish Highlands have Nessie, and the Palouse, I soon learned, has the giant Palouse earthworm (GPE). I first encountered the giant Palouse earthworm as the name of a local heavy metal band. I thought it was a joke, but when I searched for the GPE online, I found something real: an elusive white worm rumored to grow up to three feet in length. Over the years, the press had given it a heap of extravagant nicknames, including “Moby Worm,” “Bigslime,” “the Palouse Monster,” “the spineless subterranean Bigfoot,” and the “Holy Grail of earthworms.” Even though nobody had seen one in years—and some count the species extinct—I wanted to believe everything I read about the giant Palouse earthworm. It’s reportedly a fast digger and as girthy as a finger. Some say it smells like lilies when it’s scared. It was, and continues to be, exceedingly rare, often disappearing for decades between sightings. All around my new home, I saw the story of a native prairie in demise, and yet in the GPE I glimpsed different kind of tale, one that suggested a squirmy sort of perseverance, a resistance both to being fully extirpated and fully known.

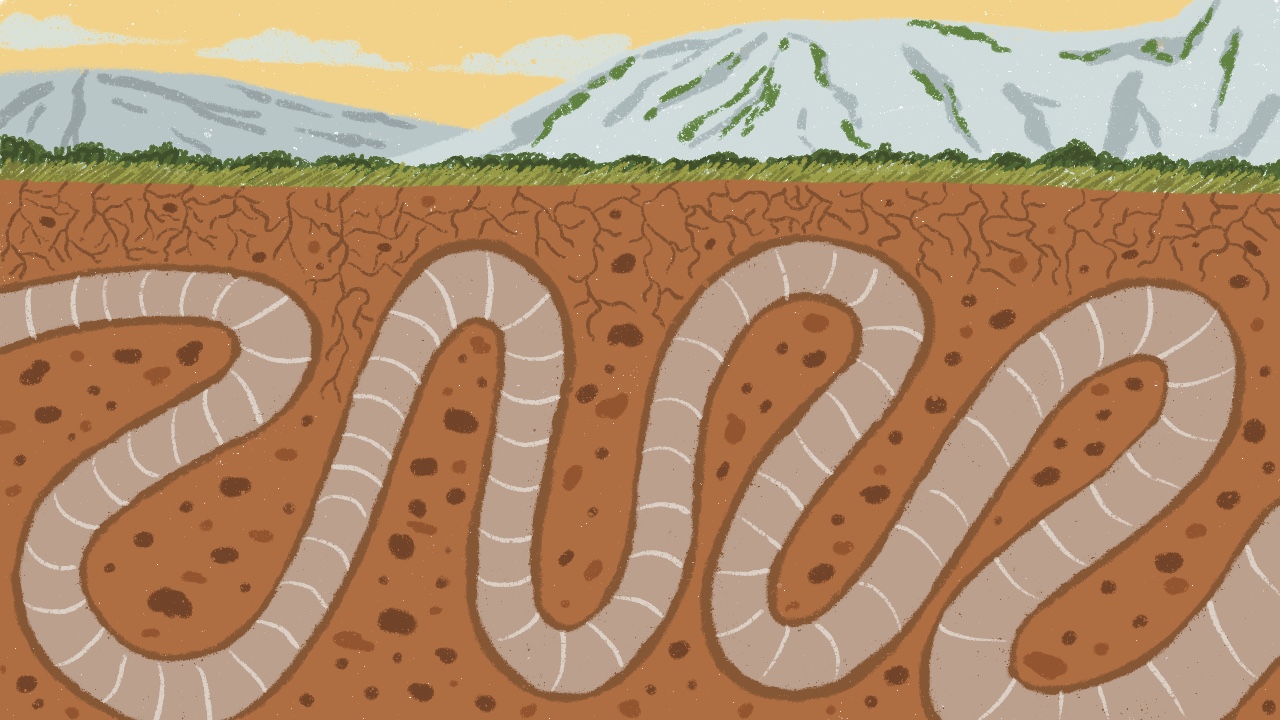

An earthworm body composes itself in segments, each lined with bristles called setae. To dig, a worm coordinates a series of frictions, contractions, and propulsions. Thrusting its rear setae into the soil, it clenches the segments just behind its mouth and pushes its front-end forward, grasping at new ground before repeating the action all along its length. For the earthworm, the path ahead thrusts forth from the body behind. It finds its way in questing pulses and trusts it’s headed in the right direction, even while digging blind.

The first recorded sighting of the GPE occurred in 1896. Rennie Wilbur Doane, a zoologist from the Washington Agricultural College, found an uncommonly long worm hanging out from a road cut in the Palouse. Unlike most worms, this one was pale—white in some places and translucent in others. He sounded the depth of its burrow at an exceptional 15 feet, and noted that, when threatened, the worm discharged a defensive spit that smelled like lilies. Intrigued, he captured several specimens, which he preserved in a vial and sent, along with a letter, to the earthworm expert Frank Smith at the University of Illinois.

Smith believed that the specimens must have been ancestors of Megascolides australis, an Australian species of worm that sometimes grows to ten feet in length. In an 1897 entry to American Naturalist, Smith offers a preliminary technical description of Doane’s worm. He distinguishes the species from North American worms by several internal characteristics, and also by the extent of its clitellum, the ring-like reproductive organ that swells beneath the head of all adult worms. Nearly 40 years later, Smith received a few additional worm specimens from an undocumented source and used them to publish a more detailed taxonomy. Upon retirement, he allegedly donated this collection to the Smithsonian, but the institution today cannot confirm where, or whether, the worms are stored in their building. For all we know, they may have wriggled back underground.

What else can we say of the early encounters between scientists and these befuddling worms? The body of the story is missing segments. Worms do not leave behind skeletons or lasting structures. They do not keep records, nor do they communicate in any language we can understand. Save for the specimens sent to Smith, nearly 80 years passed between Doane’s first find and the next. By that point, the few who knew about the giant Palouse earthworm had begun to assume it had gone extinct, and there was a certain logic to that assumption: If the giant Palouse earthworm was a creature of the prairie, and the prairie had mostly vanished, then it followed that the worm had, too.

The next few times the giant Palouse earthworm surfaced, it did so in places nobody would have predicted. In the 1970s, William Fender, a leading expert on Northwest worms, found some near the Columbia River, on the southern border of the Palouse. Not long after, he happened upon several more in the foothills of the North Cascades, far west of the worms’ expected range. A decade later, an entomologist working in a forest near Moscow, Idaho, discovered a pile of giant Palouse earthworms under a sheet of moss. Each new find demonstrated that the worms were more widespread than anyone had imagined. Maybe they weren’t dependent on prairie habitat after all. Even so, the GPE did not become any easier to find. Again, it went underground and disappeared from the record. Again, people began to count it as extinct.

About 20 years later, in 2005, Yaniria Sanchez-de Leon, a graduate student from the University of Idaho, was doing soil research a few miles northwest of Pullman, Washington. While digging, she surprised herself by chopping a giant Palouse earthworm in half with her trowel. Immediately, she knew that the worm before her was unusual. It was long, pale, and wide as her pinky. She collected both pieces of the body in a vial of formalin and brought them to an expert, who verified the find.

Those who believed the giant Palouse earthworm extinct now wondered whether it might instead be endangered. Hoping to save the worm and preserve what was left of the native prairie, local conservationists petitioned the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service to protect the giant Palouse earthworm under the Endangered Species Act. The agency gathered everything then known about the worm, but could not muster enough evidence to justify its listing. Federal researchers could not establish the worm’s exact range, nor could they identify with any certainty its preferred habitat. Furthermore, the agency had no sense of how many worms remained. For all anyone knew, the worms could have been hiding out in every backyard garden—or holding strong only in undeveloped lands. As one researcher noted, the worms were hard to search for, and finding one often meant inadvertently killing it.

Once I left the University of Idaho archives and reviewed my notes, I realized that, when it comes to the giant Palouse earthworm, most of what we know can only be expressed in negative terms. We do not know what conditions the worm needs to live, or what it eats, or the depth it burrows. We do not know how or when it got here—or even where “here” is.

When we do find the worm, it is often not where we expect it. We believe that the GPE lives entirely, or mostly, below the surface of the soil, but even of that we’re not totally sure. We don’t know what eats it, but we suspect that a lot of things do.

Mostly, we recognize the giant Palouse earthworm by its appearance, and even then only a few scientists have the anatomical knowledge required to identify it with any certainty. Nearly every article written about the GPE claims that it can grow up to three feet in length, but no scientist has ever described one that big. In Moscow, local enthusiasts have brought university ecologists small snakes, leeches, and even photos of mammal intestines, hoping that they’ve found the legendary worm. Most of the time, they haven’t. They’ve only brought their devotion to its myth.

A study published in 2008 surveyed worm populations in Palouse prairie remnants and other grassy bits of conservation land. It found that a single European species, Aporrectodea trapezoides (the purple-red wriggler familiar to fish hooks and most every garden), “completely dominated” both. In fact, the researchers collected but a single giant Palouse earthworm, and it was the only native worm species they found. Still, even if scientific means haven’t succeeded in digging up the GPE, the worm lives all the more vibrantly in myth and in legend; as a species, its spare persistence enchants the land with a glimmer of the prairie’s past. When I look out my window, I want to believe that something big and old could resurface there. I want to believe that enough remains for us to grow a future more varied than monocrop.

In 2016, Chris Baugher, a University of Idaho Ph.D. candidate who devoted much of his graduate work to the giant Palouse earthworm, gave a talk at a community center in Moscow. The most promising method for finding the worm, he argued, was by DNA analysis, which could one day identify the species from the glimmer of slime its body tracks along the soil, or from the fertile balls of excrement, called castings, that it drops in its wake. The best way to uncover the giant Palouse earthworm, he suggested, didn’t require any digging at all. Instead, scientists could learn to read the furled castings or glistening traces its leaves on the soil’s surface.

I listened to a recorded version of Baugher’s talk several months after he gave it. Once his lecture ends, the tape continues, capturing the community discussion that followed. At the end of the recording, Cass Davis, a local worm hunter with an unmatched history of GPE finds, takes the mic. His voice is alive and swelling and almost preacherly in its sense of purpose. Immediately, I recognize in him the same energy that the worm excites in me. Davis declares that he believes the species can still be saved. Although he has never smelled the lily smell, he continues, he has more than once caught something sweet on the air while searching for the worm along nearby Paradise Ridge. Probably, he says, it’s the scent of trilliums, but he’d prefer to imagine something more magical: the spells cast by a mama giant, half the size of the ridge itself. And he’s just finding the babies. ▩